Above: Alex Katz’s revisiting of his 1940s “Subway Drawings” for New York. Read more here.

The city is many cities, that’s the beautiful thing. Everyone builds their own New York, mostly out of the people who surround them. But everyone shares the sidewalks, too. And we trade apartments, sometimes finding someone else’s peroxided hair between the floorboards. We fight over cabs (and Citi Bikes) and close elevator doors on one another. Every busy intersection is a kind of rat-king tangle: chance encounters, drag-out fights, families making their way, transactions and missed connections and hustlers of one kind or another pulling scams of one kind or another on rubes of one kind or another. Which means — look around — that we are always, constantly, starring in one another’s city. Guest-starring, at least. The woman behind the deli counter; the man who bumped into you outside, somehow ruining your day. The person from the subway you’ve been madly fantasizing about since. The one who passed the news to the friend of a friend who later got pinched for insider trading. The encounter in the bathroom of the bar, or the two college kids you watched kiss good-bye at Penn Station who came to mind again years later in the middle of the night. The woman at the dog walk you envy for her beauty; the neighbor you hate for having the apartment with the better view. The intimacies overheard on the street, the bodega-line pickup watched over by the manager. Six degrees of separation can feel like a joke. What connection requires more than three? We live on top of one another.

This anniversary issue is devoted to what might make other people in other places go crazy but here we call connection. Not just the connections we choose, like our poker groups or going-out friends, but those that could happen only in a city as clotted and manic as ours. Fifty years ago, New York’s founding editor Clay Felker wrote a mission statement for his new magazine. “We want to attack what is bad in this city and preserve and encourage what is new and good,” he wrote. “We want to be its voice, to capture what this city is about better than anyone else has.” Here, we return to this mission, attempting to capture the city’s voice through stories that are spoken as much as written, almost entirely in the first person, and always about how our disparate lives intertwine. We realize there are still barriers, of course — moats that divide New York into little islands. The city’s schools are the most segregated in the country, and there are those who rarely leave East New York or the Upper East Side. Nor do we live in a paradise of small talk and getting-to-know-you: Sometimes proximity is dreadful. But New Yorkers who spend their lives here, shoulder to shoulder with one another, cultivate an exquisite talent for close-quarters projection — every stuffed subway car a choose-your-own-adventure of imagined new friends and futures, every commute an excuse to daydream alternate lives.

And eavesdrop. In “The Enormous Radio,” John Cheever imagined a New Yorker tuning in to the sounds of those living stacked around her on all sides — above and below, just to the right and just to the left, a cramped apartment-house honeycomb of urban anomie and gossipy self-consciousness. As everyone who lives here knows, the device isn’t necessary: In most buildings, you don’t need a radio to listen in on the neighbors. And even those blessed with especially strong insulation are assaulted with new voices each time out the door. Inscribed by them, really, as you walk these streets; just open your ears and listen.

My Strangers

“I get, like, panic attacks, on the train especially. That’s why I get into the benzos.”

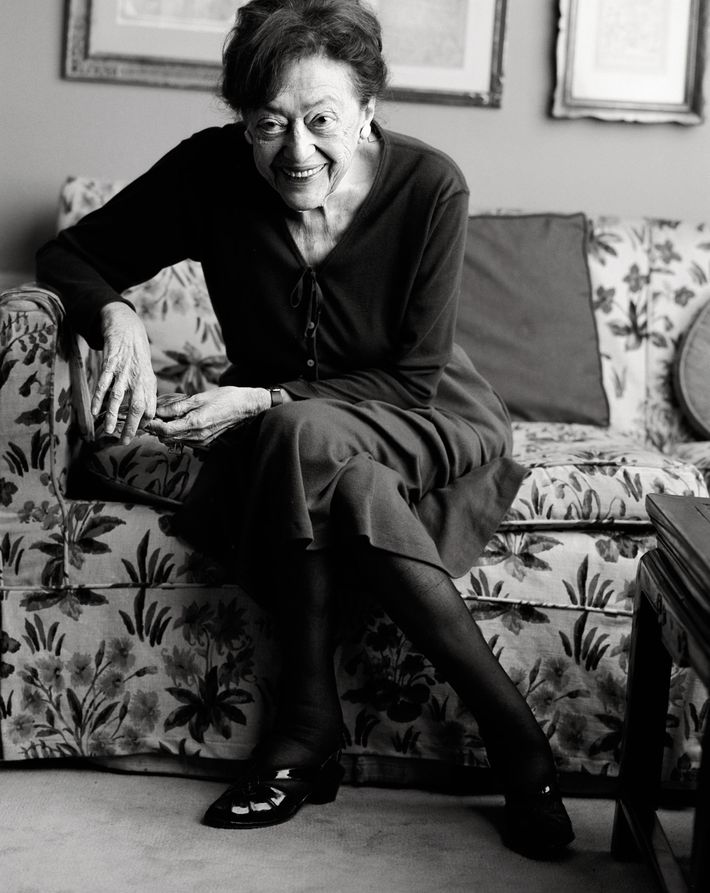

Who’s sitting next to you on the subway? On an R train in September, we asked.

Interviews by Hannah Goldfield

Portfolio by Peter Funch

MY COLLEAGUE

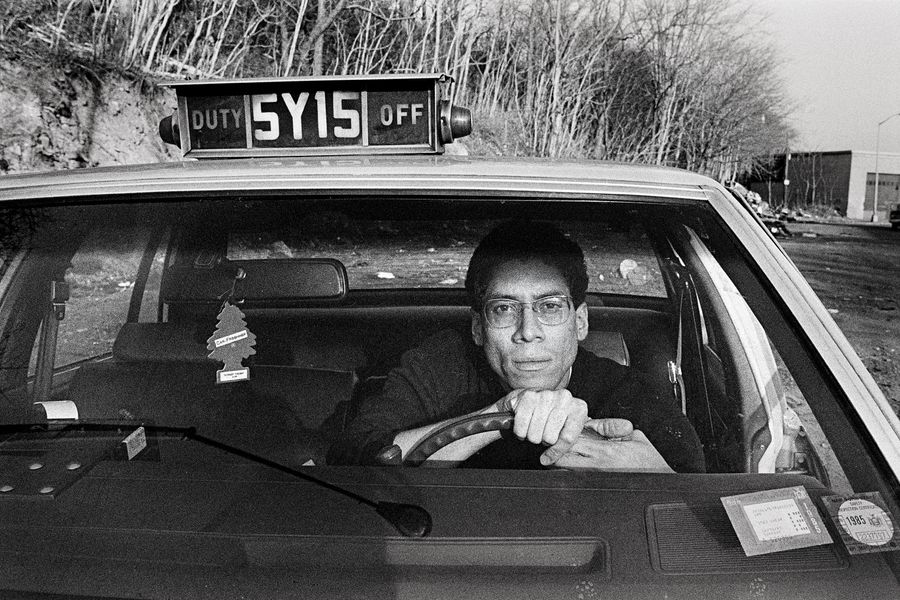

“No other taxi drivers would stop for me.”

