We got a little hint last week about what the next $10 bill will look like, and it is almost sure to involve Alexander Hamilton. The cast of Hamilton, led by Lin-Manuel Miranda, visited Washington and toured the Treasury, and Secretary Jack Lew all but told Miranda that A.Ham’s face won’t be coming off the money.

This news semi-contradicted earlier rumors, floated when the redesign was announced, that said the Treasury would kick A.Ham off the $10 to make room for a woman honoree. Lew implies, therefore, that Hamilton will get some female company. And that makes sense, because everyone seems to forget a key fact about our awkward bill designs: It’s not the faces that need redoing but the other sides. The faces of our bills, while busy and awkward owing to lots of anti-counterfeiting measures and accrued historical details, at least have a center: the portrait, and particularly its eyes. The green backs of our greenbacks are total throwaways. That’s where we can, and should, be adding honorees.

Consider the current $10. Hamilton looks pretty soulful, and, as we have all learned from Miranda, he certainly deserves to be there. And on the back of his bill is … the Department of the Treasury’s headquarters. Not only is it completely static; it’s not even a building anyone cares about. Barely any tourists visit it; no architectural historian writes about it. Yet we give it space that could be used to honor some inspiring American. That’s ridiculous.

The other bills are vaguely better, only because they show monuments you might want to visit: the Lincoln Memorial, the White House, Monticello, the Capitol, Independence Hall. But they all (apart from the $1, about which more later) still show buildings. Why? Probably because they are horizontal and fit the space, and because when our currency took its more or less current form in the 1920s, neo-Colonial architecture was in vogue. The Lincoln Memorial was brand-new. So highlighting these buildings may have seemed fresh at the time; it’s dead now.

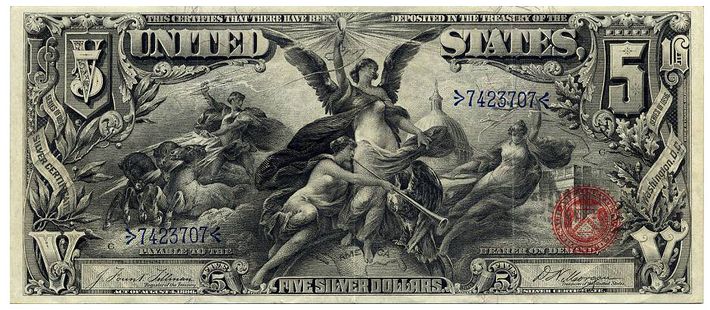

It was not always thus. Consider this 1896 bill, from a short-lived design that (covetous) collectors call the Educational Series:

There’s a lot going on, for sure. Allegories are everywhere; this particular one is supposed to be about electricity sweeping in and enlightening the world. The single and the $2 bill were nearly as complex and figural. But the key thing is this: Every bit of that piece of paper is in play, and it is artistically ambitious. On the reverse, there are two portraits, of generals Ulysses Grant and Philip Sheridan (we were only a few years out from the Civil War). After all, there’s no rule saying we can put only one person’s face on a bill.

In fact, a pair of portraits was once commonplace. Here’s a note from the same era on which George and Martha Washington face each other. Martha, so far, is the only woman to appear on American cash, apart from nonspecific figures of Liberty and, briefly and unsuccessfully, Susan B. Anthony. (Update: Readers have pointed out that Sacagawea appears on the $1 coin, although it’s not exactly a portrait of her since we have no idea what she looked like. Similarly, a made-up Pocahontas once appeared on a $20 bill, kneeling as she was baptized a Christian. And in the realm of limited-run commemorative coins, Helen Keller and all the eligible First Ladies have appeared, or will do so shortly.)

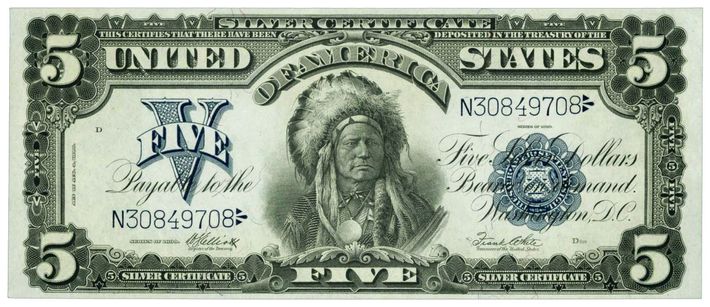

Other times, the images (front or back) have simply been creative tributes to otherwise unrepresented Americana. A Pawnee chief named Running Antelope once appeared on the $5:

And even a bison made it for a while:

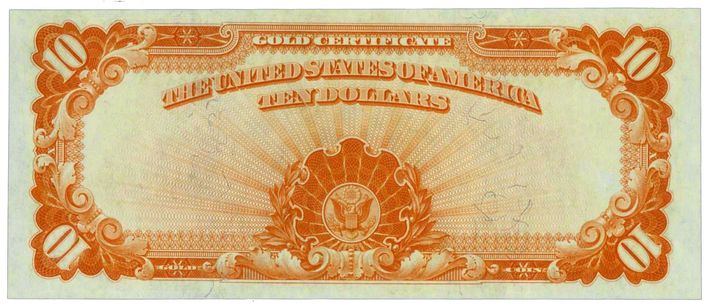

Still, other times, even into the 20th century, the backs of bills were almost totally abstract, in colors other than green. Consider this cheery gold certificate, from 1907:

