How the President’s Longtime Confidant Became His Greatest Adversary on Climate Change

Laurence Tribe is fighting the White House on behalf of Big Coal. His friends are furious at him, which breaks his heart.<br /><br /><br /><br />

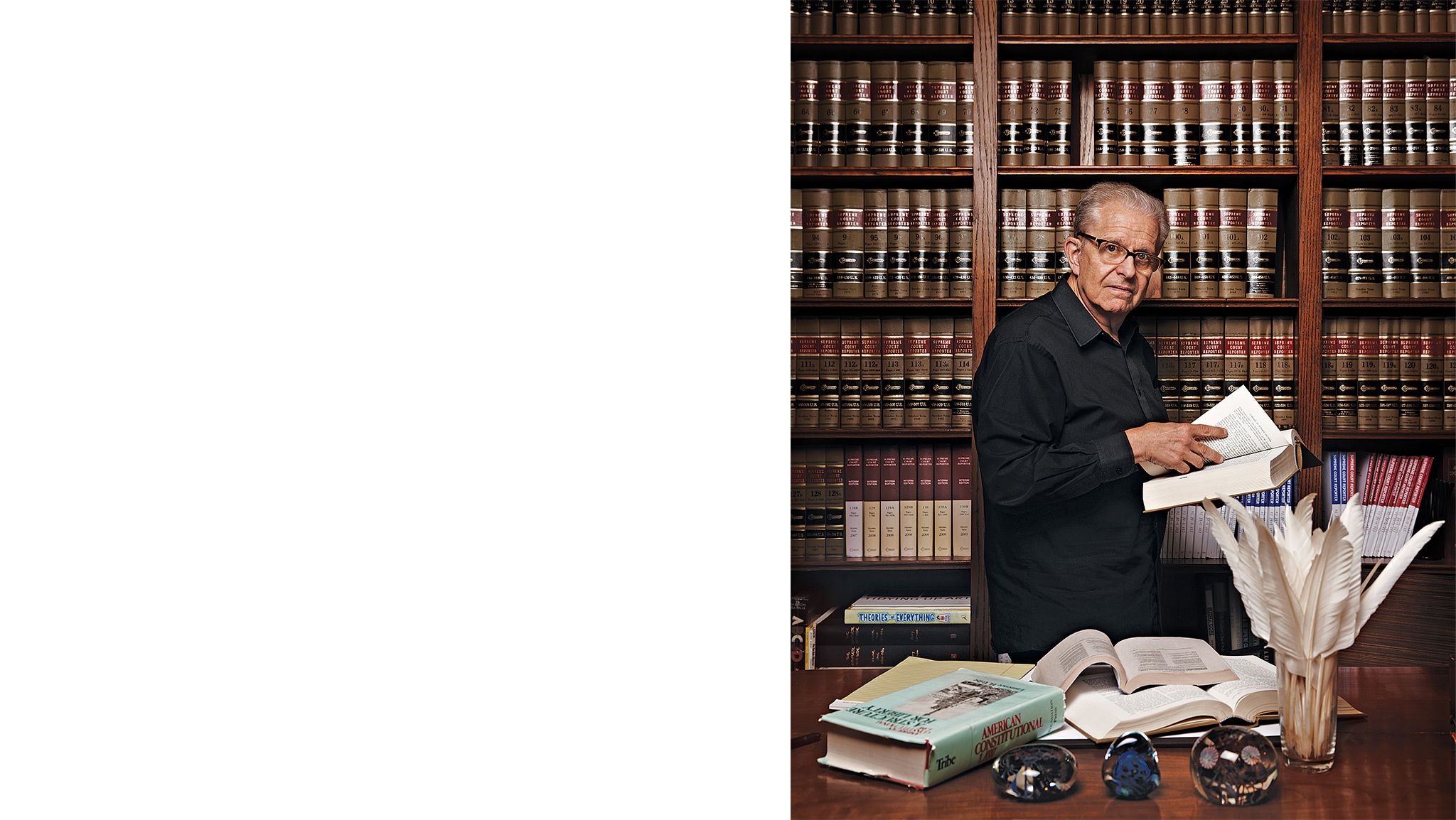

Tribe?

confidant, is fighting the White House

climate plan on behalf of Big Coal. His friends are

furious at him, which breaks his heart.

