Italy’s government plunged into crisis on Sunday, sending shockwaves from Brussels to Wall Street. The problem took root in March, when Italy became the latest European country to hold an election with surprisingly disastrous results for the political establishment; the March 4 vote saw mainstream parties on both the right and the left knocked down by a new generation of populist politicians fueled by Euroscepticism and popular frustration over the Mediterranean migrant crisis.

The idiosyncratic, anti-Establishment Five Star Movement finished first with about one-third of the vote, while the League, a right-wing populist/nationalist party running on an explicitly xenophobic anti-immigrant platform, came in third with nearly 18 percent. Although the two parties do not see eye to eye on all issues (in fact, they have opposite base constituencies of poor southerners and rich northerners), they went into coalition together and attempted to form a government.

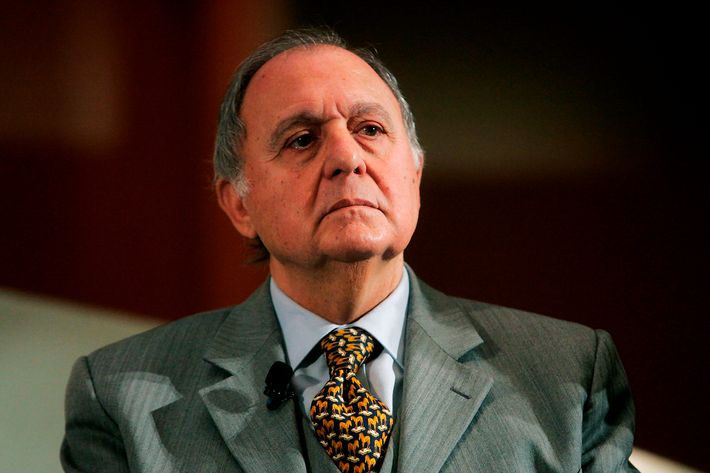

That process was by no means smooth, but eventually the two parties managed to agree on a deal in mid-May. On Sunday, however, Italian President Sergio Mattarella blocked that deal by rejecting their preferred candidate for finance minister, 81-year-old economist Paolo Savona, who has openly advocated pulling Italy out of the euro.

Uncertainty over the country’s future currency was intolerable to investors and mortally threatened Italy’s economy, so Mattarella nixed the appointment. Five Star and the League refused to have a government without Savona, so this effectively put the kibosh on their deal.

The president then asked Carlo Cottarelli, a former executive at the International Monetary Fund, to form a government instead. The populist party leaders were furious at what they considered a subversion of the will of the voters and have called for protests and even Mattarella’s impeachment. The crisis will culminate in a fresh round of elections sometime in the next few months.

Bond markets, those bellwethers of geopolitical anxiety, freaked out, fearing the possibility of Italy ending up with an even more extreme populist government that would abandon the euro, leave the European Union, or default on Italy’s 2.3 trillion euros of sovereign debt. On Tuesday, the value of the euro sank, yields on two-year and ten-year Italian bonds shot up, and the bond-market riot contributed to a nearly 400-point drop in the Dow Jones industrial average.

Why is a domestic political dispute in Rome rattling markets around the world? Here are some answers to the key questions surrounding this week’s events.

Did President Mattarella overexert his powers?

Technically, no. As head of state, the president of Italy, who is elected by the parliament every seven years, has the power to name the prime minister and to reject ministerial appointments. Under normal circumstances, when a national election produces a clear winner, these are practically pro forma functions. In a more divided outcome, the president does get to make decisions like which party should get first crack at forming a government, and previous presidents have rejected ministerial candidates without causing national crises.

Sunday’s decision to reject a key ministerial appointee on the basis of his ideological stance and effectively abort the Five Star/League coalition government, however, was in some sense unprecedented, as University of Salford politics professor James Newell explains.

In rejecting Savona, the president was really rejecting the coalition’s program altogether by saying that a government with unclear stances on the euro and the debt is intolerable. This has led to recriminations from party leaders accusing Mattarella of orchestrating an Establishment coup — effectively enabling what Newell calls a “propaganda coup” by the populists.

Who is Paolo Savona, and why is the Italian Establishment afraid of him?

Savona is well known as a long-standing critic of the euro and an opponent of Italy’s inclusion in the eurozone, which he has characterized as a German scheme to dominate Europe, and darkly compared to other such German schemes of 20th-century vintage. Italy’s financial institutions, the European Central Bank, and holders of Italian debt fear that as finance minister, the elderly economist would lead the coalition government to adopt policies or demand changes in E.U. rules that could cast doubt on Italy’s commitment to repaying its debt, leading to further downgrades of the country’s credit rating.

Their even greater fear is that with Savona, the Italian government might extract concessions from Brussels by threatening to leave the euro. That could be destabilizing even if those threats are idle.

And they may not be idle, according to Italy’s center-left Democratic Party. They’re already campaigning on what they characterize as a secret plan drawn up by Savona to exit the euro and reintroduce the lira over the course of a single weekend. Savona had proposed this scheme, which he drew up with a team of other anti-euro economists, as a “Plan B” should Italy ever need to exit the currency union in a crisis.

