What do Twitter, Berkshire Hathaway, and your best friend Dave have in common? Pretty soon, you might be able to buy stock in all three.

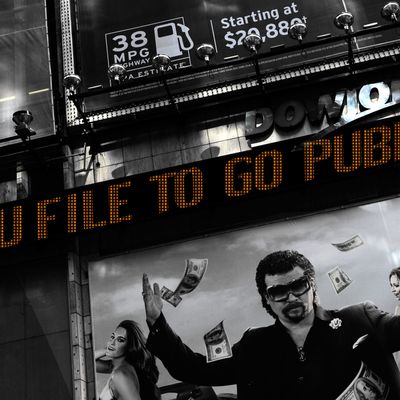

We’ve heard a lot about corporate personhood – the idea that, as one former Massachusetts governor put it, “Corporations are people.” But there’s a new hot concept in the land of personal finance: personal corporatehood, the notion that people can act like corporations. Increasingly, amid record-high stock markets that have rewarded anything with a ticker symbol, normal people are finding new ways to sell stock, lash themselves to investors, and throw themselves at the market’s mercy.

The latest such deal was the IPO of Arian Foster, the NFL running back who partnered with a sports-marketing agency called Fantex to offer himself up on the public markets. Under the terms of the deal, Foster would earn $10 million by selling 20 percent of his future earnings to investors in the form of a personalized “tracking stock.” (The IPO fell through after Foster sustained a season-ending injury.)

But you don’t have to be a millionaire NFL star to play the stock-selling game. There are now a handful of companies offering what are called “human capital contracts” or “income-share arrangements” to normal people. These contracts don’t involve actual stocks, but they have stocklike characteristics. People who sign up for these programs agree to give a percentage of their income to their financial backers for a period of several years, in exchange for a one-time cash infusion. It’s a sort of Kickstarter for people, a crowd-funding platform that provides backers with monthly royalty checks instead of signed T-shirts.

“The whole notion of personal property and domain is changing with the Internet,” Moshe Cohen, a professor of finance and economics at Columbia Business School, told Daily Intelligencer. “There is this trend of becoming commercial property.”

The two biggest of these companies, Upstart and Pave, have funded only 100 or so people between them so far. But the basic idea behind them is spreading rapidly. Federal financial-aid laws already give students an income-based option for paying back their school debts; the legislature of Oregon recently approved a plan that would allow students at state colleges to pledge a percentage of their income in lieu of taking out loans. These schemes aren’t just novelties, supporters say, they’re meant to help young people cope with economic uncertainty by freeing them from mountains of fixed-rate student loans and credit-card debt.

“We didn’t create the economy where long-term safe employment is a thing of the past,” Upstart founder Dave Girouard said in a recent blog comment. “But we’ve designed a financial instrument that mitigates the risk associated with that economy.”

On both Upstart and Pave, applicants are vetted, and offered terms based on what the company’s algorithms determine to be their future earning potential. There’s Jordan, a Wharton MBA graduate who needs money to grow his craft-beer business. There’s Joshua, who wants to expand his necktie start-up. Wealthy investors browse the site, looking for a young person they’d like to support, and offer them some five- or six-figure sum in exchange for a cut of the young person’s future earnings. (Upstart limits investments to 7 percent of a user’s income, and has a ten-year maximum contract length; Pave has five- and ten-year contracts, and caps stakes at 10 percent.)

If you put on your dystopian glasses, it’s easy to see something suspect about the idea of young people in a downtrodden economy pledging away part of their livelihood to the investor class. If Upstart and Pave (and their competitors, like Cumulus Funding and Lumni) succeed, other start-ups could come in with even more onerous terms. Although both companies are said to be in frequent discussions with regulators, there’s nothing illegal about what Upstart and Pave are offering. And in the future, regulators could sign off on these schemes as examples of innovation in personal finance, the JOBS Act could open them up to unaccredited investors, and we could wind up with a society where vast numbers of people are traded like stocks, where every life is assigned a monetary value, and where Wall Street bankers bundle the income streams of a bunch of 22-year-olds into exotic financial instruments.

“These structures seem to be getting more and more popular,” said Stacy Kanter, a partner at the law firm Skadden, Arps. “They’re risky for investors, but they’re also risky for the people who are exchanging some of their freedom for a significant cash payment.”

Filmmaker Clara Aranovich, 27, seems willing to bear that risk. A graduate of Dartmouth and the USC School of Cinematic Arts, Aranovich recently raised $50,000 from a team of backers on Pave in exchange for a ten-year contract entitling the investors to 5 percent of her earnings. She wants to use the money to make her first feature-length film.

“Committing to something for ten years is daunting,” Aranovich said. “But the more I mulled it over, and realized what I could do with $50,000, the benefits definitely outweigh the drawbacks.”

Aranovich compared her deal with her backers — a group that includes a current Goldman Sachs managing director and several other wealthy financers — to the kind of fee-sharing arrangement an actor might make with his agent. She said that even though she was duty bound to write a check to Pave for 5 percent of her income every month for the next decade, “even if I quit film and become a maid,” she wasn’t bothered by the obligation.

“I literally could not have survived in this job had it not been for that Pave money,” she said.

As Aranovich’s situation shows, services like Upstart and Pave thrive in desperate times. In a healthy economy with near-full youth employment and easy access to traditional forms of credit, it’s hard to imagine Ivy League graduates chaining themselves to wealthy patrons via high-tech income-sharing arrangements. But if corporate profits and stock prices keep soaring while the labor market remains depressed, it makes sense that people would want to behave more like companies. And while Upstart tells its backers to expect 8 percent interest on their money, some are probably hoping to make a much bigger return if their human stocks outperform.

“There’s a lot of malaise in people coming out of college right now. I’m not surprised that some investors want to harness those people’s potential,” Aranovich said. “And maybe take advantage of it.”