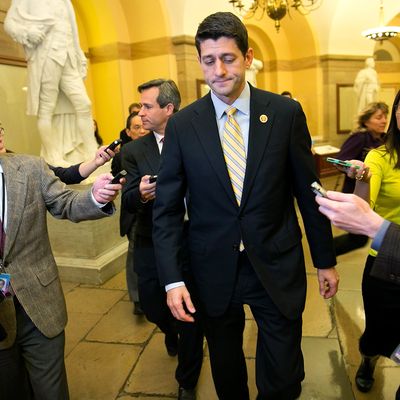

Riding to the rescue, or so it would seem, comes Paul Ryan. Having carefully husbanded his political capital, having escaped the taint of the shutdown by operating exclusively through back channels, Ryan is dusting off his winning persona as earnest fiscally conservative wonk-king. The former veep candidate has taken the lead of the House Republican negotiating position. It is not yet public, but descriptions in news accounts portray Ryan’s plan as mirroring the one he floated in The Wall Street Journal. According to multiple reports, Ryan implored the president to join with him, “telling him that he was missing a historic opportunity.” The Washington Post editorial page cheered Ryan’s proposal (“Obama should embrace it.”) Chris Moody reports, “His strategy in the wake of President Barack Obama’s re-election is to emphasize pragmatic reforms that both parties already support rather than driving initiatives that can never pass in divided government.” The old Ryan narrative is falling back into place.

What Ryan is offering is not in any way a compromise. It’s a ransom payment dressed up in the gloss of bipartisanship.

I should note at the outset that I’m not opposed to long-term deficit reduction, nor do I oppose the possibility of accepting cuts to Social Security and Medicare, if properly designed. The trouble with the deficit scolds is that they overstate both the urgency of making a deal like this as well as its political feasibility. Every deficit bargain that has been designed, inside or outside of Congress, involves a basic trade: Democrats accept cuts to retirement programs, Republicans accept higher revenue on the affluent. Ryan has opposed every one of those bargains. His current plan is very much in keeping with his traditional stance.

Ryan has certainly ratcheted back his most audacious demands. He does not propose destroying Obamacare and does not propose the deep cuts targeting programs for the poorest Americans that are the most noxious feature of his budget. (“This isn’t a grand bargain,” he writes. “For that, we need a complete rethinking of government’s approach to helping the most vulnerable, and a complete rethinking of government’s approach to health care.”) While smaller in ambition, his current plan is equally one-sided.

Ryan is offering to use the cuts that Obama put forward in his compromise budget from last spring. But that budget was explicitly made as a middle-ground offer, and the cuts were contingent upon Republicans agreeing to reduce tax deductions along with them. Ryan isn’t offering any revenue. He’s offering to pocket the concessions, full stop.

In return for this, Ryan’s putative concession to Democrats is that he would lift sequestration, which is automatic cuts to government programs that aren’t entitlements, and replace them with cuts to entitlements. Sequestration was designed in 2011 as a trigger to force the two sides to at some point — likely following the 2012 election — make the budget compromise they couldn’t accept beforehand. It contained blunt, across-the-board cuts to domestic programs, hitting defense most heavily, with the idea that the policy would be so badly designed and disproportionately painful that it would create a mutual incentive to bargain. Ryan’s offer treats the lifting of sequestration as a concession from Republicans to Democrats. In return for this, he demands cuts to retirement programs.

The first is that the Republican stance on sequestration — they love it dearly and would part with it only for a price — is at least in part a bluff. The signs of this bluff are everywhere. Take the appropriations bills, where the abstract cuts to broad categories become translated into actual cuts to programs. How many appropriations bills have Republicans passed? Zero. David Rogers reported last summer that, when forced to impose deep cuts to scientific research and community development, “Senate Republicans are peeling off in protest.”

Republicans have claimed they don’t care about cuts to defense spending — and, indeed, Ryan is putting forward the restoration of those cuts as a concession to Democrats. This is a negotiating ploy. A completely unnoticed piece of internal Republican communication gave the game away here. When House Republicans first released their debt-ceiling ransom list — the Christmas tree, everything-we-ever-wanted list — the note to House Republicans actually conceded the party’s strategy here. It read, near the bottom:

Regarding Sequester fixes: Helping the DOD [Department of Defense] is a priority for us. But the Dems really really really want increase the discretionary caps; it will be their #1 priority in any negotiation. That is part of our leverage.

Why would this be included on a debt-ceiling ransom list? Because many House Republicans are desperate to undo the defense sequestration cuts. The House leaders were telling them, in this list, that they would omit this from their demands because they would get Democrats to offer it for them. (Amazingly, they neglected to strike this confession from the list before leaking it, and reporters were too focused on the demands to notice it.) Ryan’s plan is carrying out the bluff signaled in the party memo — trying to maneuver Democrats into negotiating for something Republicans want.

Likewise, Charles Krauthammer gloats that Ryan’s deal amounts to an unmitigated win for the party: “It’s win-win. A serious attack on the deficit — good. Refiguring sequestration to restore some defense spending and some logic to discretionary spending — also good.” And if the terms of the agreement are all good for one party, and not all good for the other, then it’s not much of a bargain.

There’s a second problem with trading retirement-program cuts for lifting sequestration. Social Security and Medicare are entitlements, meaning their benefit levels are written into law. Taxes are likewise written into law. But the regular government programs affected by sequestration are doled out year by year. Getting a higher spending level in next year’s budget only determines the spending level for next year’s budget. Republicans could just as easily cut the programs they don’t like next year, and Democrats couldn’t stop them.

Richard Kogan, a budget analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, told me over e-mail that House Republicans have not treated agreements on domestic spending levels as binding deals, but have simply gone on to impose progressively deeper cuts:

In retrospect, it is clear that from the beginning the House Republicans as a whole had no intention of funding non-defense appropriations at the levels their leadership had negotiated (or even at the post-sequestration levels) but rather at lower levels. I don’t know if their leadership had informed the Administration during the 2011 negotiations that they intended to provide less than the amounts specified in the Budget Control Act, or if this was a deliberate feint at the time, or if they were pushed to lower levels by their caucus but had otherwise been intending to adhere to the deal.

This doesn’t mean Obama can’t deal with House Republicans. It does mean that if he is going to give away changes in permanent law, he has to win in return changes in permanent law.

The details of the Ryan plan are hazy. Some reports suggest he would lock Obama in to his parameters as a condition of lifting the debt ceiling. That would obviously be unacceptable, a reward for debt-ceiling extortion that would convince Republicans to come back again and again for further ransoms. It would be fine for Obama to agree to unconditional negotiations to lift the debt ceiling. Yet if Ryan’s plan is to win something like the “deal” he has been floating, then Democrats couldn’t possibly accept it. And then, when the short-term postponement of the debt ceiling he’s dangling has expired, we’ll be back to where we started: House Republicans threatening to blow up the world economy unless Obama submits to their will.