Matteo Salvini and Luigi Di Maio, the leaders of the League and the Five Star Movement, insist they have no intention of withdrawing Italy from the eurozone. League lawmaker Giancarlo Giorgetti told the Corriere della Sera newspaper that while some of their members supported such a move, it was not included in the government program the two parties agreed on earlier this month.

Both parties have spoken ambiguously, however, about where they stand on this issue, and their choice of Savona as finance minister raised concerns that they are more open to ditching the euro than they let on.

Will Italy exit the euro or default on its debt?

Most financial analysts say such radical moves are highly unlikely, even if the populist Five Star/League coalition ultimately takes power. That’s mainly because leaving the euro, which would likely also result in a sovereign debt crisis, would be exceedingly painful for their constituents.

“Many voters, even if they are very unhappy with the status quo … do not really want to leave the euro,” Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank, told CNN Money. “They do not like the thought … that part of their savings may go down the drain.”

Italy’s debt is enormous, at 132 percent of its GDP (twice the ratio of Germany and well above the eurozone average of 87 percent). Some observers therefore see parallels to 2012, when the Greek sovereign debt crisis (along with debt concerns in Italy, Spain, and Portugal) put severe strains on the eurozone. Italy’s economy is ten times the size of Greece’s, meaning the consequences of an Italian default or exit from the euro would be that much more catastrophic.

At this point, however, the market’s nervous reaction to Italy may be more of a speculative panic than a rational response: The yield on ten-year Italian bonds is not yet half as high as it was at the peak of the 2012 crisis, and the Italian populists are not openly threatening default and disengagement to force the country’s creditors to negotiate its debt on more favorable terms, as Greek populists have done more than once in the past few years.

Italy is the third-largest economy in the eurozone, well integrated into the broader continental economy, and far less of an economic basket case than Greece, so Italians have more to lose in the event of such an upheaval. Even if a League/Five Star government wanted to do it, the economic and political price would be very high.

Instead, what analysts fear is that this government would chip away at Italy’s commitment to the euro and the E.U., demanding rule changes and concessions that would put stress on the system. In this version of the nightmare, rather than a sudden break, Italy’s membership in the euro or the E.U. grows gradually more untenable until the event dubbed “Italexit,” or more cleverly, “Quitaly,” becomes unavoidable.

Again, analysts say the chance of these events coming to pass are very small. Then again, most mainstream observers thought Brexit would never happen, either.

So what happens now?

Mattarella is betting that the Eurosceptics will be defeated in the next round of elections due to the Italian public’s fears of losing their life savings in a currency crisis. Cottarelli is not expected to actually govern. If the IMF technocrat manages to form a government at all (already doubtful), it almost certainly will not obtain the vote of confidence it would need to actually make policy. Instead, Cottarelli will serve as a stopgap prime minister until new elections can be held.

If he manages to form a government, those elections will take place sometime this autumn. If he can’t, however, Mattarella will be forced to dissolve the parliament and hold new elections as early as July 29, which some parties are already demanding. The Five Star Movement is projecting confidence that it will prevail, although the latest polls suggest that the League has gained the most ground since the start of the crisis.

Though they’ve yet to be scheduled, the upcoming elections are already being billed as a referendum on the euro. Alberto Mingardi, director general of the free-market think tank Istituto Bruno Leoni, writes at Politico Europe that the president has “chosen the electoral battlefield,” establishing Italy’s relationship with the euro and the E.U. as the stakes for the next round of polls.

Mingardi does not hazard a guess as to which way that referendum will go: On the one hand, the mainstream parties that might stand up for European integration are still as shambolic as when they suffered their stunning populist rout in March. On the other, making the election about the euro will force the League and Five Star to clarify their intentions with regard to the union and the common currency — and voters may not like what they hear.

There’s also no guarantee that the League and Five Star, which are not entirely natural allies, will still want to form a coalition together even if they emerge victorious again — but then, the same is true of the center-left Democrats and the center-right Forza Italia.

Mattarella is clearly hoping that Italian voters, who themselves own 5 percent of the government’s debt, will be sufficiently scared of Italexit’s consequences for their household finances and will reconsider their votes for populist upstarts. Without a charismatic figure analogous to France’s Emmanuel Macron, however, Italy’s center may have a hard time rallying voters around this sensible position, Mingardi suspects.

Whichever way the polls shake out, the outcome will be clarifying for Italy’s future, economics commentator Ferdinando Giugliano argues at Bloomberg — but only if the populists stop playing coy and take a firm position in favor of Quitaly-ing.

“If the Eurosceptics won the day,” he reasons, “they would have the popular mandate to hire the finance minister of their choice” and pursue their anti-euro policies openly. If they lose, investors will get the firm commitment they are looking for from Italy that it won’t leave the currency union. If the populist parties continue to capitalize on their ambiguous position, however, “investors will continue to take flight and Mattarella will still have an impossible job.”