There are two 42nd Streets. West of Sixth Avenue, what was once an artery of sordid drear has been almost entirely remade in the last few decades, preserving a few token theaters wedged between towers of glass. Otherwise, renewal marches on: Work has finally ended on Snøhetta’s revamping of the Times Square plazas, the Port Authority hopes to tear down and replace its Eighth Avenue bus terminal, and the western end will eventually get a jolt of energy radiating from Hudson Yards.

East of Sixth Avenue, though, the old stone metropolis has survived, partly because the Landmarks law protects it, but also because buildings that were once advanced and daring have remained doggedly useful as they age. The behemoths of 42nd Street proclaim this city’s nimbleness, its ability to navigate the chaotic present without jettisoning either its history or its dreams.

Walk 42nd Street with Justin Davidson as your tour guide.

Excerpt from the audiobook, courtesy of Penguin Random House Audio.

This has long been New York’s most idealistic street, where fine instincts and modern technology fuse into a boulevard of high-minded civic aspiration. Even its roster of vanished landmarks is a testament to loftiness. This is where the press (the Daily News, the Herald Tribune, the Times, and The New Yorker) has continuously tested the limits of the First Amendment, where pedestrians have reclaimed civic space from cars and dereliction (in Times Square), and where doctors tended to wounded veterans (the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled, which once existed between First and Second Avenues). Charity workers (at the Ford Foundation) tried to staunch the world’s worst ills, and a global financial institution (Bank of America) erected what was then the world’s greenest skyscraper. On 42nd Street, the curious can enter one of the world’s great research libraries and dive into virtually any published book. And half a dozen blocks east of the New York Public Library, diplomats from all over the world convene to hammer out intractable conflicts, not with weaponry but by sitting around a conference table and talking. When you think about it, 42nd Street isn’t just the epicenter of spectacle but also a boulevard of noble ambitions.

1. Times Square

Times Square is a car heaven before it’s a heathen’s paradise.

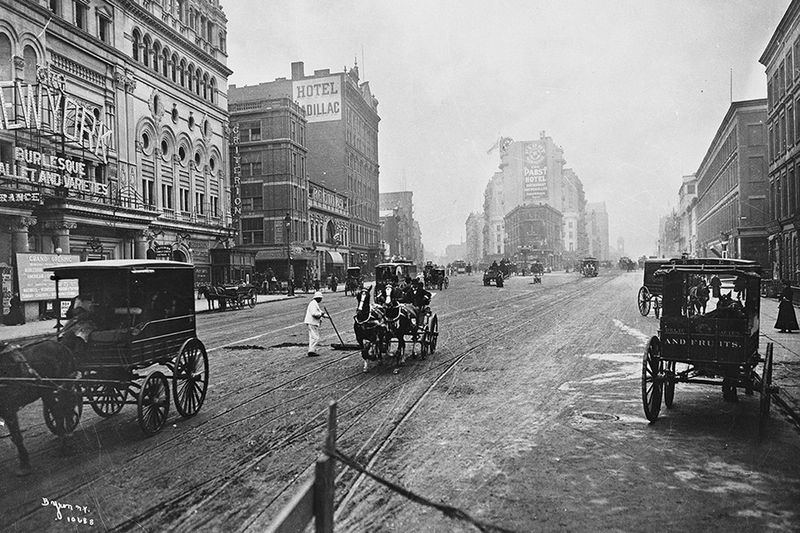

These days, Times Square is perpetually clotted with pedestrians rushing to theater seats and office cubicles or ambling in an LED-ened daze. But at the turn of the 20th century, it was ground zero of car culture. In 1902, Studebaker, a carriage company that had nimbly retooled for the horseless kind, put up a ten-story factory with offices just off what was then called Longacre Square. The building, on Broadway at 48th Street, anchored a row of luxury automotive companies whose showrooms rivaled couturiers for chic. But even in its heyday of glamour, 42nd Street had a reputation for sordidness. From the Civil War to the 1990s, from the slaughterhouses along the East River to the rail yards by the Hudson, this stretch of pavement, pounded by hookers, con men, addicts, and pickpockets, knitted together the most distasteful parts of urban life. By the 1960s, the area had became synonymous with sleaze. And yet it was still the city’s heart. In 1979, Madonna arrived in New York and told a cabbie to take her “to the middle of everything.” He dropped her at Times Square.