Just after noon on June 18, Laurence H. Tribe, the nation’s foremost scholar of constitutional law, fired off an angry and anguished self-defense. “I just finished my roughly half-hour interview on WNYC with Brian Lehrer,” he wrote in an email to the publishers of his most recent book about the Supreme Court, Uncertain Justice. “I suppose I did well enough, but the interview was a complete disaster. Please let the Brian Lehrer Show know that I felt totally sandbagged.”

The appearance had begun innocuously, with a discussion of the most recent Supreme Court decisions — what the Harvard Law professor later called June’s “series of thunderclaps.” Tribe’s credentials as a liberal legal activist are the stuff of legend — counsel in Bush v. Gore, slayer of archconservative Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork — and he is as informed about the Court’s opaque inner workings as any outsider can be. He taught Elena Kagan and John Roberts at Harvard and played an unusually involved role in Barack Obama’s education in the law; for a brief time during Obama’s first term, he served at the Justice Department. At 73, Tribe is accustomed to his preeminence. So he bristled when Lehrer courteously but insistently turned the conversation to his other role, as a highly compensated litigator for a coal company fighting Obama’s climate-change initiative.

“Can a scholar take a client like that and maintain an appearance of independence?”

“Well, I’ve been doing this kind of thing for decades,” Tribe replied, the ice creeping into his voice. “And I’m just not for sale.” He had the urge to hang up the phone then and there. But he fought it off and handled another 90 seconds of questioning with superficial aplomb. “I have had a career that I’m proud of. I’ve represented causes that I believe in,” he said. “And whether I believe in the cause or not is not a function of whether the client is corporate or noncorporate.” Inside, though, Tribe was churning. “It was an inexcusable ambush,” he wrote immediately afterward, an “awful caricature.” He was flummoxed that people involved with a friendly NPR show would prove to be “such venomous snakes.”

Tribe’s emotions might seem extreme in light of the tenor of the conversation and the fact that he should have known the questions were inevitable. But the controversy over his role in the climate case had upended his place in the world, setting friends and colleagues against him and shaking two pillars of his reputation: his liberal idealism and his legal brilliance. The reversal dates to last year, when Tribe got involved in a constitutional challenge to Obama’s plan to curtail power-plant carbon emissions. His client, Peabody Energy, is the world’s largest private-sector coal company. The bare facts of the case concern dueling interpretations of an arcane passage of the Clean Air Act, but the political ramifications are monumental. Enemies of the climate initiative, which aims to cut emissions from the power sector by 30 percent from 2005 levels, see it as a naked abuse of executive power intended to put companies like Peabody out of business. Proponents say the new regulations fall well within the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority, and that the coal industry is destroying the planet.

“For most environmental-law scholars, climate change is the challenge of our lifetime, it is an existential threat to life as we know it,” says the UCLA law professor Ann Carlson, who has written that Tribe is “destroying his reputation” as a constitutional theorist. “I think the question is, how can Larry Tribe be attacking the president’s climate-change policy in this way?” Both sides of the carbon-regulation battle recognize that Tribe’s name has currency. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has taken to citing the “iconic left-leaning law professor.” A pair of Harvard environmental-law experts, Jody Freeman and Richard Lazarus, singled out Tribe in a blog post on the university’s own website, attacking his “sweeping assertions of unconstitutionality” as “ridiculous.”

“Were Professor Tribe’s name not attached to them,” they wrote, “no one would take them seriously.” The spectacle of a Harvard-faculty feud, along with reports of “particularly fierce” anger emanating from the administration of Tribe’s former student, served to escalate a dry dispute into political drama. Tribe has been fielding a deluge of emails from old friends and former students. “The ones that really hurt,” Tribe told me, “are from people who, for whatever reason, took me as something of a role model, who are saying: ‘What a disappointment. Why are you selling out to the coal industry? Don’t you care about your grandchildren’s future? You’re helping to ruin the planet, and I’m losing faith in you.’ ” He has poured his lawyerly vehemence into long justifications sometimes punctuated by hopeful emoji:![]()

![]() .

.