TONI MORRISON ON THE SOLUTION TO HER PROBLEM.

“I moved to New York City to take a really splendid job as an editor in a well-respected publishing house. The work was both familiar and challenging. Familiar because I had been a university professor for six years and accustomed to evaluating essays, term papers, fiction, etc. Challenging because I had never worked in a place where the value of writing was measured in sales.

Except for small irritants, living in a midtown apartment was comfortable. All I had to do was get there — which soon became a major irritant. There were no black cabdrivers then in that part of New York, and no other taxi drivers would stop for me. They traded their quick glances at me for profiles of disdain.

One day after work, Eileen, a young white woman, and I were standing on the street corner outside our office building chatting. Although we worked at the same publishing house, she chose her own schedule — one typical of her highly independent life. Having traveled widely to many off-the-grid countries, worked in a veterans hospital, and lived in Brooklyn, she understood New York life quite well. Which is why, when we were standing together, a cab pulled up to the curb.

I got in. She waved.

Solution obvious.

From then on, every day at the end of our work, she would accompany me to the street corner and wait. Cabs screeched toward us. It never failed.

My One-Handed Neighbor

“Look what happened to me here.” Mary told her to get out of the city.

By Eileen Myles

I moved into my apartment 40 years ago. I had this neighbor, Mary, and she was about to go. I don’t think I got her apartment. I think she was across the hall. I started on the fifth floor and moved down pretty quick to the third but I think she had been up there on the fifth, one day she invited me in. The building faced a forest of ailanthus trees. We called them sumac in Massachusetts and regarded them as junk, what grew behind the dry cleaner’s, etc. But that was New York as it turned out and we had so many of them back there it looked like a jungle. It was pretty wild but I’m mentioning it because the jungle was bright green, filling the windows where she stood. Now I’m sure Mary was on the fifth floor. She was in the back where the trees grew and I was still in the front, facing the street. In my building you wanted a back apartment like she had and that’s where she stood and told me her story, which I’ll never forget.

Mary had a hook instead of a hand. She was a dancer and she said it like she was no longer a dancer. She had gone to do her laundry at the place on 6th Street and First Avenue and by now that laundry is gone. It was very unslick-looking like lots of the businesses seemed then. Like somebody had built this laundromat, nailed wood and painted it. It was something kids made, but they were adults and it was the world, New York, which at the time to me was still a new place. This is in the ’70s, 1977, to be precise. So, as she told her story she shook her hand at me, which was a hook.

Apparently, she had been doing her laundry in that laundromat on First and I think when she stuck her hand in the machine to get out her wet clothes the machine started up again and somehow it cut off her hand. She was very angry about the incident. She was a small woman, she was a dancer she told me more than once, and it was such a performance she was giving me with the bright sun of early summer pouring in through her apartment window and all the sumac shuddering out there. I don’t think she was that much older than me. She was a small woman, white, with medium straight hair. I think the incident had occurred only a couple of years ago. She had been waiting for her court case to get settled and I think it just had. She got a lot of money from the laundromat. She was going to get out of here. I mean of course I am going to leave New York she jeered at me and everything. I was a dancer. I know you think of this as new but this building is bad. You really should get out of here. Look what happened to me here. This building is not a good place. It will fall down around you. You have to get out. She looked completely mad. Things like that happen to people in New York I thought. I’d pass the laundromat daily thinking about what it had done. But it was the building she blamed, not the laundromat. It might happen when I’m not home I thought. Always if I’m out of town I think it might happen then. And then I’m back in my apartment on the third floor, where I went, in my bed, just lying there for 40 years, waiting for it to come true.

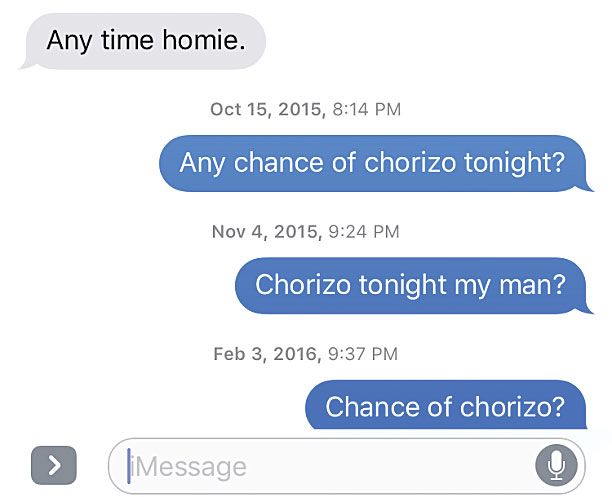

My Three Dealers

“Weed is a white guy who calls me ‘homie’ and greets me by saying ‘Sup?’ ”

Cocaine texts in Hebrew.

For cocaine: M. is from Ramallah. Palestinian-Christian. We speak Hebrew together. Sometimes we text in Hebrew. Sometimes he forgets and slips into Arabic, which I don’t understand. Each time he comes by, he drives a different car. Toyotas. Nissans. A Ford Fusion. All of them are new and black with Uber decals on the windshields. Another change brought about by ride-hailing apps is that, whereas M. used to have me sit up front, as if I were his friend, now he has me sit in back, as if I were his paying passenger. I am. He gives me my bags, takes my money, and drops me off around the block. He has a wife and two kids and is saving up to study “how to work with the environment.”

