Many have been trying to understand and weigh in on the legacy of Muhammad Ali following his death on Friday. From sportswriters who followed him from the beginning of his career, to current and former presidents, to people who’ve only seen his fights on YouTube but still feel the magnitude of his contributions to America and the world. As David Remnick summarizes in The New Yorker, Ali “became arguably the most famous person on the planet, known as a supreme athlete, an uncanny blend of power, improvisation, and velocity; a master of rhyming prediction and derision; an exemplar and symbol of racial pride; a fighter, a draft resister, an acolyte, a preacher, a separatist, an integrationist, a comedian, an actor, a dancer, a butterfly, a bee, a figure of immense courage.” But one of the most interesting threads across what has been published this weekend has been a conversation over Ali’s role as a black icon, one who challenged America as much as he challenged his opponents, and in doing so, as longtime friend and sports columnist Jerry Izenberg wrote Saturday, forged a bond “with a constituency that didn’t have to meet him to know him, a constituency that transcended all economic, racial, ethnic and political barriers” — all while being an actual person with flaws mixed into his multitudes.

One of the sports reporters who covered Ali for most of his career, Dave Kindred, tackles this problem head on in his remembrance, which was published on Fox Sports. Like others, he describes and analyzes Ali’s athletic accomplishments, but he also tries to encapsulate the scope of Ali’s cultural impact. Regarding an origin point, Kindred focuses on a single statement that Ali, or Cassius Clay at the time, made to a group of reporters the day after his shocking defeat of Sonny Liston in 1964 to claim boxing’s heavyweight title for the first time:

I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be who I want.

Clay made the comment after being badgered by the reporters, following his post-victory acknowledgment that he had converted to Islam and joined the black separatist Nation of Islam. (Clay would soon change his name as well.) Faced with that initial backlash, Clay made the above statement in what Kindred and others consider to be a kind of Declaration of Independence:

There. Two sentences. Whatever came after that day – an epic saga came after that day – its foundation was Ali’s 18-word rendering of a complex idea. Though he lived in a society that oppressed black people, he would not give away his right to the life of his choice. On that day he foreshadowed a coming generation of African-Americans: black and proud of it.

But while Ali would rightfully become a black icon and world-historical figure, Kindred also emphasizes that the man “was no saint,” passing along a reality-check question he was once asked by another longtime sportswriter who covered Ali, Sports Illustrated’s Mark Kram:

How can people consider Ali a historic figure from the 1960s? He wasn’t for civil rights; he was for separation of the races. He wasn’t for women’s rights; he treated them like second-class call girls. He was never really against the war; he was told not to go by Elijah Muhammad because it would be a PR disaster for the Muslims. These were the hot issues of the ’60s, and he was on the wrong side of history in all of them. Yet people today somehow think Ali belongs right next to Martin Luther King. Why isn’t it enough for people that Ali was the greatest fighter ever?

But Kindred goes onto to explain that, no, it was not enough, and Ali answered the moment, in a way he simplifies thusly:

The most famous man in the world said no to war at the risk of imprisonment by the most powerful nation on earth. It didn’t matter how he came to that decision. It mattered only that he risked his future on it. He never wavered, and he gave heart to millions of ordinary citizens who thought that war was as unwise as it was unjust. He was on the right side of history.

The most famous man in the world was a black man from Louisville, Ky., who raised his chin a zillion times to shout, “I am the greatest!” It didn’t matter if he had come down with the all-time champion case of runaway narcissism. He believed he was the greatest, he lived it, and he gave voice to millions of people who had been told, taught, and otherwise commanded to be silent. The right side of history, again.

Name anyone else who did all that and did it while being the greatest athlete I ever saw or ever will see.

In President Obama’s statement on Ali’s passing, he focused on another definitive statement from the champ and on the personal significance of Ali’s role as an inspiration to him and other black Americans:

“I am America,” he once declared. “I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me – black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me.”

That’s the Ali I came to know as I came of age – not just as skilled a poet on the mic as he was a fighter in the ring, but a man who fought for what was right. A man who fought for us. He stood with King and Mandela; stood up when it was hard; spoke out when others wouldn’t.

