Amid the fairly large swings in the congressional generic ballot over the last three months, the odds of a Democratic takeover of the House have gone from very high to shockingly low to reasonably strong. As Nate Cohn notes, over the long term Trump’s approval ratings and the corresponding congressional polls have been relatively steady. It just doesn’t feel that way, given the wild gyrations of daily political news, reflecting in wildly gyrating short-term polling data.

The topic that’s received less attention over the last few months is the landscape for U.S. Senate races. Originally (and properly) understood as terrible for Democrats, who hold 26 of the 35 seats up in November (or now 26 of 36 if you add in Mississippi’s special election), the landscape at first offered Republicans hopes of gaining a filibuster-proof 60 seats, particularly after Donald Trump carried ten states with Democratic senators facing voters in 2018.

But Trump’s low popularity during his first year in office, along with relatively high approval ratings for Democratic senators, made Democrats more optimistic as the midterm election year approached. And when Republicans unaccountably lost a Senate seat in Alabama in December, the path to a Democratic takeover of the Senate looked suddenly very real, particularly when combined with the likelihood of a second Senate election in blue-trending Arizona and the recruitment of a formidable Democratic candidate in dark-red Tennessee.

But even as Democratic optimism grew, there were signs of gradual erosion in the position of Democratic senators in states not only carried by Trump but carried very heavily.

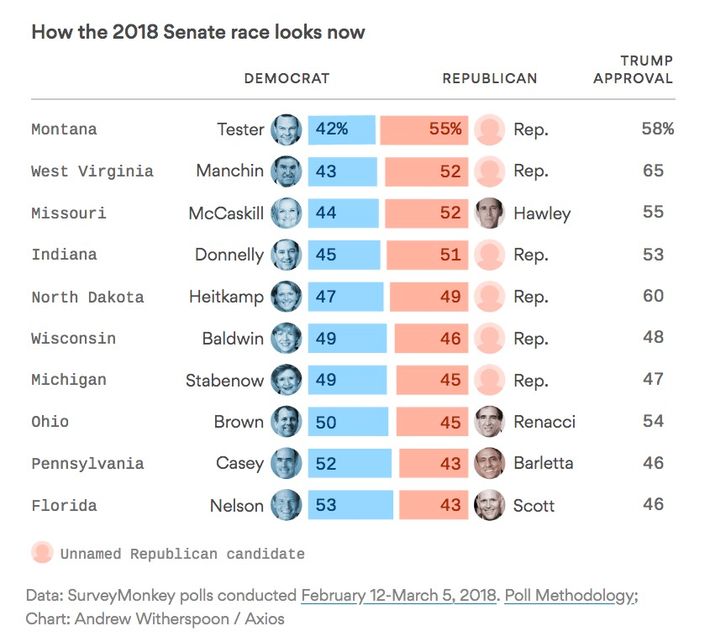

Now we have some directly relevant data about the ten Democratic senators from Trump-carried states in the form of head-to-head trial heats as measured by SurveyMonkey for Axios in online polling from mid-February through early March. Where no clear Republican favorite in a given race has been identified, incumbents were tested against generic (unnamed) Republicans.

At this point, four of the “Trump Ten” senators are trailing generic opponents, and one (Claire McCaskill) is trailing a named opponent (Josh Hawley). Unsurprisingly, Trump’s approval ratings in all five states are in the 50s or 60s (as compared to 43 percent nationally, in SurveyMonkey’s high-but-not-wildly-so assessment).

“Generic” opposition can be stronger or weaker than an actual opponent; it’s mostly a test of basic partisanship. Heidi Heitkamp’s newly minted opponent, Representative Kevin Cramer, is probably stronger than a “generic” Republican. The assortment of less-than-gargantuan Republicans who are running against Jon Tester may be easier to beat than a “generic” candidate. In other cases (notably Joe Donnelly’s Indiana and Joe Manchin’s West Virginia), Republicans must navigate fractious primaries and then get their act together for November. And Claire McCaskill, who looked toasty six years ago until GOP nominee Todd Akin self-destructed, is a living reminder that you never know what might happen next.

But to borrow Donald Rumsfeld’s famous distinction, there are known unknowns along with the unknown unknowns. We know, for example, that Florida governor Rick Scott is going to spend an obscene amount of money in his likely race against Bill Nelson. We don’t know if it will be enough to overcome Nelson’s relatively strong positioning (according to SurveyMonkey, he’s up by nine points against Scott) in a highly competitive state. We also know that Sherrod Brown has a “populist” profile that might appeal to a significant sliver of 2016 Trump voters. But we don’t know if it will be enough in a state where Trump’s approval rating is over 50 percent. And a big imponderable everywhere is the extent to which partisan polarization and the continuing unpopularity of Congress make it all but impossible for Democratic senators to survive in states like West Virginia and North Dakota. In states less “red” than those, Democratic prospects could depend on a “wave” in Democratic turnout, along with a little luck and a lot of money.

All in all, it’s probably wise to avoid too many generalizations about the Senate races of 2018 at this point. But it’s not too early to place in the back of one’s mind the fact that in 2020 the Senate landscape will be close to neutral, and should tilt blue in 2022.