For weed and MDMA: Z. is a white guy who calls me “homie” and greets me by saying “Sup?” He lives in the basement of a house next to the projects. Each time I’ve gone to him, he’s had a different dog. A different pit bull. One time, he had two corgis, which wouldn’t stop barking and wouldn’t stop trying to climb me. He explained, as if by way of apology, that they belonged to his parents, who were away for the summer. “They’re fucking crazy,” he said, and it took me a moment to realize he meant the corgis, not his parents. “Fucking dogs have never been out of Westchester.”

For prescriptions: Dr. T. is a doctor. A real one. He went to real schools. He has an office off Park Avenue. Diplomas on the walls. He doesn’t take appointments. Rather, you just call or text him to check if he’s in. He’ll write you a script for anything. Then he’ll talk about yoga: conflicts with his teachers, crushes on his fellow students. I enjoy the conversations. I enjoy telling him, “You have issues with authority,” and “You should definitely get her number and take her out.” Though I can’t quite shake the feeling, when I’m getting up to leave, that I should be getting my drugs for free in exchange for psychological counseling.

—An unnamed novelist

My Fellow Cadets

“Colonel has no limits on sugar. And he doesn’t have kids, so he doesn’t know what a bedtime is.”

After school, the Upper East Side Knickerbocker Greys practice drills and drink Shirley Temples.

Ben Miller: When we go to the Players Club, we’ll go in uniform, and we drink and eat and play pool.

Michael Kourakos: Shirley Temples.

BM: I personally don’t like them. But a lot of people do.

MK: Too sweet?

BM: Too sweet.

MK: I drink four. Or two.

Garrett Ward: I usually get five or more.

BM: Also, the Players Club is a chance to get away from our parents, and Colonel has no limits on sugar. Well, some limits. He doesn’t have kids, so he doesn’t know what a bedtime is.

Aiden Eyrick: He also lets us go about the pool table as we like. I’m not very good.

GW: I usually just hit the table with my pool stick.

AE: I’m not bad, but Michael’s definitely better.

BM: We talk about what we’re doing in school. Current events, maybe.

AE: And if one of Colonel’s friends or associates comes over, we’ll tell them about our grades. I act in a refined manner. Look them in the eye.

BM: Shake their hand.

AE: Make sure you make a good first impression.

—As told to Katy Schneider

My Dad

“My brother-in-law always says, ‘There are only two stories in the media: Build ’em up, tear ’em down.’ ”

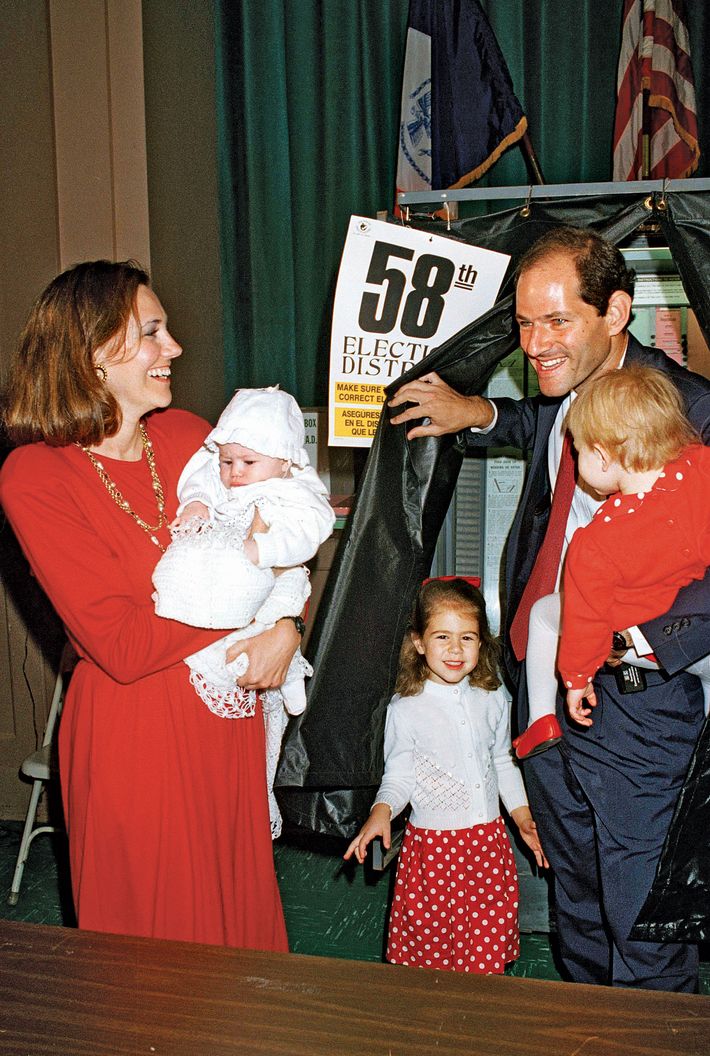

Eliot Spitzer on the father who wouldn’t let him quit.

“In 1994, when I decided to run for office, the gut check was really my dad, who knew nothing about politics. He was the shtetl kid who went to CCNY, did well, understood success was a great thing, but “use it for something.” So he was thrilled. After I lost in ’94, he said, “You’re not stopping now. Of course, that’s up to you — you can go back to law, you can come to the family business. But you’ll be bored for the next 30 years. Politics is exciting, dynamic, challenging. Keep at it.”

Oh, sure, I knew I was making some significant enemies as attorney general. Hank Greenberg is still suing me! But you know what? We were right. I wouldn’t change a single thing we said or did about Wall Street. I’ve never criticized them for trying to attack me. That’s their First Amendment right. Now, some of the things they did were more than criticize. Silda always used to say, “It didn’t turn out so well for Don Quixote.” I said, “Ah, the book was too long, I didn’t get to the end.”

I was elected governor with a very significant majority. I wish we had played certain issues differently, not moved as quickly. It cost a lot of political capital. We did quite a fair bit, though. We were right about driver’s licenses for the undocumented. We got a great first budget, and then something switched with Joe Bruno. He was the Republican leader of the State Senate and didn’t want our agenda to succeed. Joe was an impediment.