In early July, Tribe traveled to the Chautauqua Institution, a lakeside retreat in western New York that hosts a summer cultural festival, to give a lecture on the Supreme Court. “The Constitution is a great teacher,” Tribe told the audience. “It expands our field of vision.” He was especially invigorated by the recent Obergefell v. Hodges decision, which enshrined a constitutional right to marriage. Tribe defended gay rights before the cause was popular and took justifiable pride in the victory. “As I sat at home watching these events unfold,” he said in his speech, “I took out my small copy of the U.S. Constitution. Its words hadn’t changed, but somehow it looked bigger.”

Then one audience member asked Tribe to defend his representation of “corporations in opposing provisions of the Clean Air Act.” Another brought up the Koch brothers. (They are tangentially connected to another Tribe client, an organization fighting a wind-power plant.) “Is there any constitutional basis,” Tribe was asked, “for protecting our democracy and our environment from that kind of corruption?” Tribe dutifully ticked off his defenses. He claims he only makes legal arguments he believes in, that more than half his cases are pro bono, that his quarrels with Obama are limited to this one policy, which he says is an unconstitutional power grab.

Finally, sounding exasperated, he reprised an incendiary line: “As I’ve said — some people said I was being a little melodramatic — I don’t think burning the Constitution instead of coal will really be a way of saving the environment.”

A few months before, on a steamy spring afternoon in Washington, I met Tribe at the Georgetown Ritz-Carlton. That morning, he had argued Peabody’s case before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. He had just awoken from a nap, refreshed after his morning in court and a customary post-argument martini, which he’d consumed over a lunchtime debriefing session with his clients at the Capital Grille. Now, amid a swirl of bankers and dignitaries in town for a global IMF summit, he told me that he bore Obama no ill will and even sympathized with his desire to act as his time in office ran short. “Presidents have very limited power, even as commander-in-chief, and they all realize that, and therefore they champ at the bit,” he said. “I’m sure this climate initiative, at least as much as health care, is part of immortality for him. This is what he can do that can make a huge difference for generations. And I wish him well. I just wish he could find a constitutional way to do it.”

Tribe has spent his career divining the entrails of the Supreme Court’s opinions, parsing the signals it sends via asides and footnotes, and developing an understanding of each justice’s view of the Constitution. He knows all of them personally, apart from Samuel Alito. That deep knowledge, in turn, has made him a fortune as an appellate attorney. Tribe sees no conflict between these roles, only a lucrative symbiosis. Like many liberal constitutional-law scholars, he is intellectually skeptical of the ways in which Obama — himself a liberal constitutional-law scholar — has sought to expand executive power. Some of his peers are dismayed by the president’s assertion of the authority to summarily execute American-born terrorists with drones, his sweeping up of phone data, and his continued detention of prisoners at Guantánamo. Tribe has picked a much more unpopular place to make a stand, but he says that the truth, however unpleasant, is that the Constitution contains rights for coal companies, too.

Tribe has argued 35 cases before the Supreme Court, winning well over half of them, and is frequently hired to handle appeals in lower courts. Once a champion collegiate debater, he relishes the rush of oral arguments. He doesn’t like rehearsing — he eschewed moot courts for years, thinking they would dull his edge of anxiety. Before a case, he often lies awake at night, testing out inventive lines of argument in his head. “His recall and understanding of the relationship between things in constitutional law is almost beyond comprehension,” says Tom Goldstein, publisher of SCOTUSblog, who collaborated on appellate cases with Tribe for years.

Sometimes connections come to him in a flash. One night, shortly before he was to appear before the appeals court on Peabody’s behalf, he thought up an answer to the government’s strongest argument, the contention that it was not yet possible to judge the EPA’s rule because it was not finalized. Sure enough, at the hearing, it took less than a minute for Judge Thomas Griffith to pose the question: “Do you know of any case in which we have halted a proposed rulemaking?” When it came time for Tribe to offer his answer, he reached back four decades to cite U.S. v. Jackson, a decision about guilty pleas and the death penalty, which he had helped to craft as clerk to Justice Potter Stewart.

“One needn’t wait to see if the guillotine drops,” Tribe said.

