Paul Ryan, the celebrated Republican idea man, delivered a speech today entitled “Restoring the Promise of Upward Mobility in America’s Economy.” Upward mobility is a vital concept for Ryan. He is the author of a plan that would, as budget expert Robert Greenstein put it, “produce the largest redistribution of income from the bottom to the top in modern U.S. history.” Upward mobility is Ryan’s constant answer to this objection. In his telling, his plans would make the economy more open and free, making it easier for the poor to rise and the rich to fall. As Ryan says, “We believe that Americans are better off in a dynamic, free enterprise-based economy that fosters economic growth, opportunity, and upward mobility instead of a stagnant, government-directed economy that stifles job creation and fosters government dependency.”

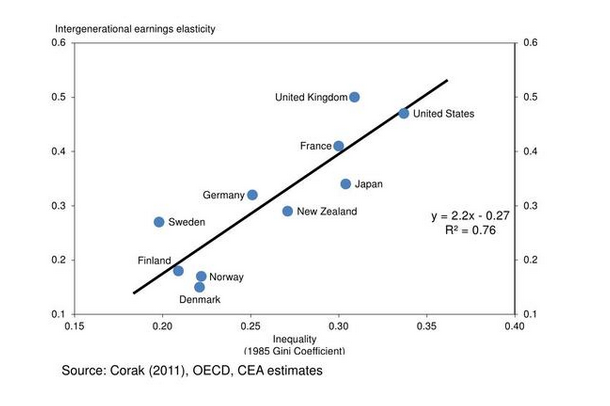

Ryan assumes that increasing the role of the market and decreasing the role of government will increase upward mobility — the wealthier people can get, the easier it will be to get wealthy or to fall out of wealth. But he doesn’t argue it explicitly, and for good reason: There’s no reason to believe it. In fact, the evidence all suggests exactly the opposite. Economic mobility is higher in countries with higher levels of equality and lower in countries with lower equality. The correlation is very tight:

Ryan tells a story in which, over the last several decades, the United States has seen lower levels of economic mobility because government has grown too large. But higher inequality and lower mobility have been growing in tandem.

So, what does Ryan have to offer in defense of his promise to “restore upward mobility”? He offers a riff about the importance of education reform, without either explaining what such a policy would entail or how it would differ from the very aggressive education reforms the Obama administration has implemented. He praises the role of private charity, suggesting that rolling back government assistance for the poor will encourage the private sector to step in, a decidedly shaky proposition.

Mostly, he talks about welfare reform. There is a consensus that welfare as we knew it did create serious cultural pathologies. Ryan cites the case of welfare reform frequently. To him, it proves that large cuts to programs that help poor people of any kind at all are not only harmless but will help the poor. “The welfare-reform mindset hasn’t been applied with equal vigor across the spectrum of anti-poverty programs,” he says. Thus he proposes enormous cuts — to children’s health-insurance grants, Head Start, food stamps, and, especially, Medicaid, which would have to throw about half its current beneficiaries off their coverage under his proposal.

Ryan paints a picture in which we face an impending debt crisis but also have the good fortune of spending vast sums on poor people in a way that harms them, allowing us to reap large budgetary savings while giving the poor a helping hand. What an incredible stroke of good fortune!

But is it true that these programs foster dependency? Ryan avoids fleshing out this implication with any specifics, perhaps because to do so would quickly expose the vapidity of his claims. For one thing, welfare reform was undertaken during the nineties boom, when a red-hot employment market made it possible for people to transition from welfare to low-rung jobs. The notion that there are jobs today going unfilled but for the laziness of the poor has no relationship to reality.

Second, welfare was designed to replace the role of a male breadwinner and thus created a family model in which a single mother could expect to receive a basic income in lieu of work. That isn’t true of the programs Ryan wants to slash.

There is one ironic exception here, though: Medicaid. Medicaid offers health care for the very poor, along with nursing-home care and other special medical needs. It is possible that the availability of Medicaid could reduce a person’s incentive to earn more money, because at some point, they would earn enough to no longer qualify for Medicaid and then they’d lose their health insurance. But this would only hold true if we enact Ryan’s proposal to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Otherwise, people will have access to health insurance at every income level.

Ryan likewise argues that “Medicaid is reaching a breaking point.” It’s true that the cost of Medicaid has risen. But it’s both far cheaper than private insurance and has grown at a much slower rate. Medicaid has gotten more expensive because health care has gotten more expensive.

For all his self-proclaimed wonkery, Ryan does not engage with any of the details of the policy here. All he offers is a hand-waving cover designed to justify the infliction of catastrophic harm upon the poorest and sickest among us. What’s the word for that? Oh, right — brave.