We would have taken back the State Senate for the Democrats in ’08, and then we would have been able to implement an agenda. We’d actually turned the corner by February of ’08, when my, you know, the other stuff forced me out of office.

Who was hardest on me but stuck by me? Probably my dad, who didn’t want me to resign. His attitude was “In the scheme of life, you have a mission to do. Go out, stand up.” But I still believe I made the right decision, given the politics. I don’t blame the media, because that’s what the media always has been. Its purpose isn’t to elevate us morally. It is to inform, it is to entertain, it is to needle, it is to bring down the powerful. My brother-in-law always says, “There are only two stories in the media: Build ’em up, tear ’em down.” I was treated as fairly as anybody else. Moments of self-pity are wasted time. There were reporters who turned on me, sure. No, I don’t want to name any of them. They’ll find out. That was a joke.

Yeah, other politicians or public figures have reached out to me when they were in trouble. I’m not going to tell you who they are. People call and ask, “How do you make it through?” I tell them, “Sit down and realize it’s gonna get better. Turn off the TV. Don’t look at the headlines. Those pass. I don’t care whether it’s shark bites or kneeling at the national anthem — next Monday, the story will be different. What’s more important is, how are your kids? How’s your spouse? Are you going to keep that together? What are you doing next?” That’s what matters.

It will be ten years in March that I left Albany. How do I make sense of it now? I’m not sure you do. You can’t make sense out of everything. You keep moving forward, you try to do useful things and build a useful life. It doesn’t mean you don’t look back with enormous regret. Enormous regret. But that’s not always a useful way to spend too much time. I give myself five minutes a day. That’s it. Four minutes would be healthier.

I’m a builder now. Most of what my dad built was on the Upper East Side, because that was the heart of the city. Now it’s Brooklyn. We have a site under construction on Kent Avenue in Williamsburg. As a lawyer, as a prosecutor, in politics, there’s a lot of talk. Occasionally things happen. When you’re building, you actually see concrete being poured and curtain wall being applied to the façade. It’s enormously satisfying. I hate to sound like Ayn Rand, but there’s something very rewarding about that tangible productivity.

—As told to Chris Smith

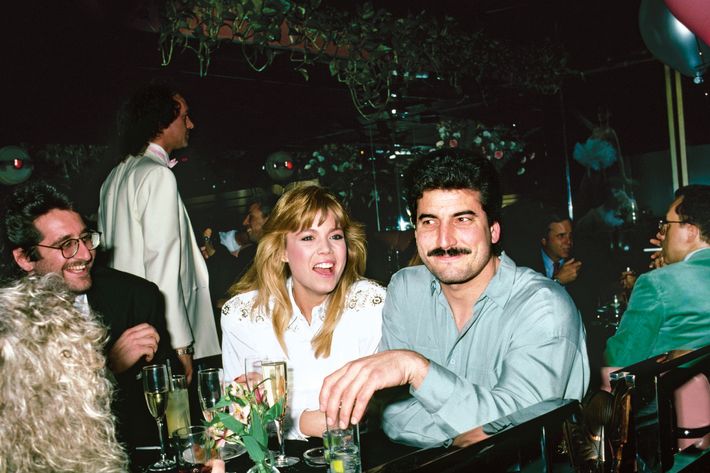

My Fellow Drunks

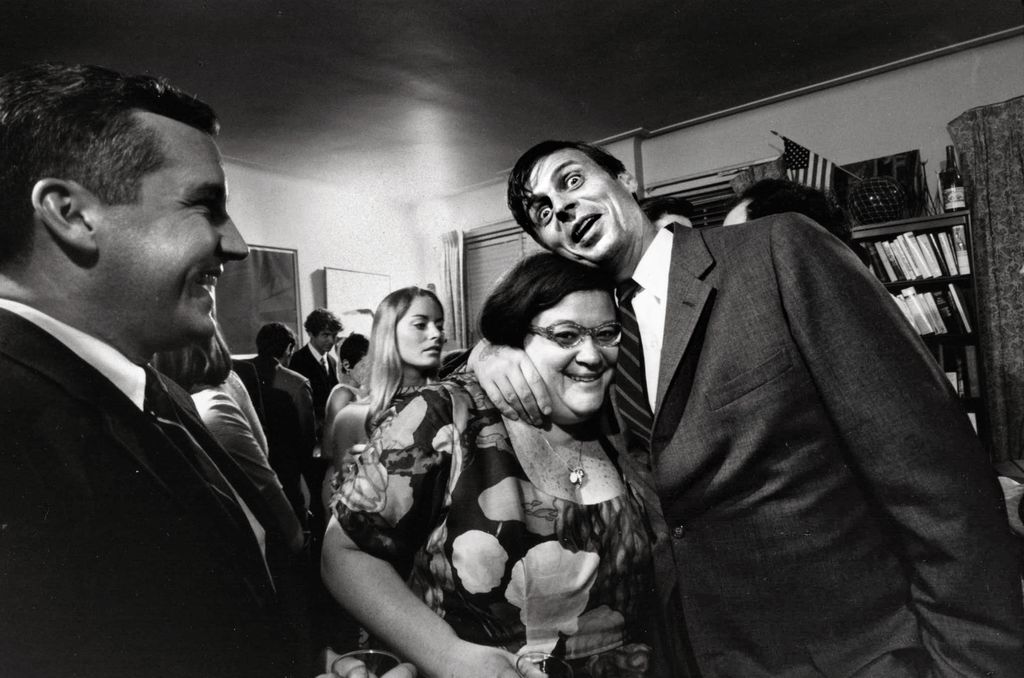

“ ‘Why did you read that one?’ Norman Mailer asked. ‘I wrote it in a weekend.’ ” How I became good at literary parties.