The metaphor might seem histrionic, but Tribe argues that the mere threat of regulation poses catastrophic risks to the coal industry. The U.S. energy market’s reliance on coal-fired power plants has been shrinking because of cheap natural gas from fracking and pressure from environmental groups. Peabody’s stock price has plunged by 97 percent over the past four years, and many smaller coal companies have gone bankrupt. The industry argues that the new carbon-emissions standards will cause more plants to close, raising rates for consumers and disproportionately harming the more coal-dependent states. In filings on behalf of Peabody, Tribe argues that the EPA’s action is “aimed squarely at stamping out coal.” Environmental advocates say he’s exactly right.

For this reason, the courtroom was packed with energy and environmental lobbyists. Lazarus and Freeman sat side by side in a reserved row, scribbling notes. Everyone involved recognized that this particular lawsuit was a long shot. (Ultimately, the court would end up rejecting it on the narrow grounds of its being premature.) But the antagonists were treating the argument like the first round in a prizefight — a chance to throw a few jabs, probe weaknesses, and test lines of attack. The dispute will almost certainly end up before the Supreme Court, soon. The panel of three Republican-appointed judges sounded unsympathetic to the EPA. They were constrained, however, by a key precedent, derived from Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, which holds that agencies are entitled to deference when it comes to interpreting laws.

“If I saw two absolutely conflicting positions,” Griffith said, “then it is Chevron, right?”

“I would try to look at that decision and read it more narrowly,” Tribe replied, “in order to avoid accusing the Supreme Court of not knowing how to read the Constitution.”

Tribe has made some sweeping constitutional claims, accusing the EPA of violating the Fifth and Tenth Amendments by bullying private businesses and state regulators. But much of the argument in court focused on an esoteric issue involving the wording of the Clean Air Act as it was amended during the first Bush administration. In a situation reminiscent of the most recent Obamacare fight, King v. Burwell, the 1990 amendments had never been properly reconciled by Congress and thus contained two versions of Section 111(d). The bizarre mistake had taken on importance only decades later, when the EPA decided to use the provision to regulate carbon from power plants. Tribe argued that Congress never intended to slip a massive expansion of federal regulation into what might be viewed as the legislative equivalent of a typo.

Even defenders of the EPA recognized that the wording presented a problem: Though the version they preferred appeared to give the agency clear authority, the other was more ambiguous. The Clean Air Act is a clunky device for regulating carbon — that’s the reason Obama had first pressed for his cap-and-trade plan, which would have established a market-based system through congressional legislation. Still, a 2007 Supreme Court decision expressly allowed the EPA to treat carbon as a pollutant, and Tribe’s opponents couldn’t fathom how he had managed to escalate a statutory quibble into a crisis on a par with notorious abuses of executive power, like Harry Truman’s seizure of the steel mills.

Freeman says she felt “awkward” criticizing a colleague she otherwise respects but that she was obliged to speak out against what she sees as misleading rhetoric. “The worst of it is no one will stop and ask about the quality of his arguments,” Freeman says. “They just hear Larry Tribe say that the Constitution is ‘burning,’ and they take it on faith. It’s like Yoda has spoken. I’m not saying the EPA’s power-plant rule is perfect — it’s not. But ask anyone with any real expertise in this area, and they will tell you that the constitutional claims are fictions of the coal industry’s imagination.”

In 1977, when he was 36 years old, Tribe took on the gargantuan project that established his reputation: a treatise that sought to synthesize everything there was to know about the Constitution. He wrote in a manic frenzy of productivity, an eight-month flurry of all-nighters. Harvard set up a bank of 11 typewriters for him, because he couldn’t manage to change a ribbon. Tribe was a Ph.D. student in mathematics before he turned to the law, and his method in analyzing the law was Newtonian, reducing its workings to seven “models.” In his scholarship, he often seeks to apply abstruse principles from physics. His 2008 book The Invisible Constitution explores the unstated principles that “animate and undergird” the written text like “dark matter.” In the 1980s, he wrote an article called “The Curvature of Constitutional Space” with assistance from Barack Obama, seeking to investigate what the law’s “contours mean for those who might be trapped or excluded by them.”