The Times Square of today, with its glass and glare, its polished granite benches and scarlet stairs, is the product of a protracted rescue operation. Determined to redeem it from crime and porn, the city turned it into a white-collar-and-entertainment complex, where lawyers, publishers, tourists, theater people, and reporters all shove past each other on expanded but still overflowing sidewalks. It is a place that everyone professes to hate but is always full.

2. Bryant Park

America’s biggest building rises on the site of Bryant Park.

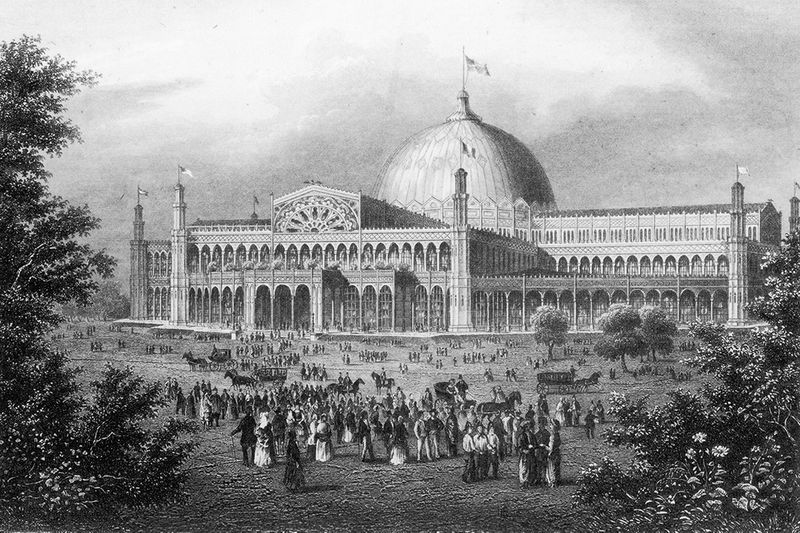

It’s July of 1853, and the Crystal Palace, all airy cast-iron lacework, topped with a great glass dome, is the largest building America has ever seen, built in just nine months to house the “Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations,” where according to the official catalogue, experts demonstrate “specimens of New-Orleans long moss for upholstery purposes,” immense, clanking steam engines, “an improved machine for breaking and dressing flax,” maps, window dressings, pistols, scythes, and “philosophical instruments.” Walt Whitman visits the exposition again and again. Nearly two decades later, he will write “Song of the Exposition,” which still quivers with the freshness of that first encounter with the industrial arts:

Around a Palace,

Loftier, fairer, ampler than any yet,

Earth’s modern Wonder, History’s Seven outstripping,

High rising tier on tier, with glass and iron façades.

And yet, the Crystal Palace barely lasted, collapsing in a quick and violent fire after just three years. A few decades later, the promise of the future underlying this very spot devolved into the kind of urban ghastliness that sent millions skedaddling to the suburbs. It’s not happenstance that in 1952 Ralph Ellison chose the street just outside Bryant Park as the setting for a viciously climactic moment in Invisible Man. Ellison’s narrator comes across the once-proud Brother Tod Clifton selling Black Sambo dolls on the sidewalk, making them shimmy in a grotesque minstrel dance at the end of a thread. When a policeman bears down on him for lacking a vendor’s permit, Clifton lashes out, effectively committing what we now call “suicide by cop.”

By the ’70s, these blocks formed a frightening caricature of urban threat. “It’s a dangerous park,” a groundskeeper told the Times in 1976. “There’s a crew in this park, all they do is walk around and mug people. It goes on all day.” A demoralized community-board chairman suggested that the only way to disinfect Bryant Park of crime might be to close it completely.

The 1990s cleanup of Times Square spread eastward, too. Now, out on the sidewalks beyond the park’s balustrades, New Yorkers move with a determined stride. The Bank of America Tower, a cream-white glass behemoth designed by COOKFOX Architects, disgorges lunchers. If you scooped up a shovelful of passersby at any given moment, you’d collect specimens from most of the world’s nations and the full economic spectrum from homeless person to plutocrat, with every gradation in between.