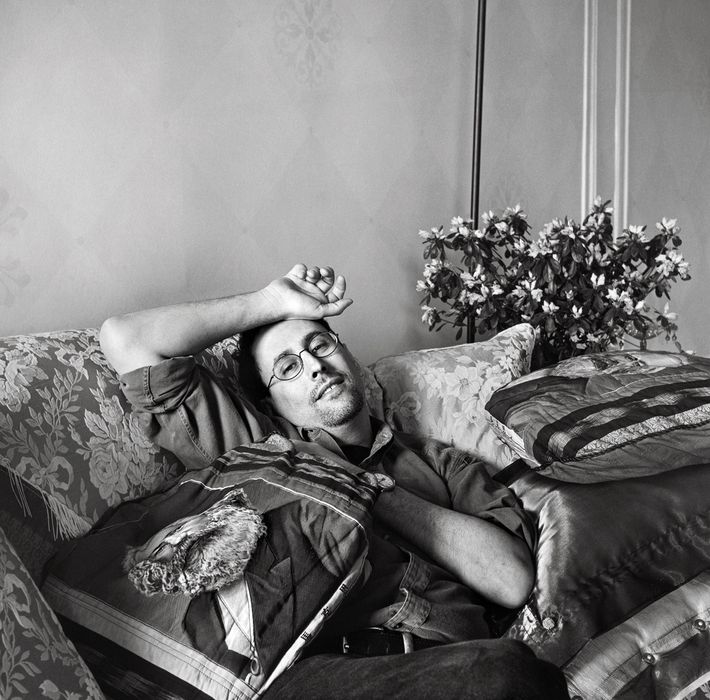

By Christian Lorentzen

The first time I visited New York after turning 21, it was for a party at George Plimpton’s house. I’d only ever been inside one other Manhattan apartment before. Norman Mailer and Lou Reed were there. My best friend told Mailer he’d just read his novel Tough Guys Don’t Dance. “Why did you read that one?” Mailer asked. “I wrote it in a weekend, for money.” None of my friends had the temerity to talk to Lou Reed.

I found myself engaged in mutual elbowing with a man about my height in the crowd advancing on the bar. It was Plimpton. He got his glass of Dewar’s on the rocks and I my cup of wine. I put my cup on a table, lit a cigarette, and told Plimpton that his book The Curious Case of Sidd Finch — about a pitcher from the Himalayas with a 168-mph fastball — was the first novel I’d ever read. “What are you reading now?” he asked. I was reading Swann’s Way. “Well, then I pointed you in the right direction.” I picked up my drink and took a swig. It was a bitter slosh of cigarette butts and ash. Wrong cup.

Parties are a crucial part of the equation in publishing. The little magazines introduce the talent first, and parties are the way they draw in readers and sell issues, reward the grunts who do the (usually free) labor, and create an aura around their editors. Writers do their work in solitude, but it’s sometimes good for them to get out, too, even when it’s only among kids who will fawn over them. It’s at parties that they play the role of Writer, acquiring allies and rivals. They might even pick up material, an idea, or at least a notion of what not to write. In his notorious memoir Making It, Norman Podhoretz said it was parties and the prospect of talking about their pieces at parties that made writers get their pieces written. After his book came out and all his friends trashed it, he started drinking alone. Then he became a Republican.

Minor humiliations, like vaccines, are important for young writers, and I made it back to Plimpton’s house a couple of times after I moved to New York. It was there that a novelist mentioned he’d noticed a recent long essay about the Albanian novelist Ismail Kadare. I sensed that this was my chance. “I wrote that!” The novelist said nothing and walked away, which I see now was entirely appropriate. My anointment would have to wait.

In those days, I only knew one guy with a cell phone, and he had a mild obsession with Plimpton. He made his way into Plimpton’s study at one party and called himself from the phone to get the number. A few times over the next couple years, he’d call Plimpton in the evening to gauge his interest in sitting on panels he was setting up — events that were entirely fictional. We knew Plimpton’s assistant in those days, and she put a stop to this. “When you called last night, George was on the phone with Muhammad Ali and had to put him on hold for ten minutes!” My friend was bereft when he lost the phone with Plimpton’s number. But it turned out George was in the White Pages.

Open City threw the downtown parties, the cool ones. McSweeney’s was still run out of Brooklyn when I hit town, and I remember lines around the block at Galapagos in Williamsburg for the launch of issue No. 5, the number with the long brilliant story “Mister Squishy,” by Elizabeth Klemm, a one-off pseudonym for David Foster Wallace. A friend of mine got drunk that night and had all the readers sign the Kurt Vonnegut novel he had on him. What’s the market value of a copy of Slaughterhouse-Five signed by Dave Eggers, Sarah Vowell, and John Hodgman? The drunk guy runs a corporate-publishing imprint now.

Once I had a real job as an editor at a magazine with a staff of three, no website, and few readers I knew personally. I spent some of my off-hours helping my friends start n+1. I was a “consultant,” and besides showing them how to make a table of contents, proofreading, finding them designers, and writing movie reviews, I tended bar at their parties. I met all my friends that way. The first time the mag tried to make real money off a party, with rich people there, somebody stole the cash box. There was a rumor it was used to start another magazine. At least that was the hope.

The best friend I made from going to lit parties was Matt Power. He was a journalist and an activist, had lived in a squat in the Bronx and with the Flux Factory collective in Queens, rode a motorcycle, and flew all over to write his pieces. At lit parties, whenever Matt met a fiction writer, he’d mention that he’d dropped out of the Columbia M.F.A. program because he thought true stories were better than what he could make up. I would roll my eyes and interject that style was the only thing that really mattered. Matt always wanted to crash New Yorker parties to meet his globe-trotting heroes, but I thought you shouldn’t go to their parties if you didn’t write for them. Still, we crashed a few. In general, I learned, you should stay away from parties for rich people, because their purpose is donations and having a good time is secondary. Never go to a networking event. Poetry readings are either the best or the worst things. You can skip any book party because they only happen once, they end too soon, and there’s no narrative to them, especially if you’re not there. I’ve only been to one really good one, for Jon-Jon Goulian’s The Man in the Grey Flannel Skirt, at the Wooly. Things got messy, somebody got sick, and I almost got into a fistfight. That was all after Bob Silvers left. The best way to befriend famous people is to have no idea who they are.

Today, Open City is gone, and McSweeney’s is elsewhere. New magazines flare up all the time — Triple Canopy, Gigantic, The New Inquiry, Jacobin, Adult — and transform the landscape, transform what it means to be a magazine. After George Plimpton died in 2003, the offices of The Paris Review moved to a Tribeca loft. Same party, new shape. One night Lorin Stein and I were busted for smoking on the fire escape. A no-no with the neighbors. Lorin is the editor now, and he moved to another loft in Chelsea. An eminence will occasionally appear, Vivian Gornick or Ishmael Reed or Frederick Seidel. I go to see old friends. I’m the little brother of the older crowd now. Matt died of heat stroke on assignment, walking the Nile, in 2014. I still read his stuff. I still miss him at every party.