Tribe has devoted his studies to probing what he has called “constitutional silences,” in part through an expansive reading of the Ninth Amendment, which says that the rights provided by the Constitution are not limited to the ones it specifically enumerates. In 1987, he faced down his ideological opposite in the figure of Robert Bork, who likened the Ninth Amendment to a mere “inkblot.” Tribe had been laying the groundwork for opposition to Ronald Reagan’s Supreme Court nominees — before Bork was selected, he published a book arguing that judicial selection was “too important a task to be left to any president” — and he played a starring role at Bork’s confirmation hearings, offering damning testimony. At the time, Tribe was widely seen as destined for the Supreme Court one day himself, and the conventional wisdom, perhaps oversimplified, is that in helping to foil Bork, he sacrificed his own chances of ever being nominated.

“That’s the reason why he’s an iconic figure,” says Bob Shrum, Tribe’s friend and a political consultant to Senator Ted Kennedy, who helped to rally Senate opposition to Bork. “I said to him, look, you have to make this decision yourself, but if you do this, you have to be aware that a lot of Republicans who don’t agree with you, but kind of respect you, will never, ever, agree to put you on the Supreme Court.” Tribe’s admirers wonder how history might have unfolded if he had heeded his friend’s warning.

“It’s very counterfactual,” Tribe told me. “Because had I not testified against Bork, I might not have been as fervently embraced by liberals as I came to be. Until recently.”

Instead of serving on the Court, Tribe continued to serve as its interpreter from his lofty perch in Cambridge. He is one of two dozen Harvard faculty members who hold the title “university professor.” Generations of students have competed for precious slots in Tribe’s classes and the beneficence of his attention. “I think I have thousands of children,” Tribe says. (His two biological children are both artists.) He told me he sees that patrimonial influence as one of the two most important components of his legacy. The other is his advocacy for expanded rights.

Tribe’s most historically meaningful argument may be one he lost. In 1986, in the case Bowers v. Hardwick, he represented an Atlanta bartender named Michael Hardwick before the Court. Hardwick had been charged with sodomy after police came to serve him with an unrelated warrant and discovered him in his bedroom with another man. Tribe hoped to convince the swing vote, Justice Lewis Powell, that the sodomy law violated the unenumerated right to privacy. After some vacillation, though, Powell sided against him, writing in an internal memo that the assertion that there was no difference between gay and heterosexual relationships was typical of “Professor Tribe, with his usual overblown rhetoric.”

The next year, Powell announced his retirement, and Reagan picked Bork to replace him. After Bork’s rejection, Reagan appointed Anthony Kennedy instead; Tribe testified in favor. Kennedy wrote this year’s gay-marriage opinion, as well as the 2013 opinion that paved the way for it and the 2003 opinion that declared sodomy laws unconstitutional. He also wrote the 1996 opinion in a pivotal case that struck down an anti-gay Colorado initiative, holding that a state cannot “deem a class of persons a stranger to its laws.” The opinion’s wording closely resembled that of an amicus brief written by Tribe. Today, Tribe calls Kennedy one of the Court’s greatest justices — an assessment not entirely free of self-identification.

All along, though, Tribe also took highly lucrative cases representing corporate clients. “I did decide that I would never do something just for the money, and I would turn down lots of offers,” Tribe says. Tobacco companies, for instance. “I mean, if I had all the money from all the cases that I turned down, I’d have ten times as much as I have now.” As the Columbia University law professor Tim Wu recounted in a recent New Yorker blog post, Tribe has made the case against net neutrality on behalf of his client Time Warner and has challenged aspects of hazardous-waste-cleanup laws on behalf of General Electric. He has represented Nike in a case related to overseas sweatshops. In the 1980s, he represented criminal defendants like Michael Milken and the Reverend Sun Myung Moon. Tribe says that he took these cases because, to him, each raised important legal issues, such as a corporation’s right to a fair hearing in the case of G.E., or prosecutorial abuses in the case of Milken.