3. New York Public Library

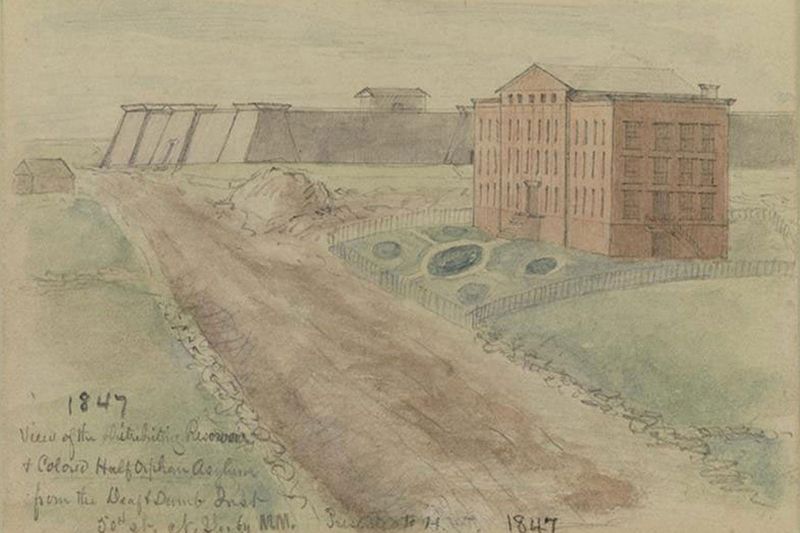

A freshwater reservoir becomes an intellectual repository.

Sunrise, July 4, 1842: A handful of early risers have gathered to witness a miracle of engineering. This island in a tidal estuary, laced with murky canals and surrounded by brackish currents, has been in dire need of clean, drinkable water. Here it comes, piped in from the Croton River, muddy at first, then clear and sweet. It rushes through 45 miles of tunnels that have been blasted and dug and lined with brick, crosses the Harlem River atop High Bridge and into the vast 86th Street reservoir (in what will later become Central Park), and flows into the great cistern at Murray Hill. From here, it will branch into narrower pipes and splash from public fountains and newfangled fixtures in private homes. The Croton Reservoir — a perfectly square, battlemented perimeter guarding a four-acre enclosure — is really just a holding tank, but it’s the most visible juncture in an immense new aqua-management system that will soon tip New York into a global metropolis. Over the rest of the day, 25,000 people will converge on the reservoir to watch it fill and to line up for a free drink of ice water.

The Croton Reservoir took years of planning and the then-colossal sum of $13 million to complete, and there was plenty of grumbling at the extravagance and delays. After all, New Yorkers were not accustomed to receiving much in the way of municipal services. The city still lacked a police force, garbage collection, with electricity decades away, and it had only the sketchiest form of public transit. Not everyone saw the need for those embellishments. But in July 1832, cholera attacked, killing thousands and inciting many more to flee. Three years later, fire decimated the mercantile core around Wall Street, destroying 700 buildings. On that frigid night, in December 1835, firefighters could only stand helplessly by, water frozen in their pumps, until they were finally able to stop the destruction by demolishing unburned buildings and creating a firewall of rubble. Suddenly an aqueduct looked like an instrument of survival. Its architecture invoked ancient Egypt, and its scale seemed eternal in a city destined for rapid change.

As it happened, it would last only 60 years, by which time a far more extensive web of pipes made the reservoir obsolete. That’s the thing about New York: Today’s unimaginable ambition becomes tomorrow’s quaint relic.

The New York Public Library sits right where the Croton Reservoir did, and it, too, wrestles with the challenge of keeping idealism up to date. Since the day the library opened in 1911, anyone, from the barely literate to the Nobel laureate, could pass between the friendly lions named Patience and Fortitude and climb the imperial-scaled stairs to the third-floor Rose Main Reading Room. With its profusion of sunlight and carved timber, and its great oak tables burnished by millions of elbows, the chamber expresses the democratization of earthly awe: Even people who live in joyless garrets have a right to grandeur.