Wesley Morris tried to capture the significance of Ali’s blackness in a piece for the New York Times:

Officially, black is a who. But with Ali, it was always a how. How do you use your blackness both for and against? How is it helping? How might it hurt? How is our own blackness being turned against us?

When he left boxing after his last fight in 1981, he took the majesty of the sport with him. He took the symbolism and grim spectatorial history, too. Boxing is a two-man contest. But if Ali was in the ring, so was the rest of the country.

Vann R. Newkirk II agrees, noting in The Atlantic that “Ali was one of the greatest boxers of all time, no doubt, but I’ve found his true skill to be his role as a public intellectual, expressing his unapologetic blackness in the face of life-threatening danger”:

That voice reverberates today. Even in death, Muhammad Ali is everywhere. He is in Mike Tyson’s fast-talking menace. He is in Michael Jordan’s singular greatness and arrogance. He is in Russell Westbrook’s scowl, Steph Curry’s public religiosity, and Cam Newton’s smile. He is in Serena Williams’s dominance. He is in President Obama’s swagger. He is in hip-hop; his quotes have been pretty much the bedrock for the art’s boasts of masculinity. His anti-war stance, racial philosophy, and confrontation as praxis are directly evident in black millennial protest today. Fanciful a thought as it may be, I like to envision that some of him speaks through me as well.

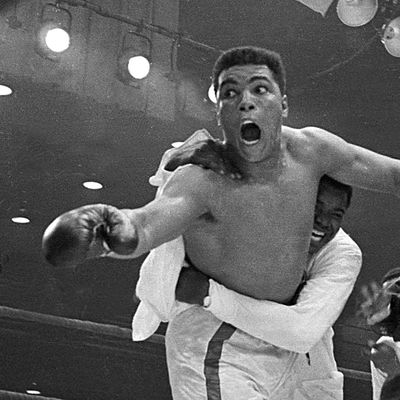

Writing for the Undefeated, Jonathan Eig zoomed in on one match that defined Ali’s unapologetic pride: his 1966 title-defense bout with Ernie Terrell. That match was preceded by a televised interview in which Ali became enraged at Terrell for referring to him by his former “slave name,” Cassius Clay. In the subsequent fight, Ali eventually began to dominate Terrell and started shouting, “What’s my name?” at him as he attacked. Eig explains that Ali was later accused in the media of being a thug and torturer for how he treated Terrell, but argues that was not the only view of what happened:

[W]hile the white press vilified Ali for bullying Terrell, many black Americans took a different view. They saw Ali as a man exploding with pride and anger. They might not have embraced his religion, but they could relate to a man demanding dignity. Before Ali, black athletes were expected to show respect for authority, to be thankful for the opportunities white America gave them. Ali beat the crap out of that notion.

What’s my name? What’s my name?

The Atlantic’s Gillian B. White shares what that kind of contagious pride would mean for her father:

It wasn’t just Ali’s pride, it was his pride about who he was — black, Muslim — at a time when society didn’t encourage men like him to have any pride or voice at all, that really struck a chord with my father. Whether or not he agreed with his views on Vietnam or refusal to fight did not matter. At a time when black men were supposed to apologize and accommodate, to simply keep their heads down and do as they were told, Ali’s push to stand up for himself and his beliefs was invigorating. While my father’s childhood included vivid memories of segregation, of racial violence, of the fight for basic rights, they also included the hope that one day this country would be a more equitable and welcoming place for people like him. Ali’s radicalism could help make that hope, reality, he thought […]

Ali did not transcend race. His singular life and achievements can never be divorced from his identity as a black, Muslim man. He forced America to wrestle with an iteration of black excellence that wasn’t quiet, or ashamed, or defined by white people. By defining himself through word and deed, Ali taught other black people that they could, too.

And MTV’s Jamil Smith details what he learned when his dad made him watch a recording of Ali’s epic 1974 Rumble in the Jungle with George Foreman, in which Ali used his now-infamous rope-a-dope strategy to tire out the more powerful Foreman and ultimately defeat him:

Patience alone isn’t a virtue. That was an important thing for me to learn as a young black boy. Do not just endure abuse for the sake of appearing stoic and manly, but endure with a firm purpose in mind. Endure until a pathway to victory opens. Letting your opponent believe that you’ve lost, sometimes, can be to your advantage. Granted, it isn’t the most optimistic or triumphant way to think about winning. It isn’t the classic hero’s narrative. But I learned that vital lesson better from Muhammad Ali in that ring than I did from any civil rights leader or war hero. [His life] was never solely about winning, but about conflict, and finding the best ways to navigate it while never compromising who you are. May we all be so agile on the ropes we find pressing at our backs, until the time is right to strike.