In 1994, an American Lawyer article titled “The Croesus of Cambridge” described how Tribe had built an informal but thriving law practice, charging as much as $1,200 an hour. One Supreme Court argument alone, in the 1987 case Pennzoil v. Texaco — involving what was then the largest civil judgment in history — earned him a reported fee of $3 million. “In general, it was like, ‘Hey, we love practicing the law, that’s what we do, and they pay us for that, handsomely,’ ” says Brian Koukoutchos, who was a research assistant to Tribe and continued to work with him as a lawyer after he graduated. “Having paying clients,” he says, “allows you the luxury of being able to take on clients that can’t pay.” Today, Tribe works mainly with another former research assistant, Jonathan Massey, who has a boutique appellate-law firm in Washington, which touts Tribe’s corporate work on its website. Massey is co-counsel with Tribe on the Peabody case.

The largeness of Tribe’s reputation, and fortune, made him an equally large target when he came out in opposition to Obama’s climate plan. “There’s an enormous amount of jealousy in the Harvard faculty,” says his longtime colleague Alan Dershowitz, who helped to rally a group of legal luminaries to write in Tribe’s defense in the Boston Globe. “He’s a university professor, he’s made a lot of money, he’s very well known.” In 2005, the law school’s Drama Society put on a satirical musical skit, “I’m Larry Tribe,” set to the tune of “I Will Survive.” An actress playing Elena Kagan, then the school’s dean, sang:

He’s ten feet tall!

He learned to fly!

And though he’ll never be a Justice

He’s never gonna die

He is the sultan of Sudan

He is the closer for the Sox

And the legal fees he charges

Make him richer than Fort Knox!

The affection between Tribe and Kagan is real and long-standing. For a time after her graduation, she lived in the finished basement of his family’s 19th-century frame house off Brattle Street. But Tribe has said that among all his students, none was finer than Barack Obama. It is a measure of Obama’s easygoing ambition that soon after he arrived at Harvard Law, he sought out its most prominent faculty member. Tribe marked the day of their first meeting on his calendar with an exclamation point. Obama helped him to write the physics article and a book about abortion. They would talk through case law while taking long walks along the Charles River.

Tribe remained in touch with Obama after he graduated and was one of his early political champions. He introduced his “inspiring” former student to the people of Iowa in a 2007 campaign ad. On the night of the 2008 election, Tribe emotionally embraced Obama in Grant Park. “As a nation,” he wrote in a blog post the next morning, “we have come of age.” In anticipation of an influential role in the new administration, Tribe prepared to move to Washington. When he got there, however, he discovered that Obama hadn’t changed politics. “It’s not just all the terrible things that people say behind each other’s backs,” Tribe says. “It’s how jealous people are of their turf, even when you are part of the same administration.”

Tribe was offered assurances of a high-level job. In 2009, he wrote a private letter to Obama suggesting a “newly created DOJ position dealing with the rule of law.” He seemed like an ideal candidate to sort out dilemmas like Guantánamo. “I thought that for me to be giving broader advice on constitutional issues would make sense,” Tribe says. “But it was clear that was stepping on people’s toes.” He instead took a nebulous Justice Department job, “senior counselor for access to justice,” and did grassroots work like aiding homeowners facing foreclosure. Still, some colleagues remained resentful of his relationship with the president. Obama occasionally summoned him to the Oval Office to talk about abstract issues of law, but even those rare interactions created friction.

“Rahm Emanuel pulled me aside at a party at the W Hotel,” Tribe recalls. “He said, ‘I heard you went to the Big Guy behind my back.’ ”

Tribe was dealing with health problems, complications from an earlier surgery to treat a benign brain tumor, as well as the emotion and expense of what he described in the Washington Post as “a very contentious divorce” from his wife of four decades. (He told the Post that Kagan was one of his few confidantes.) But the low point came in the form of a leak. A blog obtained that 2009 letter to the president in which Tribe had mainly addressed the subject of future Supreme Court appointments, offering praise for Kagan and an uncharacteristically harsh assessment of another leading candidate, Sonia Sotomayor. “Bluntly put, she’s not nearly as smart as she seems to think she is,” he wrote, “and her reputation for being something of a bully could well make her liberal impulses backfire.”

