In 1990, political scientist Juan Linz wrote what would become a famous essay, “The Perils of Presidentialism.” In it, he noted that presidential systems of government are more likely to incur coups or other crises, and attributed this failure to an underlying tension that can arise whenever the legislature and the president come from different parties: “Who has the stronger claim to speak on behalf of the people: the president or the legislative majority that opposes his policies?” No automatic mechanism exists within the system to resolve this, and so each side has an incentive to escalate its claim and attempt to seize more power.

The incipient showdown in Washington is a form of this underlying tension — not a Latin American–style coup, but very much a crisis of legitimacy. American government has developed customs for resolving the divided government problem. In the best cases, the two parties try to compromise. In the worst cases, failure to compromise leads to stalemate.

Much of the press coverage still presents the disagreement in these terms. Jonathan Weisman reports in today’s New York Times:

For three years, Congressional leaders have relied on tactical maneuvers, sleights of hand and sheer gimmickry to move the nation from one fiscal crisis to the next — with little strategy to deal with the actual problems at hand. Medicare and Social Security continue to swell with an aging population. Health care costs grow. A burdensome tax code remains unchanged, and economic revival is shadowed by the specter of Washington’s crisis-driven mismanagement.

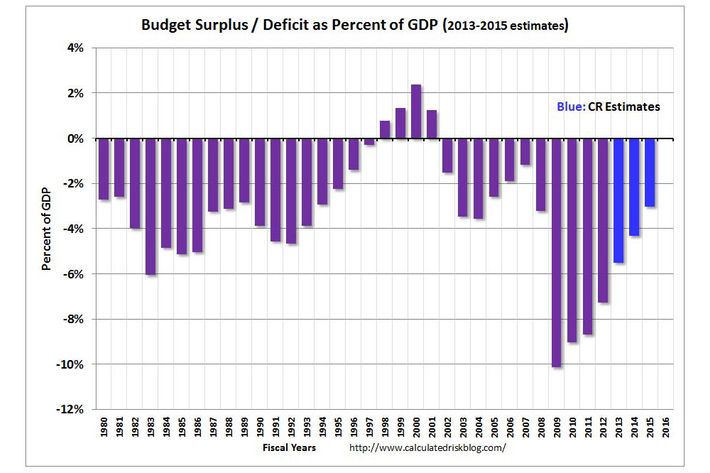

Actually, the budget deficit is falling like a rock:

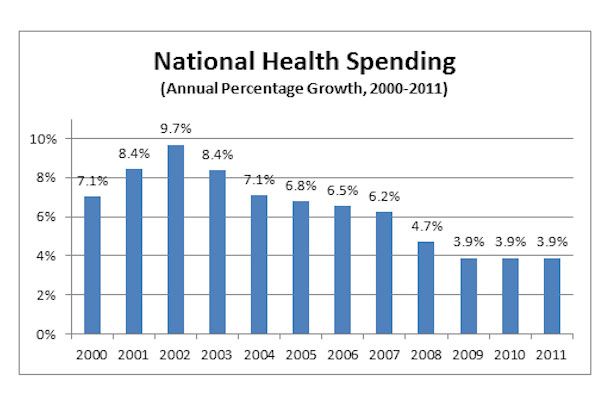

And health-care inflation is likewise falling much faster than expected:

One can make the argument that the long-term deficit picture still looks worrisome. But the long-term deficit is not “the problem at hand.” The problem at hand is that current public policy is exerting a drag on the recovery, and the looming showdowns are threatening to administer more shocks to the system. The problem at hand, in other words, is that we can’t even get to a stalemate.

Since taking control of the House of Representatives in 2011, a coterie of Republicans has challenged this informal approach. Their belief is that the absence of cooperation should lead not to stalemate but to the president bending to their will. That assumption implies a delegitimization of the presidency that Obama has come to understand, belatedly, that he can’t accept.

The Republican Establishment is trying to coax the crisis-mongers out of their fervor. Today The Wall Street Journal editorial page assails Republicans who insist on shutting down the government unless President Obama agrees to destroy his own health-care reform, a fantastical demand. “Kamikaze missions rarely turn out well, least of all for the pilots,” the Journal warns.

But it’s not as if the House leadership has a more reasonable proposal on offer. In fact, the position of the House leadership is far more radical. GOP leaders are promising their base that if they give up on the Obamacare shutdown fight, they can have an Obamacare debt-ceiling fight. House leaders are dangling before the baying hordes, reports Politico, “tons of conservative goodies: construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, entitlement reform and principles for tax reform.” You can have all this and more!

But of course conservatives aren’t sure they can trust their leaders. Last spring, the leadership talked conservatives out of defaulting on the national debt by promising to precipitate a government shutdown in the fall. Now that fall is here, they’re trying to avert the shutdown by dangling a debt default. That threat is actually more dangerous and less credible. As the Journal has argued previously, “Never take a hostage you’re not prepared to shoot.” And Boehner is not prepared to shoot the hostage: He has admitted numerous times publicly, and reportedly in private as well, that he will not allow a debt default.

The tension between the two parties is higher now than ever before because they disagree not only on underlying policy but on the basic premises of shared governance. Obama recognizes that allowing debt-ceiling hostage crises to become enshrined would not only subject him to continuing extortion but set the system on course for an eventual default when, inevitably, ransom negotiations fail at the last minute. Establishment Republicans are trying to talk their base out of extreme measures without addressing their deeper belief that House Republicans are entitled to extract concessions from the president, via threat, without compromising at all.

A source tells Jonathan Cohn that there is no negotiation between the two parties at all: “The breakdown is more extensive than you’ve heard,” this person told me. “There is no discussion going on at all at this point.” When the two parties disagree about whether they should be holding a negotiation with mutual compromises or a process of extortion, there’s nothing to negotiate over. Republicans and Democrats don’t need to resolve their policy disputes to avert a fundamental crisis, but they do need to resolve the legitimacy crisis.