While information increasingly lives in the ether, the New York Public Library’s headquarters is an intensely physical place. This iron-and-stone storehouse was built to enshrine knowledge in ink-on-paper form. But temples grow brittle. In 2014, one of the rosettes on the reading room ceiling broke off, failing to kill any patrons only because it happened in the middle of the night. The room closed for renovations for two years. There was also trouble in the stacks, where thickets of iron columns and seven levels of tightly gridded shelves support the upper floors, and where, until recently, 4 million volumes moldered away in a warm, damp fug.

Eventually, the volumes were moved for their safety, most of them to a newly renovated, climate-controlled vault deep beneath Bryant Park. But the old retrieval system endures, albeit in updated form: Whenever a call number is dropped (electronically, now) into the building’s bowels, library staffers — aptly called pages — unearth the requested titles and place them on a miniature train that hauls them up to the surface like hunks of coal from a mine.

4. Grand Central Terminal

Grand Central is rebuilt (twice).

In the mid-19th century, 42nd Street was lined with jerry-built train stations, serving a tangle of competing lines. But by 1869, Cornelius Vanderbilt had bought up enough railroad companies and real estate to build a vast passenger’s palace. His Grand Union Depot opened in 1871, a great glass-ceilinged shed fronted by a brick château. In 1898, the building, now called Grand Central Depot, was overhauled, enlarged, and stylistically reshuffled into a French Renaissance showpiece — but a lethal accident four years later doomed it to instant obsolescence.

In the morning rush hour of January 8, 1902, two trains collided just outside the old depot on the site, filling the tunnel with boiling spray and coal smoke. Fifteen people were killed. The New York Central Railroad decided to switch to electric trains, which didn’t pump fumes into the air and so could run beneath the streets and enter the station from below. That meant demolishing the depot and replacing it with a multilevel terminal. Burying the tracks and decking over Park Avenue created vast quantities of freshly valuable real estate, unbesmirched by coal smoke and protected from noise. The company’s chief engineer, William J. Wilgus, realized that it could pay for an underground station by selling the right to build in the air. That incubated a colossal real-estate deal. Developers flocked to build hotels and apartment buildings that constituted Terminal City. And Grand Central Terminal became one of the world’s most high-tech facilities, dedicated to the era’s great mission: speeding people wherever they wanted to go.

In the rationalistic spirit of the age, the building was engineered down to the minutest detail, merging efficiency with beauty. Hallelujah shafts of sunlight angle through vast double windows and glass-floored walkways, heating the interior and minimizing the need for electric lighting. Early visitors rhapsodized over the ramps from street to tunnel. “The idea,” reported the Times, “was borrowed from the sloping roads that led the way for the chariots into the old Roman camps of Julius Caesar’s army.” To determine their precise angle, the architects made mock-ups and then recruited testers: “fat men and thin men, women with long skirts, women with their arms full of bundles.” The result is a complex of gentle slopes through which people move in a counterpoint of varying tempos. Thanks to that attention to detail, Grand Central was — and remains — one of the modern world’s most exquisitely complex and welcoming public palaces.

5. The Chrysler Building

A monument to the auto industry rises during the depression.

Is there any human activity that architecture can’t elevate? In the early-20th century, the area around Grand Central Terminal was a rough and unglamorous neighborhood, crammed with three- and four-story tenements and businesses that produced an abundance of horse manure. Gradually, narrow-frontage houses made way for hotels like the Manhattan, the Belmont, and the Vanderbilt (later the Commodore) on the northeast corner of 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue. In the great burst of construction around 1930, even those recent buildings came down to make way for skyscrapers: the Chrysler, Graybar, and Chanin buildings and, farther east, the Daily News. The Chrysler Building, an auto company’s monument to itself that functioned as an urban-scale corporate logo, stamped the skyline with the glamour of driving.