“I could hardly have been more wrong, and it was foolish of me,” Tribe told me. (In Uncertain Justice, he is conspicuously complimentary of Sotomayor, calling her a “judge’s judge” and comparing her to Earl Warren.) Kagan and Sotomayor were both on the Court by the time the letter emerged in late 2010, so it only served to damage its author. Citing his health, Tribe soon resigned. “I assume someone in the administration leaked it to injure Larry,” Tom Goldstein says. He believes the letter had to be understood in the context of Tribe’s relationship to Kagan. “It’s just Larry being unbelievably loyal, and somewhat tone-deaf to the prospect that someone could use it to hurt him later on,” he says. “He is a thinker, not a maneuverer, and that means he can very easily be outmaneuvered.”

Tribe told me he hasn’t spoken to the president in almost four years and hasn’t had any direct communication with the White House about the EPA case. “It’s all mean anonymous quotes,” he says. But he would very much like to know how Obama regards him today. “Do you really think that Barack or people close to him are pissed at me?” Tribe recalls asking his former research assistant Ron Klain, who was Vice-President Biden’s chief of staff. “He said, ‘No, I think they realize that your credibility when you’re on their side is enhanced by the fact that you’re not always on their side.’ ”

“He’s assuming a largeness of spirit,” he says, “that may or may not be there.”

While representing the coal industry had caused Tribe personal pain, it has been good for his personal business. Lately, he’s been getting many calls about regulation cases. One new client is a New York real-estate investor who wants to challenge the city’s plan to rezone part of midtown, arguing it would devalue his air rights. Another is the American Clinical Laboratory Association, which is fighting a Food and Drug Administration effort to expand its regulatory power over certain types of medical tests.

“Some of my best friends have severe, metastatic cancer, and they’re depending on rapidly evolving lab tests, and they’re going to be killed by what the FDA wants to do,” Tribe told me over lunch one day in Washington, where he was to speak to the laboratory association’s annual convention. He later shared the dais with Paul Clement, probably the foremost conservative Supreme Court advocate. “If Larry and I agree,” Clement told the audience, “that right there ought to give you some comfort.” Tribe called the FDA’s case for regulation a “fairy tale” and issued a dire warning about its import. “What I fear down the line, if the FDA succeeds in getting the camel’s nose under the tent here, is a federalization of the practice of medicine.”

There has always been an anti-regulatory component to Tribe’s thinking. As far back as the 1980s, he was decrying the “trend toward granting bureaucrats and professionals ever-increasing power over our lives and liberties.” For decades, this strand of consistency has allowed Tribe to balance the roles of liberal and litigator without internal conflicts or much public criticism. And though Harvard is one of the country’s highest-paying universities, Tribe has always felt the need to supplement his income. “I wasn’t in a position to turn down money when I believed in the case,” he told me. Like many people who grew up without money, he has always worried about it.

Tribe entered Harvard at 16 as a scholarship student, worked in the kitchens, and was tormented by his older roommates, who had gone to schools like Andover and Exeter. His father, born George Israel Tribuch, never made more than $15,000 a year as a car salesman. The family immigrated to San Francisco, when Tribe was 5. They came from Shanghai, which had a beleaguered little community of Jews who had moved east to escape pogroms and, later, Hitler. Tribe claims that he has a vivid memory of a day when he was about 2 and his father was taken away to an internment camp by the occupying Japanese. “That imprinted the feeling,” he says, “that there must be something wrong when people can be hurt for no reason.”

As Tribe would be the first to say, though, originalism has its explanatory limits. Why, of all the injustices in the world, would he expend his own valuable energy fighting rules on carbon emissions? Even many of Tribe’s friends have trouble answering that question. “Maybe some people are willing to embrace the idea that the end justifies the means in constitutional law,” Tribe said one morning over breakfast in Chautauqua. But he says he thinks in terms of rights, not outcomes. When he wrote about environmental protection early in his career, he proposed creating “rights for natural objects.” He has argued that laboratory chimpanzees should have the right to sue for habeas corpus. He has come to the conclusion, reluctantly, that the Second Amendment protects the rights of individual gun owners, within reason. He does not discount the idea that corporations have a right to political speech and takes a measured view of the Citizens United decision.

“Larry believes in a big Constitution,” Goldstein says. “A big Constitution can protect a lot of little guys, and it can protect a lot of big companies.”