My Competition

“I had to say the line ‘Agent Willis, look at this funny little finger.’ ”

Six actors auditioning for the same ‘House of Cards’ role (“Father”).

Kevin Isola, 47

“I said the line ‘Agent Willis, look at this funny little finger.’ Kind of a miracle that I got that out with a straight face. In the morning, I took a ‘butter bath,’ which is what it sounds like. Drop in three sticks of butter, a bit of heavy cream, some raisins, lather up; you’re good to go. Makes the skin look great and relaxes the muscles.”

Kohl Sudduth, 43

“On my train ride, I tried to immerse myself in the world of a deeply traumatized man. How would he experience the cacophony of the subway?”

Zack Robidas, 34

“I kept thinking about my pit stains. It was unusually warm for October, and the train was a nightmare. I was rushing around and sweating profusely. I didn’t get cast. I blame the sweat.”

Richard Thieriot, 38

“The only line I remember is ‘Then where are they? Where are they?’ And I only remember it because I was overacting it. Maybe an accent would have helped.”

Joe Carroll, 27

“I’m not sure how much I can give away, but let’s just say there was a scene that really hit hard with something going on in my home state. It was emotional and easy to connect to.”

Matthew Montelongo, 44

“After determining that everyone else in the waiting room was better looking and more talented, I tried my best to tune them out.”

—As told to Trupti Rami

My Salon

“No one is going to barge in on us when we’re unveiled.”

The Yemeni-American friends who get their brows bleached monthly at Le’Jemalik Salon in Bay Ridge.

Rabyaah Althaibani: I met Samia during the campaign — we were both working to elect Reverend Khader El-Yateem for City Council. Samia was this amazing, feisty little hijabi woman.

Samia Aljahmi: I got bunions during the campaign from walking so much. It was a very stressful time. But this place is like therapy for us.

Sarah Alsaidi: They have Muslim services: halal brow bleaching for Muslim women who don’t pluck, because in our religion we’re supposed to look natural, like God created us. But we also want our eyebrows to look shaped.

Aljahmi: And there’s privacy. No one is going to barge in on us while we’re unveiled. Anyway, even if I am veiled, I don’t like people seeing me get my upper lip done.

—As told to Katy Schneider

My Crowd

“Woody Allen comes for dinner. The wife comes for lunch.”

On Sunday nights, the regulars order veal Milanese at Sette Mezzo.

“Co-owner Oriente Mania: Last Sunday, we had Martin Lipton, the Tisch family, the Leon Black family, the Kravitz family, the Steinberg family, the Gristedes, the ex-wife of the former president of France, the Blumenthal family, Larry Leeds, Richard Cohen, Richard Lefkowitz, Bob Jeffrey, the Murdochs, the Lauders. Everyone on Sunday all went to give condolences to the Newhouse family, because they come every Sunday to the same table. Table No. 11, by the window. Woody Allen wasn’t there because he was out of town, but he typically comes for dinner every Sunday. The wife comes for lunch. Joan Didion knows we are really busy Sunday, so she comes during the week with the friend who takes care of her. They order spaghetti with basil and tomatoes and chicken paillard, half an order. Martin Scorsese comes all the time. He orders the veal Milanese, which is fantastic. Al Pacino doesn’t come on Sundays — he comes with Martin Bregman during the week, because he uses a wheelchair, and we already had Si Newhouse with the wheelchair on Sundays.

—As told to Katy Schneider

My Kid

“Nothing Butt Loud Crowded Fun Chicken Korma.”

Children described their city. Their parents made a picture based on those words.

—As told to David Colman

My Tormentor

“I just found her irritating. Conceited! An airhead!”

The issues that surfaced while belly dancing.

By Mary Gaitskill

My experience of envy was the most banal type you can think of, among the most ridiculous and to me initially really confusing. I envied the youth and beauty of a young girl! This is not normal for me. I sometimes envy youth and beauty in a general way, but I don’t often compare myself to specific people, especially not to girls who at this point in my life are in a completely different category.

She was someone I met at a belly-dancing school delightfully called Bellyqueen, which is the kind of intensely multicultural place that is unique to New York City. Some students will plainly go pro, and some already are. Some are performance-addicted amateurs, some are, like me, more casual. Everybody who stays with it does so because they love it, because it is incredibly and deeply fun. I recently told a writer suffering from depression that she should try it, because if you have joy anywhere in you, belly dancing can wake it up. I meant that.

There are many pretty or beautiful girls at Bellyqueen, and most of them I just appreciate. This girl, as I say, was different. I am guessing she was about 20. She was Chinese, tallish, with shoulder-length very black hair and a slender, delicate frame. She did not appear to be an experienced dancer, but she was a natural dancer, radiant and lithe. She had some of the common markers of beauty, as least as I define it: glowing skin; full, finely shaped lips; a soft but sensually heavy jaw; deep-set, heavy-lidded eyes. But what made her irresistible to my gaze was something in the way she moved, a preening exuberance that was sometimes touchingly awkward, as if she were slightly dazed by her own loveliness. Everybody warms up in front of the mirror, but she posed and danced at herself as if she were the only person in the room.

At first, I didn’t even realize that what I felt toward this girl was envy. I just found her irritating. Conceited! An airhead! Mindlessly pleased with herself! Most of the time I didn’t even think words, I just felt that dismissive irritation. I think it took months for me to realize what I was actually feeling, and when I did, that of course made the experience even more irritating — and bewildering. Why, of all the pretty girls at Bellyqueen, of all the drop-dead beautiful girls of my acquaintance in New York, had my psyche chosen this girl to be envious of? Really, I knew that if I looked like she did, I’d dance at myself, too. I also knew that many people would consider her cute rather than actually beautiful. None of that mattered. My irritating envy was like a tiny glass splinter in my foot, the kind of splinter you can only feel when you step a certain way, and which you can’t see to remove.