It’s hard now to grasp the mixture of misery and dogged ebullience of those days, when a few towers raced glamorously toward the sky just as the U.S. economy was hitting rock bottom. In 1929, the Chrysler Building lunged past 40 Wall Street to become the tallest building in the world — until two years later, when the Empire State Building overtopped them both. The towers’ Art Deco energy emerged from the interaction of aesthetic fancy and legislation. In 1916, as new technologies threatened to turn Manhattan into a dark forest of high-rises, the city began regulating the skyline. The law allowed greater height on wider streets and required buildings to recede as they rose, funneling sunlight to the sidewalk. Hugh Ferriss, the architect whose brooding renderings made him the Piranesi of New York, understood the romance embedded in the new zoning code. “We are not contemplating the new architecture of a city — we are contemplating the new architecture of a civilization,” he wrote. His rhetoric helped transform the zoning code into a spectacularly utopian tool. In 1929, he published his graphic manifesto, The Metropolis of Tomorrow, the book that shaped the dreams of architects, planners, comic-book illustrators, and Hollywood set designers. In a long essay with 108 drawings, he described a city of fantastical drama, in which pedestrians would move around by skyway and towers would have rooftop landing pads.

6. The Daily News Building

The Daily News puts its headquarters on the media’s main artery.

The original plan for the Daily News Building called for a low-rise home for a rumbling printing press that might rattle nerves in a newsroom above but had no sleeping neighbors to disturb. Architect Raymond Hood reimagined it as a skyscraping tribute to the business of asking rude questions of powerful people. It started construction in 1929 and opened in 1931 in a burst of delusional confidence, as if the Depression were just another journalistic opportunity.

The man who paid for it was Captain Joseph Medill Patterson, the left-leaning scion of the McCormick family, which owned the Chicago Tribune. Patterson, a populist idealist, had spent time in England on his way to the front and fallen in love with the Daily Mirror, a cockney-flavored tabloid that kept Londoners supplied with salacious gossip, provocative pictures, and short, punchy stories. He decided to create a similar publication for New York. By 1926, its circulation was well over a million, making it the largest daily in the country. After a few more years of success, Patterson knew where to place a new printing press — on 42nd Street, close enough to the Times that he could beat the competition to the newsstand every day.

Patterson wanted a printing plant with a newsroom on top; Hood charmed him into building a 36-story skyscraper. Hood, like Patterson, was an avowedly practical man for whom money was — in theory, anyway — an infallible guide. In his mind, and in his rhetoric, the News Building was the manifestation of virtuous slide-rule thinking, which held that the most efficient way to design a building was inherently the most harmonious as well. Despite his declared pragmatism, Hood produced an artistic creation, a jazzy concoction of syncopated setbacks and white-brick stripes shooting toward the sky. In a city of flat façades, this was a sculpture to be appreciated from all sides. Hood claimed that he simply stopped the building when he ran out of floors, rather than capping it with some fancy crown, but in truth the corrugated shell extends well past the roof, hiding the mechanical equipment and defining the top with a straight, sharp horizontal line. Simplicity is not usually simple to achieve.

Like all good architects, Hood knew how to deploy his budget for maximum effect, concentrating all the sumptuousness where people could see it. The relief above the main entrance teems with New Yorkers of all kinds — flappers, construction workers, financiers, a young girl telling off an overenthusiastic dog — and an inscription abridges Lincoln’s aphorism “God must love the common man. He made so many of them.” (The News version includes only the second sentence.) The shiny black-and-brass lobby is even stagier, with its quartet of clocks set to various time zones and its giant globe, symbolizing the paper’s worldwide reach. The News eventually abandoned the building (and many of its global ambitions), but so completely did Hood’s design capture the urban drama of journalism that his tower had a starring role in the 1978 film version of Superman, playing the headquarters of the Daily Planet.

7. Tudor City

One developer sees a middle-class oasis where once there were slums.

