Jessica Grose has an interesting piece for The New Republic observing — and also decrying — that husbands may be catching up with childcare and even cooking, but still do way less housework than women. (“When it comes to housecleaning,” she writes, “my basically modern, egalitarian marriage starts looking more like the backdrop to an Updike short story.”)

Grose casts around for explanations, but does not consider a possibility that probably explains a big part of the gap: Women in general just have higher standards of cleanliness than men do. People who care a lot about neater homes spend more time cleaning them because that makes them happy. And while I agree in general that domestic life requires more gender equality, the housework problem has a partial solution that’s simpler and more elegant: Do less of it.

Viewing housework inequality as entirely a phenomenon of exploitative men free-riding off of female domestic labor makes sense only if you think men derive equal enjoyment from a cleaner and neater home. If that were the case, men who lived by themselves, or with other men, would have to keep their own homes tidy until they could conscript a wife or girlfriend to do their cleaning.

Does anybody think that’s true? In college, I lived in a group house with newspapers for carpeting and pizza boxes stacked to the ceiling. My brother’s three-dude college apartment was so filthy it was condemned by the Ann Arbor board of health. It had a spilled milkshake on the floor that stayed there all year, forming a permanent, unearthly silver blob that became an object of curiosity. (To be clear, this was my brother, not me — I was content with the pizza box tower, but if it was my floor, I’d have cleaned up the milkshake.) My post-college group house was vastly neater than my college home, yet still messy enough that my girlfriend refused to set foot in it, insisting we spend all our domestic time at her place.

We’re now married, which seems like the proper place to note that the mental image you have probably formed of my domestic habits is not accurate. Mainly because I work at home, and her in the office, I handle more than half the parental responsibilities. I buy all the groceries, cook dinner every night, get the kids ready for school, and walk them in the morning. We split bedtime. If one of them gets sick, my wife still heads to work, and it’s up to me to take care of them.

When the kids were born, we got a housekeeper once a week. Obviously, that’s a luxury many people can’t afford. I mention it because, when Grose bemoans “the drudgery of vacuuming day in and day out,” I think, Really? Day in and day out? We pretty much figure the weekly vacuuming we pay for takes care of our vacuuming needs. The cover of New York, featuring Lisa Miller’s story on feminist housewives, has an image of a mom holding a duster. We don’t dust. Ever.

The assumption of much of the feminist commentary surrounding household chores assumes that there is a correct level of cleanliness in a heterosexual relationship, and that level is determined by the female. I think a little cultural relativism would improve the debate. The tidiness level of a home is a matter of simple preference with no right or wrong (except perhaps when you reach the antagonizing-municipal-authorities extremes of my brother’s pad.) My wife and I happily learned to converge on each other’s level of tidiness. We settled — fairly, I think — on a home that’s neater than I’d prefer to keep it, but less neat than she would. She does a little more housecleaning than I do. But it’s not that much more than the time I spend doing the man-work of trash-clearing, lightbulb-replacing, heavy-object-hauling, and screw-turning.

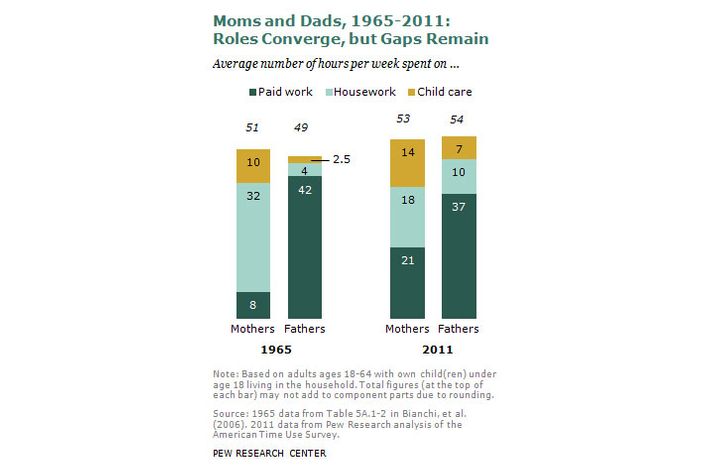

The tricky thing in allocating the responsibilities between partners is that not all “work” can be equated. This neat chart from Pew Research has been making the rounds:

All these things are not the same. Marching the kids through their morning checklist and getting them out the door is stressful work, where every morning feels like I’m trying to pass a bill through the Senate and my kids are Mitch McConnell. Walking them to school is nice. Reading Harry Potter to my daughter, or wrestling on the carpet with my son, is incredibly fun. All those things are “childcare.” Sometimes on weekdays, I have a sick kid on the sofa while I work in the room next door. Look — according to that chart, I performed nine hours of child care and nine hours of paid work! (Okay, eight — we took some story-time breaks.)

Housecleaning is all drudgery and zero fun. But while some of it (like laundry) is necessary, other parts are purely discretionary. I like having magazines strewn across the coffee table. My wife doesn’t. I won’t protest when she stacks them up somewhere, but when she does it, I don’t regard it as her participation in the shared household duties. She handles our household finances, which is a gigantic contribution, out of all proportion to the hours it consumes owing to its stressfulness.

Cooking lies in between, though it depends on the person. I don’t like cooking, especially — if I could magically conjure the meals instead of prepare them, I would. But it does come with the satisfaction of watching your family enjoy the meal, except that sometimes it comes with the frustration of your spouse coming home late and making it cold, or your kid announcing they won’t try it and marching to the pantry to make a peanut-butter sandwich.

A Pew-style chart of my household would show that I do both more paid work and more childcare than my wife — mainly because I don’t commute. But that would present an inaccurately slanted picture of our relative contributions. Having more time around the kids while she slogs through the Red Line is a perk I enjoy, not a cost I’m bearing.

For differing reasons, both feminists and anti-feminists have sandblasted away the distinction between different kinds of work, but the distinction matters. I think Grose’s general point, about the unequal demands faced by women, stands. But the specific indictment about housework doesn’t seem quite as solid.

Feminists want women to work like men do, right? Why not try living like men, too? Put down the duster. It’ll be okay.