Then I took a PURE class. PURE stands for Public Urban Ritual Experiment; it is a loose affiliation of artists who aim to promote “community, healing, and social change through dance and music,” a mission that sometimes takes the form of therapeutic workshops, which happen at Bellyqueen with some frequency. These classes (with titles like “Return to Love” or “Reimagining Beauty”) are not strictly belly dance; elements of other dance styles show up, and there is often a therapeutic element — journaling, expressing emotions in movement, revealing all manner of “issues” to a circle of reliably empathetic women. It’s corny, but it’s my kind of corny (yes, I want to “Return to Love”), and so, early on, I decided to try a class. I don’t remember what the class was called, or what it was about, because my memory of it is dominated by the weird fact that she (she needed therapy???) was there, exuding her usual degree of overjoyed self-delight. Most of the dancers there were older (by that I mean 35-plus), and as they introduced themselves to the empathetic circle, they revealed various angers, insecurities, pains, and fears related to self-esteem or “body image.” I thought: If this girl is going to complain about her body issues, my head is going to explode. But when her turn came around she simply and energetically declared, “I am Lu Lu! And I am here to learn about myself!” Inwardly face-palming, I thought, Of course. Of course you are. But I didn’t have time to dwell on it because the instructor was describing the exercises/choreography she had planned and then we were paired up to explore our issues together through dance. Guess who my partner was?

Our first exercise was for each to mirror the other in an improvisational dance. I had never looked Lu Lu directly in the face for any length of time before, and when I did my irritation … evaporated. This was partly because I was busy focusing on what we were doing together; it was also because it was impossible to feel irritated by what I suddenly realized was a quite guileless and tender face. Then came the second exercise, which required us to stand hip to hip, shoulder to shoulder, and put our arms around each other. Almost immediately on touching her I felt something that completely contradicted my idea that she was a shallow, narcissistic twit of whom I was senselessly envious.

To explain: I have an ability that I am guessing many people have, that is, the ability to sense another person through touch. This doesn’t happen every time I touch someone, but when it does, I pay attention. My physical sense of a person may not always be right, it could be shaped by fear or desire or something else. But experience has taught me to trust this tactile understanding, especially when it contradicts what I thought I knew or had assumed. What I felt through touching Lu Lu is hard to describe except that it was wonderful: gentle, truly sweet, somehow sparkling, like a soft landscape at dusk with the fireflies just out. Inner beauty: Yes, I think that is what it was. I don’t remember what we did in terms of movement, only that it felt a little like falling in love, not erotically but emotionally. And that when it was over I took her hand and said what I had probably always wanted to say (for I believe that people always desire to say what they most truly feel): “Lu Lu, you are so beautiful!” And she replied — of course! — “You are beautiful too, Mary!”

When I repeated this exchange to another dancer, she deadpanned: “Yeah. I can just see it.” By which I thought she meant I was making a big deal of nothing or maybe that I’d taken PURE’s message a little too much to heart. Maybe. But if nothing else, I realized what I had actually been envious of: the girl’s undamaged inner beauty, which I believe was the most real thing about her, even if she was perhaps also vain or even shallow. I didn’t become friends with Lu Lu after that or even have a conversation beyond friendly greetings. A 40-year age difference is pretty significant, and I don’t know what we would’ve talked about. But I never felt any irritation with her again, or even real envy. I felt warmth. I still do.

My Rich Clients

“In 1978, I sold the first co-op for $1 million, to the Bolivian tin king.”

A. Laurance Kaiser IV, a real-estate broker, coined the term “triple-mint.”

“I just turned 76, and I’ve been a broker for 51 years. When I started, there were only seven or eight firms, and everybody knew each other. Now everyone is part of a “team,” where one person shows the apartments and another negotiates, like an assembly line. I studied the buildings on Fifth Avenue. I could walk a client from the Sherry-Netherland at 59th Street up to 97th Street and point out building by building: That one has summer work rules; that one, you can’t put in air-conditioning because it will freeze the outside of the building; this building might have an 11-room apartment for sale, but most of the rooms are on an air shaft. I can do the same thing with Park Avenue.

The first apartment I sold was the apartment of the niece of Averell Harriman, at 955 Fifth Avenue. I don’t remember how much the buyer paid, but it was 50 years ago; it couldn’t have been much. In 1978, I sold the first co-op for $1 million at 834 Fifth Avenue, apartment 8B. It was the estate of Jean Flagler Matthews, of the Flagler family from Palm Beach, and the buyer was Antenor Patiño, the Bolivian tin king.

I now represent Susan Gutfreund’s apartment at 834 Fifth, which is the best co-op building in all of New York. I’ve known Susan for over 40 years. The apartment is 12,000 square feet, with 100 feet facing Central Park. It’s the only older building on Fifth where the windows go low to the floor. When you’re at Jayne Wrightsman’s apartment in 820 Fifth, you have to walk to the window to see Central Park. And we just reduced the price to $75 million.

Before the internet, everybody found apartments through the New York Times real-estate section. There were no pictures in the ads back then, and you really had to pick your brain to make it descriptive and interesting. You needed something catchy. I made up the phrase “triple-mint” to describe the condition of an apartment, after the “Doublemint Twins.”

You still need a good broker to steer you into the right co-op and get you through the board. And to vet the buyer to make sure they are legitimate, or the seller will hate you. But today there is no client loyalty. Part of that is because you don’t have to have any credentials to get into a condo. With the younger crowd, you can spend months showing them condos and then they find 75 other things they like on StreetEasy and never call you again. There are plenty of new neighborhoods, too. Some people only want “new.” They only want to decorate, not renovate. They want Lutron lights and high doors. Those tall new buildings in midtown will never have the same cachet as Fifth Avenue. Unless you want to be on the 70th floor.

The other thing that’s changed is that people used to be private about money. They didn’t want everyone to know how much they paid for their home. Today they have a need to advertise how much money they have, and as my father used to say, “A spouting whale gets harpooned.”

—As told to Steven Gaines

My Curator

“Why didn’t you just call me?”

Thelma Golden saw her future.