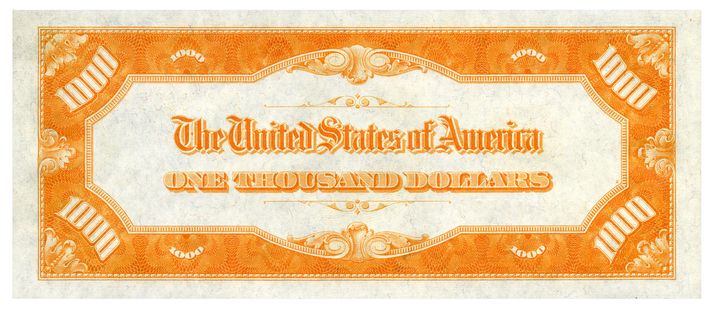

Or this one (on a version of the now-discontinued $1,000 bill):

Thin the filigree out just a little, and the backs of both of those bills would look like letterhead for a Brooklyn artisanal-blacksmithing firm. If we had money like this, your font-geek friend would spend hours staring at it every time he opened his wallet.

* * *

Any American no longer living is eligible to appear on currency. In this conservative country, we are unlikely to demote anyone who’s already on our cash, with the vaguely possible exception of the very hard to defend Andrew “Trail of Tears” Jackson. Never mind that four of the seven men on our cash were slave owners; they’re almost surely staying. Since we have decided — or I have, anyway — that we’re going to start putting more than one face on a piece of currency, the question then becomes: Should the people on a given bill be connected in any way? I think so: There is a tidiness to that, and (as in the casting of Hamilton) it allows us to break up the whiteness and straightness of the history most of us grew up with. (“Who tells your story?”) So if the dead presidents stay on the front, the reverse is a place for counterprogramming, and here’s a proposal: Make each bill thematic.

The $100, which now honors Benjamin Franklin, should likely be about invention and technology. Thomas Edison is the obvious choice to complement him. (Nikola Tesla would also be a nice partner, as would Alexander Graham Bell, but convention has it that only American-born figures can appear on our money.) I’d also put in a vote for the Wright brothers, whose achievement grows more astounding the more you learn about it. This spot, at least, would be difficult to give to a woman; until very recently, science and engineering were pretty obdurately male. Important a figure as she is, Grace Hopper is not Thomas Edison. If a pure scientist is your preference, we’ve got ranks of them: Linus Pauling and Richard Feynman come to mind most quickly. (By the way, these lists of suggestions are not based on any inside information or official choices made by the Department of the Treasury, and I am sure that at least a couple of the people I am suggesting, upon close examination of the historical record, will turn out to have committed some horrible disqualifying behavior.)

Ulysses Grant, on the $50, is there to mark the Union victory in the Civil War, and by extension abolition. Harriet Tubman has been much discussed to replace Hamilton on the $10, but she would probably be a better, and perhaps more corrective, partner for Grant. Frederick Douglass would also be a fine choice; so would Sojourner Truth.

If we’re keeping Andrew “Problematic” Jackson on the $20, perhaps we could at least point up his horrifying forced marches through Oklahoma by making this the Great Plains note. The list of Midwesterners made good is huge: Frank Lloyd Wright? Georgia O’Keeffe? Andy Warhol? (He was from Pittsburgh, but close enough.) Heck, I’d make a case for Charles M. Schulz, even. Alternatively, if you want to honor Jackson as a son of Tennessee, a certain Memphis performer comes to mind.

The $10, being home to Hamilton, is clearly about economics, so that’s a place for a great American business figure. We would have to make this selection carefully, owing to certain, ah, issues with the likes of Henry Ford and Thomas Watson and John D. Rockefeller. I myself would choose Peter Cooper, a great New Yorker who gave to found a New York institution (among many other things). He would also look fantastic in the engraving, because of that beard of his. But, short memories and Apple fanboys being what they are, I suspect that Silicon Valley will put on a full-court press for Steve Jobs.

Abraham Lincoln on the $5? We have already devoted the $50 to manumission, so let’s take another angle for this one: Lincoln’s gift with language. That leads us to literary figures. Mark Twain? Willa Cather? Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald? Or Edith Wharton! Seeing a sly New York novelist on every five-spot would make your morning Starbucks purchase that much more appropriate — especially if you bought it in her house.

The $2 bill, on which Thomas Jefferson appears, doesn’t see much attention, except in one unexpected setting. Since it has no associations, we can treat that as a freeing possibility: Nobody cares who appears on it, so we can put an outlier on the back. Because the stakes are low, we can place a figure whom everyone appreciates but who has no chance of appearing on any bill, ever again. How about a sports star? Especially an African-American one, given Jefferson’s particularly troubling story. Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, Arthur Ashe … I’ll leave it to WFAN and Deadspin to take great pleasure in arguing out the choice.

And the single? The Treasury says it’s not going to be redesigned, probably because there aren’t many counterfeiters bothering with $1 bills, so that’s that. Just leave it alone, in all its pseudo-Masonic weirdness. And, anyway, we don’t need to; what we need to do is stop printing $1 bills altogether, an argument I have made elsewhere.

Or, alternatively, you could throw all of these folks off the money and do as the Dutch did on arguably the most amazing bill ever circulated. It’s one of the final designs for the 50-guilder note, from the ‘80s, shortly before the euro swept in. Flowers!