The Environmental Protection Agency hasn’t released new rules protecting America’s children from lead poisoning since 2001. The EPA has, however, determined that its previous standard was too lenient — turns out, it takes a lot less lead to mess up a kid’s brain than we’d previously thought.

The Obama administration acknowledged the need for new restrictions on the lead content of paint, dust, and soil in 2011. But it never actually did anything about it. In fact, the EPA didn’t even set a timeline for when it planned to address the issue. Notably, the National Association of Home Builders, and other powerful lobbies, have historically opposed efforts to impose tougher regulations on lead paint.

Public-health groups, meanwhile, decided to try to force the government to stop dragging its feet, asking a federal appeals court to rule that the agency had delayed the new rule unreasonably. The Trump administration responded by informing the court that it needed another six years to develop new lead standards (ostensibly, the White House felt entitled to procrastinate at least as long as Obama had).

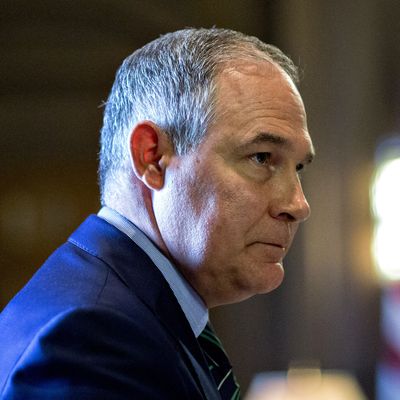

But on Wednesday, the court ordered Scott Pruitt’s agency to propose a new standard within 90 days, and to finalize that new rule no later than one year after that. In a 2-to-1 ruling, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals found that “the children exposed to lead poisoning due to the failure of E.P.A. to act are severely prejudiced by E.P.A.’s delay.”

“Indeed E.P.A. itself has acknowledged that ‘lead poisoning is the number one environmental health threat in the U.S. for children ages 6 and younger,’” the ruling noted. “We must observe … that E.P.A. has already taken eight years, wants to delay at least six more, and has disavowed any interest in working with petitioners to develop an appropriate timeline through mediation.”

A 2016 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that even miniscule differences in childhood lead exposure can have a significant impact on educational performance. Researchers examined the test scores and lead-exposure levels of children who benefited from a housing remediation program in Rhode Island that removed lead from their homes, along with those of children who did not. They found that a single microgram increase in the amount of lead in a child’s bloodstream correlated with a one-point drop in reading comprehension, and 2.1 percent increase in the probability of that child lacking proficiency in math. By contrast, a single microgram decrease correlated with higher test scores and proficiency in both math and reading.

The human costs of exposing millions of American children to a brain toxin are obviously profound. But investments in removing — and more aggressively regulating — lead also make sense from a purely economic perspective: The costs of childhood lead poisoning to productivity, health care, and public safety are so massive, “each dollar invested in lead paint hazard control results in a return of $17–$221 or a net savings of $181–269 billion,” according to a 2009 study published in Environmental Health Perspectives.

Yet, the Obama administration never got around to issuing tougher standards. And the Trump White House was prepared to do the same. Now, barring an appeal to the Supreme Court, the EPA will (finally) take action early next year.