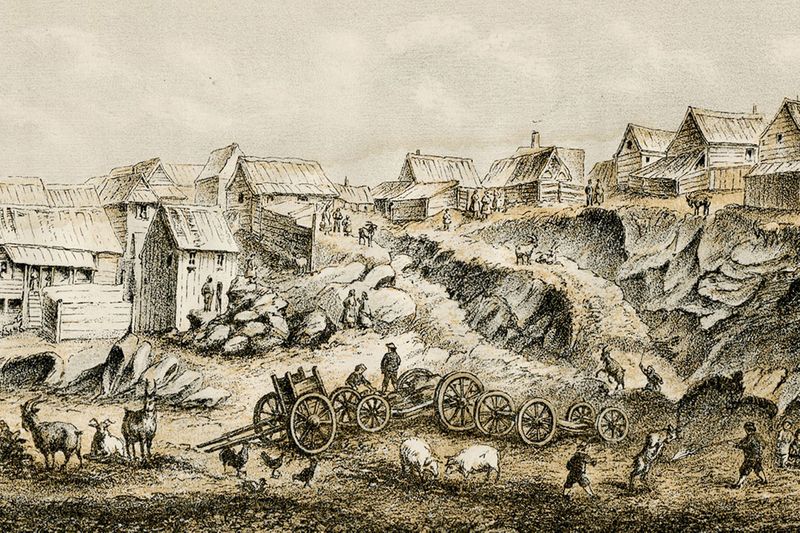

Walt Whitman, gazing east from the ramparts of the Croton Reservoir in the 1840s, imagined an orderly grid of private houses popping up as the city expanded, but the reality was more chaotic. A 1988 Landmarks Preservation Commission report, usually a dry research document, indulged in a vivid description of the afflictions of the neighborhood around East 42nd Street: “Bracketed to the west by the noisy Elevated Railroad and to the east by noxious abattoirs, meatpacking houses, gas works, and a glue factory, the area … had, by 1900, become a slum inhabited by ethnically diverse immigrants.”

Enter Fred F. French, a brawny Bronx kid who had dropped out of college and eventually became a bona fide mogul with a mantra that he’d rather make a small profit on a large business than a large profit on a small one. And the biggest real-estate business of them all was Tudor City.

Launched in 1925, Tudor City was the largest residential complex in the country. It was also a control freak’s fantasy, a hilltop enclave of 11 buildings with 2,800 apartments — practically a manufactured town. It boasted its own streets, hotel, a slightly cramped but fully operational 18-hole golf course, and two parks, each with a romantic gazebo. In building it, French placed the high-yield, high-risk bet that has enriched — or, often, impoverished — developers in every generation: He believed that middle-class people would choose to live in the city, rather than migrate out of town, so long as they could keep urban squalor and chaos at bay. He promised working stiffs an affordable bucolic refuge that didn’t require a long commute.

French fitted out his buildings with modern efficiencies (like refrigerators) and architectural flourishes evoking the days of monarchs in wide collars and rich brocades. Carved griffins, stained-glass windows, and ornate lanterns turned the oversize brick boxes into middle-class castles. The strategy worked. The development was stupendously successful, despite tiny apartments with almost no eastward-facing windows. Enjoying a river view would have had a disconcerting downside: a vista of charnel houses and the stench of blood and offal drifting in from neighbors like the Butcher’s Hide and Melting Association.

Today, the abattoirs, the el, and the slums are all gone. Tudor City’s claustrophobic layouts and phone-booth kitchens keep prices contained and children scarce. Though the city has evolved around it, a verdant retreat in midtown Manhattan still seems like an incongruous apparition.

8. United Nations Headquarters

The U.N. is built on a slaughterhouse that used to be woodland.

The U.N. occupies a cluster of structures, but the Secretariat, the hive of diplomacy’s worker bees, is the international body’s contribution to the New York skyline, a big glass brick standing upright on the edge of Manhattan. In the 18th century, it was Turtle Bay Farm, a wild patch of woods and ravines that sloped down to a bucolic cove. Then came industry: ironworks, coal companies, slaughterhouses, and breweries, which needed access to the river for transportation and dumping. Until the 1940s, the eastern end of 42nd Street had to be one of the least appealing corners of the city. It shot between the cliffs of Tudor City, passed First Avenue, and terminated at the Veal & Mutton Co., a vast terrain of organized slaughter in the shadow of a Con Ed power plant’s smokestacks.

