This morning, a militant in a white robe and a graying beard, a spokesman for the terror group Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, released a video in which he said that his group was responsible for the Charlie Hebdo attack, having picked the target and the attackers. It’s early, but the analysts quoted in this morning’s news stories mostly said the claim appears credible, particularly since the Kouachi brothers had shouted, while inside the magazine’s offices, that they were there on Al Qaeda’s behalf and since, too, there are reports that Said Kouachi traveled to Yemen in 2011. (Left unresolved is the matter of why AQAP would have waited a week to claim responsibility; perhaps this was a loose affiliation.) This moment — when some organized group claims responsibility — is one of the things we wait for after terror attacks: It offers clarification and suggests what might happen next. But this time the claim, even if we assume it is true, seems to mean less than it used to, and the difference may say something about how individual jihadists are radicalized in the 21st century, and how their stories intertwine with the long history of the war on terror.

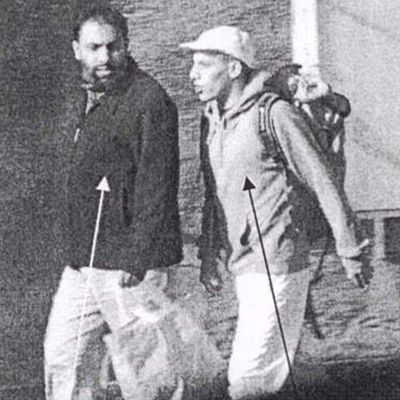

It’s often been said that Sherif and Said Kouachi were “known to French intelligence.” But in some ways their group of friends were, more simply, known to the French. Sherif had been briefly featured in a 2005 French television documentary, as part of a group of jihadists based in Paris’s 19th arrondisement. Timothy Holman has put together a very useful chronology of the movements of this group — maybe 11 active participants among a broader circle, he estimates — over the past decade and a half, culled entirely from French media reports, which is to say that this small group’s long experience as jihadis (the pre-history for the horrifying acts this week) has unfolded in some public form over just about the same length of time as the American war on terror, whose excesses often outraged them and whose movements, at times, they mirrored.

Kouachi’s interest in radical Islam, the Times has reported, was “rooted in his fury over the United States’ invasion of Iraq in 2003, particularly the mistreatment of Muslims held at Abu Ghraib prison.” By March of that year, other members of the group — organized around a janitor and preacher named Farid Benyettou — were already in Iraq: A French radio journalist in Baghdad broadcast one of them shouting out to his “mates in the 19th” — “come and take part in the jihad, it is me, Abu Abdullah, I am here.” There were debates among the members of this group over whether to target Jewish interests within France (eventually they decided not to), and at least four of them made it to Fallujah to fight American troops. In 2005, Benyettou and Cherif Kouachi were arrested and eventually convicted of operating a network designed to funnel foreign fighters to Iraq; they served three years. In 2008, a man linked to Benyettou was arrested while planning an attack against the French interior ministry. In 2010, more than a dozen men linked to Benyettou were arrested while plotting to spring another French terrorist from jail. In 2011, one of the Kouachi brothers traveled to Yemen; the speculation is that he may have been in the company of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. In 2013, Tunisian police announced they were seeking another member of the network in connection with a plot to assassinate an opposition politician there; the next year, he turned up on an American list of the most influential leaders within ISIS.

This is a remarkably profligate set of causes, and affiliations. Perhaps beneath the public history of the Benyettou group (or trajectories; Benyettou himself has apparently become a nurse, and a less active jihadi) there were finely grained ideological debates, and pivots, about which particular wing of Islamic fundamentalism was the most righteous, the most amenable. But this doesn’t look like the City College cafeteria. This looks like a group that would have been amenable to working under the banner of just about any jihadist group, and often did. It’s possible that AQAP had the organizing role in this attack that it claims. But it seems equally plausible that members of the Benyettou group would have carried out attacks of a similar scale even if AQAP had never existed. Certainly we know that, long before AQAP entered picture, they tried.

The imagery of 9/11 is still so strong that we expect that most terror attacks will resemble it, and that terrorists will resemble those who carried it out. For instance, we expect them to be religiously orthodox: On CNN last week, Wolf Blitzer reviewed the news that Cherif Kouachi had smoked marijuana and been videotaped rapping, and concluded that “clearly he’s got a history that’s, let’s say, unusual for someone who’s now being accused of engaging in massive terrorism,” even though terrorists are not usually religious ascetics and these kinds of behaviors are common among them. More important, we often expect to find a large group hidden behind them, organizing logistics and training, picking targets. But often these are not present — consider Nidal Hasan at Fort Hood, and Michael Zehaf-Bebeau in Ottawa, and the Tsarnaev brothers, none of whom were very strongly attached. “The hardest problem,” a former British intelligence officer told the Times this morning, is “what we call ‘target acquisition,’ figuring out who these people are, rather than investigating known targets.”

Figuring out who individual radicals are, of course, is both more difficult and more fraught with civil liberties intrusions. It also confirms a long turn in the fight against terrorism, which may increasingly be fought not through war but politics. For a decade after his initial outrage over Abu Ghraib, Cherif Kouachi moved through Paris — training in parks, contemplating targets and movement, affiliated mostly just with his small group of friends. There are so many people like Kouachi in France — Muslims seduced by the rhetoric of anti-Western jihad that has built over the last decade, and perhaps outraged or politicized by some aspects of the war on terror that we have conducted — that French authorities could not track them all, and at some point, according to French journalists and CNN, started paying less attention to Kouachi himself. It may be that, in trying to figure out “who these people are,” we are no longer at war only with the formal groups of Al Qaeda and its successors, but also with the legacy of the war on terror itself and the individual murderous radicals left in its wake, which is to say with our own history.