Tribe’s relationship to the Constitution can seem sentimental — even empathic. He once wrote that before his first Supreme Court argument, shortly after his father’s sudden death, he saw a shooting star, which he took to be his father’s spirit, and he began to associate the apparition with the Constitution’s “affirmation of rights unwritten and unseen.” In March, when Tribe testified against the EPA plan at a House subcommittee hearing, he staked out his position in romantic terms. “A lot of my friends tell me, ‘Look, don’t be an idealist, don’t be utopian,’ ” he said. “ ‘Congress isn’t going to do anything, so why are you so hot about the EPA violating the law and the Constitution?’ Well, it is just, I guess, the way I was brought up. I think the law and the Constitution matter.”

The Republicans on the subcommittee fawned over the esteemed Professor Tribe. Environmental advocates suggest that he really has no case, that the coal industry is trying to stall, spreading doubt that might cast a pall over an important round of international climate negotiations this fall. Over the horizon looms the possibility of a Republican president. “The constitutional arguments that Tribe is making are not serious arguments,” says Richard Revesz, a New York University professor who sparred with Tribe at the hearing, pointing out that the EPA has been regulating air quality for 45 years. “They are weak arguments, and they are not being made to win this case. They’re basically being made to mislead the public and weaken the president.” C. Boyden Gray, who helped to draw up the 1990 Clean Air Act amendments as counsel to the first President Bush, and now represents many energy-industry clients as an attorney in private practice, told me in June, after the initial case was dismissed, that there were many legal arguments to be made against the EPA carbon regulations — but he wasn’t convinced by Tribe’s. “You look at Revesz,” he says, “and you say, ‘My God, that is pretty persuasive.” (On behalf of a client, however, Gray has since filed a federal appeals court brief endorsing Tribe’s position.)

Why would someone as acclaimed and intelligent as Tribe advance a case that even some serious Republicans have treated skeptically? One possibility is that he is doing it for the money alone, but those who have worked with him say that’s not how he operates. “Larry doesn’t take cases out of a sense that they are fashionable,” says Kathleen Sullivan, a former student who collaborated with him on the Bowers case as a Harvard professor and went on to become dean of Stanford’s law school. “He takes them because he profoundly believes in the essence of the argument.” Some critics suggest that Tribe’s problems emanate from this stubborn insistence on sincerity. Why could he not just admit what seems obvious to them: that, after all, he is just a lawyer? “They would like that, because they think that would reduce the academic patina,” Tribe says. “But it would also be false.”

Another potential explanation was set forth by Tim Wu, who was willing to accept that Tribe genuinely held his opinions but articulated “the suspicion that Tribe might well hold different, if equally sincere, beliefs had he not been loyally representing so many corporate defendants for so long.” The problem, Wu suggested, was not that Tribe didn’t believe his arguments but that he really did. From Tribe’s perspective, this accusation is the most infuriating — he can’t refute the claim that his own mind is captured.

There’s also the possibility that Tribe simply understands the Constitution better than his adversaries. In the end, he only has to win over one audience, and he thinks the Supreme Court is ready to listen to his opinion. Roberts, who has called bureaucracy “the headless fourth branch of government,” seems eager to mount an offensive against the regulatory state. Though Roberts voted against the plaintiffs in King v. Burwell, his opinion included a sharp rejection of the Chevron deference principle — a seed of reasoning that could eventually blossom into anti-regulatory doctrine. “There are strategic justices who play four-dimensional chess,” Tribe says. “Roberts is clearly like that.”

Though Tribe calls Roberts “canny,” he has been sharply critical of his Court’s conservative direction on many issues. He says that some of the chief justice’s colleagues complain about his style. (“They all loved Rehnquist, and they don’t all love Roberts.”) He sometimes jokes that, in contrast to other students, Roberts seems not to have absorbed all of his class material. So it is a bit ironic that Tribe is now pinning his hopes for vindication on the Court’s right wing. But life, like the Constitution, is always evolving in interesting new directions, and Tribe thinks that the wind of the Court’s opinion is at his back.

In June, after the Obamacare decision, I forwarded Tribe the link to an article in the publication Greenwire that raised the possibility that the same reasoning that benefited Obama on health care might serve to foil his climate policy. He replied:![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

*This article appears in the July 27, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.