After World War II, the United Nations came into being, and among its first tasks — before the partition of Palestine or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights — was to shop for real estate. A scouting party examined various other sites, including the suburbs of Philadelphia, the Presidio in San Francisco, Fairfield County, Connecticut, and the site of the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens. But it was eventually decided that only Manhattan embodied the U.N.’s ideal of vigorous optimism. John D. Rockefeller, in a supreme gesture of noblesse oblige, offered to buy the reeking acres of riverfront from a local developer for $8.5 million (roughly $103 million today — still a spectacular bargain) and donate it to the organization. Wallace Harrison, Rockefeller’s architect — he had worked on Rockefeller Center and would later collaborate on Lincoln Center — helped broker the deal and hand-picked an international troupe of modernist architects to design the compound, taking for himself the role of ringmaster. Many contributed, not least two squabbling geniuses, the Swiss-French guru Le Corbusier and his Brazilian counterpart Oscar Niemeyer, who fought over the shape, number, and orientation of the buildings, whether the glass-curtain wall should include a sun-shading grid of stone, and — most ferociously — who got credit for what. The cocktail of haste, diplomacy, vanity, and genius might have yielded an architectural hangover. Instead, it produced the first monument of postwar modernism. Many critics found the complex soulless and its creators deluded in the idea that World War III could be averted by orderly administration. “If the Secretariat Building will have anything to say as a symbol, it will be, I fear, that the managerial revolution has taken place and that bureaucracy rules the world,” wrote Lewis Mumford in The New Yorker.

By 2010, the Secretariat had devolved into a decaying time machine. Rain seeped around ancient windows and leached asbestos from crumbling ducts. The lobby’s green marble walls sported the lovingly designed but now culturally unsuitable ashtrays. Architecture that once promised a more perfect world had now seen better days. A $2.1 billion overhaul begun in 2008 restored the original spare elegance. The Security Council’s 60-year-old chairs have been reupholstered in bright Naugahyde, water stains have been cleaned off limestone and marble panels, and decades of nicotine have been scrubbed away from buffed terrazzo floors. All the cosmetic improvements are icing on a high-risk rescue of a creaky modern landmark. When crews began removing the Secretariat’s exterior glass curtain wall, they found that it was barely hanging on. Windows were just a bad storm away from popping off. Then, in October 2012, Hurricane Sandy pounded through New York, causing $150 million in damage. It might have been easier — and possibly cheaper — to demolish everything and build anew. However, for an organization where precedent and symbolism govern every handshake, the historical meaning of the U.N.’s architecture still resonates.

9. Ford Foundation

A foundation trying to save the world replaces a hospital for healing vets.

Along 42nd Street, one kind of civic ambition regularly forces out another. The construction of Grand Central displaced the New York Hospital for the Relief of the Ruptured and Crippled, the predecessor of today’s Hospital for Special Surgery. In an era of often-brutal medical intervention, the hospital specialized in gentler therapies: “sunshine and fresh air, along with diet, exercise, electrical stimulation, and gentle rehabilitation, known as Expectant Treatment.” In 1912, it moved toward Second Avenue and remained there until 1955, when it cleared out again to make way for the Ford Foundation, which was completed 13 years later.

Designed by Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, it, like other mid-century office buildings, is made mostly of glass. But with its sunset-colored granite piers and weathered steel beams, the Ford Foundation has an imposing look of perpetuity. The foundation’s mission is to battle the full panoply of timeless injustices around the world, and its home base is a see-through fortress, braced for an endless war.

Today, green design is often a checklist of energy-saving features that soften a building’s environmental blow. Roche, however, created a work of environmentally sensitive architecture before the term had much currency. During business hours, anyone can step out of the cacophony of 42nd and into an indoor Eden. Walkways thread through an almost preposterously lush bower, designed by the landscape architect Dan Kiley (and closed in 2016 for a two-year renovation), which was meant to inculcate a sense of serene, almost monastic community in the foundation’s pencil-wielding professionals. “It will be possible in this building to look across the court and see your fellow man or sit on a bench and discuss the problems of Southeast Asia,” Roche predicted before construction had even begun, and he was right.

Ford gave up substantial floor area for the sake of trees, light, and air. That sacrifice made the building itself a magnanimous gesture, a gift of greenery to a city that has always been invited in to enjoy it. Part Victorian greenhouse, part modernist Crystal Palace, part corporate plaza, the landscaped atrium was a powerfully original idea, even though it later became a cliché. What better place to end a tour of civic aspiration than in this humanistic gathering place that distills 42nd Street’s dewy idealism?

This piece is adapted from Magnetic City: A Walking Companion to New York, to be published by Spiegel & Grau on April 18.

*A version of this article appears in the April 3, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

Design and development: Jay Guillermo, Terri Neal and Ashley Wu