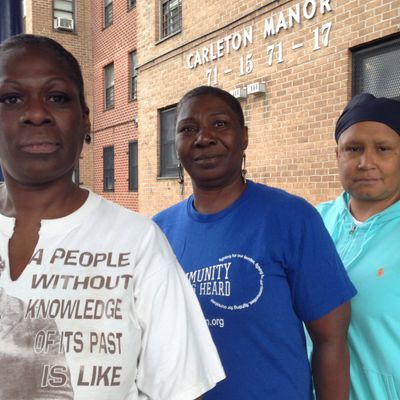

Vernell Robinson was stressed. The 51-year-old resident of the Carleton Manor public housing project in the Rockaways sat last weekend in the putty-colored community room of her building with two other local activists, Danielette Horton and Lawanda Johnson-Gainey, trying to figure out how to inspire a busload’s worth of fellow low-income Rockawayers to join them for the trip into Manhattan on Sunday for the People’s Climate March. Organizers of the march, which will occur in advance of next week’s U.N. Climate Summit, hope that it will be not only one of the biggest environmental rallies in history, but one of the most racially diverse, dispelling forever the climate movement’s reputation — and, at least in its upper echelons, its true history — as a preserve of privileged, outdoorsy white men.

Robinson and a few of her fellow Carleton residents got involved with climate activism after Hurricane Sandy. Sand got into the pipes at Carlton Manor and major storm damage to exterior brick walls remained unrepaired to this day.

“I’ve been a community activist for ten years,” said Robinson, showing off flyers she’d printed up that the trio intended to hand out personally around the neighborhood, telling people that the huge and seemingly abstract issue of climate change was poised to decimate their lives in the years ahead unless citizens demanded action. “But on climate, Sandy was the turning point for me,” she said. “It got very personal for me when we were left in the dark.” (The storm wiped out power in the area that was not restored for weeks.) “And it got very scary. I don’t want my granddaughter growing up with these problems.”

So Robinson, a member of the low-income activist group Community Voices Heard, had pulled $23 from her own pocket to print up flyers about the climate march. “We’re trying to raise awareness and get people to connect the daily stuff to the big picture,” she Robinson. “The energy from the march will have a trickle-down effect.”

Horton, who was born in Liberia and lives in the nearby Hammel Houses, said, “I want people around here to be conscious of the planet.”

Their words would’ve been music to the ears of the organizers of the People’s Climate March, whose very name suggests the desire to expand the movement beyond the stereotype of wonky, well-to-do men with light complexions (think Al Gore, Bill McKibbin, RFK Jr.). They hope the protest, reflects who actually is most at risk from climate change: regular people, often urban and poor and with little mobility — be they residents of the Philippines or Red Hook. This broadened perspective is often called the environmental justice movement.

The moment has been long in coming, says Phil Aroneanu, a co-founder of the climate action group 350.org (and, he’ll sheepishly admit, a white male). “If you look at the Big Green lobby of major environmental groups — including Sierra Club, Greenpeace, National Wildlife Federation — almost all of their executive directors have been white men, with a few white women. Most of the faces at the major climate rallies in recent years — Copenhagen in 2009, D.C. in 2013 — have been white, even though people of color have been doing work on the ground for years on environmental issues that affect their communities.” He cited Gulf Coast activists after Katrina, New Yorkers after Sandy, West Coast Asians fighting a Chevron refinery, Bronx residents (including controversial activist turned corporate-consultant Majora Carter) protesting asthma-causing truck pollution, and Louisianians taking on the state’s notorious “Cancer Alley.”

“But Big Green, and that has included us at 350, has had a huge blind spot in terms of connecting issues of nature and preservation with more urban, everyday environmental issues and bringing those communities into the tent,” he continued. He said that 350 planned this march differently from prior ones, reaching out for co-planning help as early as February to a broad coalition well beyond the usual suspects. Dozens of unions signed on, including two of the giants, SEIU and the American Federation of Teachers, both of which have highly diverse member bases. Getting them onboard was a major coup, as labor has often found itself on the other side of the green movement’s demands. The NAACP and hundreds of community and activist groups like Robinson’s also joined the coalition.

The march will specifically spotlight faces and stories of color, says Iain Keith, a campaign director (and another white male) for Avaaz.org, the slick global activist campaign group that has funded the march’s extensive subway ad campaign. Leading up to the event will be, for example, a super in an energy-efficient NYC building who stayed in it for two weeks ferrying supplies to residents during Sandy; a Native American woman who fights fracking in South Dakota; and Elizabeth Yeampierre, a Latina who is organizing Sunset Park in initiatives including decontaminating the area’s waterfront and creating a park there.

The point is to relentlessly drive home the connection between extreme climate and its effect on everyday urban lives, says Eddie Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, which is involved in the march. “This is about where people live, work, and play — it’s about the ‘hood, the barrio. Most people can get that. Even if you’re fighting against police misconduct, for example, think about what that’ll be like when most of our summer days become over 90 degrees. People are starting to make these connections.”

Organizers are hoping that this new tack will finally stop the flak that Big Green has been taking for years for its lack of diversity. The march comes on the heels of a major report this summer finding that while white women were making gains in environmental leadership positions, the percentage of nonwhites in such roles was merely 12 percent.

The bigger aim is not merely to diversify, though, but to build out — in a big way. Environmentalists are realizing they cannot slow or reverse climate change merely by getting people to change their lightbulbs or boycott plastic bags — they desperately need massive public support on a scale where they can be a force against the fossil-fuel lobby, which is the nation’s largest. “We hear from politicians all the time that they don’t hear much that the public cares about climate change,” says Keith. “We have to open the tent and aim for huge scale with this march, to show that a lot of people are willing to sacrifice a Sunday afternoon to take to the streets.”

Says Aroneanu, “We’re laser-focused on building the kind of movement that’ll get the legislation we need passed. We have to make it huge so politicians can’t ignore it.” (His group is named 350 because, to quote its website, “to preserve a livable planet, scientists tell us we must reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere from its current level of 400 parts per million to below 350 ppm.”)

Organizers say they hope that the march will draw at least 40,000 people, the number who attended a huge, 350-organized march in D.C. in February 2013, and perhaps will exceed 100,000, the estimated number that attended the biggest climate march ever, in Copenhagen in 2009.

Getting the buy-in of the labor powerhouse SEIU, which played a major role in getting de Blasio elected mayor, was a no-brainer for the union, says Lenore Friedlander, who works in SEIU’s 32BJ sector, which represents building maintenance workers. “Our members experienced a wake-up call around Sandy,” she says. “They saw and felt the impact of extreme weather in a very direct way. We had thousands of members whose buildings where they work were closed down because they were underwater. Many of them couldn’t get to work because the city shut down transportation, and some ended up stuck at work. We had cleaners in the public schools, which became evacuation centers, flooded with people looking for a safe place.”

In the Rockaways, Robinson remembers October 2012 all too well. She’s still fighting to get that sand out of her pipes, those holes in her wall fixed, and a nearby playground repaired after Sandy wrecked it.

She sighed, gathering up the flyers she was hoping would help pack that bus to Columbus Circle come Sunday. “A lot of folks out here are so despondent, they don’t want to be bothered with anything,” she said. “But I have to be involved in this march. Before I leave this earth, I want to make sure all my people know what’s going on with this issue.”