And then there was the importance of Ali to Muslims all over the world, but especially in America, as Aisha Sultan celebrates in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

This legend chose a spiritual home. He chose Islam. He chose this faith I share with him, a religion maligned so often in this country. He showed us what you have to do when a nation turns against you. When a government suspects you. When you are stripped of an achievement you bled and battled for. You double down on courage and strength of character. This man known as The Greatest, he was a Muslim. His moral clarity sprung from that truth.

He belonged to all of us. But we needed him the most. He filled Muslims in America with pride we could not have known without his rise, his fall and his return. You can remember Muhammad Ali for his athleticism, his feats in the ring, his courage outside of it, his generosity and spirit. We remember all that and his uncompromising, unapologetic devotion to this faith. The greatest fighter who became a great champion for peace around the world. He was a Muslim. He was part of a family of more than a billion who adored him. He was ours.

Of course, the fight within the boxing ring would also ultimately take a chilling physical toll on Ali, and that sacrifice is what troubles the Undefeated’s T.J. Quinn, who, when considering the arc of Ali’s career and the mainstream public’s acceptance of him, points out that Ali “had to be punished before he could be loved”:

Ali entranced so many black Americans with his genuinely rebellious militancy and his willingness to forgo the trappings and the windfalls of being an “acceptable” champion to white America. And he inspired white Americans who sought a similar rejection of the old order and wanted to tear down constricting structures. But his transformation to cross-cultural icon came only after breaking with the Nation of Islam, and then slowing down in the ring and losing terrible fights and, finally, becoming an international ambassador for peace.

That Ali was no longer a threat:

The solidity of his convictions and his willingness to sacrifice on behalf of a principle became clear for some only in the safety of hindsight, free of the threat he once posed to both convention and the psyche. The adoration of his brashness came retroactively and washes away the memory of internal surges that so many whites, and even conservative blacks, felt while watching him verbally ramble, begging for somebody to please step forward and slap that […]

In that sense, the defanged Ali became a handrail for Americans who needed to make the next leap in racial thinking, with other leaps still to come.

At the Root, Lawrence Ross is similarly critical of America’s late acceptance of Ali:

In essence, the latter years of Ali’s life saw his voice gentrified to what white America felt was safe. Standing ovations at arenas, concerts, and University of Louisville games, where he’d be wheeled out to midfield to receive the adulation of a city where he’d once said, “blacks were treated like dogs.” Had the plight of African Americans in the city changed, and if so, what did Ali think about that change? That we’ll never know, as he’d been reduced to people shoving a microphone close to his mouth, hoping for a whispered funny line or two, that sizzle that had one time talked about floating like a butterfly, and stinging like a bee. But never the powerful political voice of the 1960s and 1970s, the one that had demanded rights for those without them.

Ali the Idea became real, as Ali the Man receded. The universal hero, black and white, Democrat and Republican, north, south, east and west, it didn’t matter. The Ali voice that demanded something of a white America that intentionally forgot about the plight of minorities was now itself forgotten. And that’s the great tragedy. For the past thirty years, we lost our ability to listen to an authentic Ali voice.

So now that he is dead, we have to ask the question as to who gets to decide which Ali voice gets heard and remembered. Which Ali voice, the one that challenged America to be better, or the one that imagines Ali being the silent façade on which he could mean everything to everyone?

Nation sports editor Dave Zirin votes for the former:

We haven’t heard Ali speak for himself in more than a generation, and it says something damning about this country that he was only truly embraced after he lost his power of speech, stripped of that beautiful voice. Ali may have seemed like he was from another world, but his greatest gift was that he gave us quite a simple road map to walk his path. It is not about being a world-class athlete or an impossibly beautiful and charismatic person. It is simply to stand up for what you believe in.