“As a young child in St. Albans, Queens, I read magazines and newspapers, imagining everything that happened in Manhattan as I read about it. And I began to understand many of the people who occupied the city. When I was 12 or 13, I remember reading about a curator at the Metropolitan Museum named Lowery Stokes Sims. I don’t think I had a name for the job curator when I saw her picture; I just knew I loved it when I went on field trips to museums, being in rooms full of art. But I’m not sure I knew who made that possible. But seeing her picture — an African-American woman — gave me such a sense of possibility.

In my junior and senior years in high school, I was in the internship program at the Met. I still think of it as my first job. And I spent every single day hoping I would run into Lowery Stokes Sims. It never happened. When I did meet her, five or so years later, after I was a curatorial fellow at the Studio Museum, the first thing she said was, “Well, why didn’t you just call me?”

—As told to Carl Swanson

My Housemate

“I think the difference is we never felt warehoused.”

Whoopi Goldberg lived in the Chelsea-Elliot Houses, where Maria Cortes now lives.

Portfolio by Jonas Fredwall Karlsson

Whoopi Goldberg: I lived there my whole life until I moved to California after I got married. Back then, they were newer projects, or they felt newer. My room was in the back, just a bed and a bureau and windows. When I was a kid, the High Line was still being used to transport things through the city, usually at night. That’s what I looked out on. It’s a great place to grow up, because we were outside 98 percent of the time, winter and summer. We all were poor, and we all knew it, but it somehow didn’t really stop us from doing anything.

Maria Cortes: A neighbor said to me that a lady that is in a television show grew up here and that she became famous and that she took her mom from the projects and bought her a house. I believe the lady next to me knew Whoopi since she was little.

WG: Everybody’s parents looked out for everybody’s kids, so if you were in the stairway making out, your mom would know before you got finished, you know? You couldn’t do shit. And my mom was a Head Start teacher at the Hudson Guild, which was literally downstairs, so I couldn’t screw around a lot.

MC: I was 17 when I left Ecuador. I arrived by chance at this apartment in 2004. I lived through domestic violence, and the police took me out of my old apartment. To be honest, I don’t like it here.

WG: In my day, you weren’t allowed to have air-conditioning, and you couldn’t have animals. I thought how funny it would be to call my brother and say, “Dude, they got dogs now!” We had parakeets. My mother thought, If these kids tell me one more time they want an animal, I’m gonna … So she bought birds, and it was great until they heard we had birds.

I haven’t been back in almost 40 years. It was hard, because I miss my mom and brother, who are no longer with us. I wish the federal government would take better care of the projects. I think the difference is we never felt warehoused, and I think people are warehoused in these buildings. Just because you’re poor doesn’t mean you don’t want the best for your family.

—As told to Jada Yuan. Translation by Daise Bedolla.

“It’s not my style anymore. I was a little taken aback.”

Martha Stewart visits her old Upper East Side apartment, now inhabited by an ex–Real Househusband.

Martha Stewart: That was my first apartment after getting married. I was 19, a student at Barnard College, and my husband [Andrew Stewart] was at Yale Law School. We had the penthouse, on the 21st floor, for a few months. It was pretty classy for a little girl from Nutley, New Jersey! It was quite extraordinary to be so high, with a wraparound terrace; plus it was built as a luxury East Side co-op. It was owned by one of my husband’s friends’ fathers, who was a honcho at Time, Inc. I think it was $125 a month.

Tom D’Agostino Jr.: I bought the apartment in 2011 and did a full gut renovation that took about two years. Mid-century–slash–Deco décor. Raised the ceiling, changed the terrace around, expanded the footprint of the apartment to make the dining room and the kitchen bigger. Added a second bath.

MS: That apartment was very beautiful and light-filled and airy — and all white, the way it was meant to be. Now it’s much more enclosed and dark! Now it has hedges blocking the views, because the views now look into other buildings. And it’s more masculine-looking. I mean, he’s now a bachelor, isn’t he? It’s not my style anymore. I was a little taken aback.

TD: Martha baked me a beautiful apple pie with apples she had picked on her own farm, so we had coffee and pie together and spent an afternoon talking. She said the apartment was totally different and remarked what a wonderful renovation.

MS: I knew Tom was on The Real Housewives [of New York City]. That’s not my cup of tea, but I know some of the housewives. I think he liked the fact that I brought him an apple pie. He still hasn’t returned my dish, though.

New York: Martha, that’s my fault.

MS: If you could remind someone to give me back my dish, it would be nice. It’s my favorite apple-pie dish.

—J.Y.

“I think I maybe got a teeny bit of pot in that park once, out of about nine tries.”

Matthew Broderick lived in this Washington Square apartment, where John Wesley lives now.

Matthew Broderick: We moved there from a few blocks away on Fifth Avenue when I was 4. I lived there until I got my first apartment on my own, in my early 20s. The living room faced the park, so it was all trees and no high buildings. So I watched the Twin Towers go up out of the living-room window. Washington Square Park was a very different place. You used to hear bongos basically all day through the windows in that house. You could not walk through the park once you were a teenager without being offered pot … which was actually, I found, not pot very often. Oregano or mattress filling, like sort of foam. I think I maybe got a teeny bit of pot in that park once, out of about nine tries.

My parents got robbed in the apartment once. A man broke in with a knife and made them get their valuables. There were two fires while I was there. One was my friend’s apartment who lived next door to us. The other was on the third floor, below us, where Uta Hagen lived. And I remember that, because my father refused to leave the apartment. He didn’t feel it was going to spread, so he decided to stay. I think there was a ball game on.

After my dad died, my mom lived in that apartment with the artist John Wesley. I hadn’t seen Jack in about ten years, and he was much older than I thought. I’m glad I saw him. He was her beau for the last several years of her life, and then she died and he stayed, which was a very nice thing for the building to let him do, because the rent would be insane now. When my mom died [in 2003], the rent was still around $800 or $900 because of rent control, and it was four bedrooms with a big living room and an eat-in kitchen.

The kitchen is pretty much exactly the same. I remember every screaming fight. I remember Thanksgivings in that kitchen. I had every first there. I had my first girlfriend there, my first play I was paid for. It’s weird that eventually some other family will live in it and that will be that. The house I live in with my family now, it’s from 1870, and I’m like, I wonder what happened in here?

—J.Y.

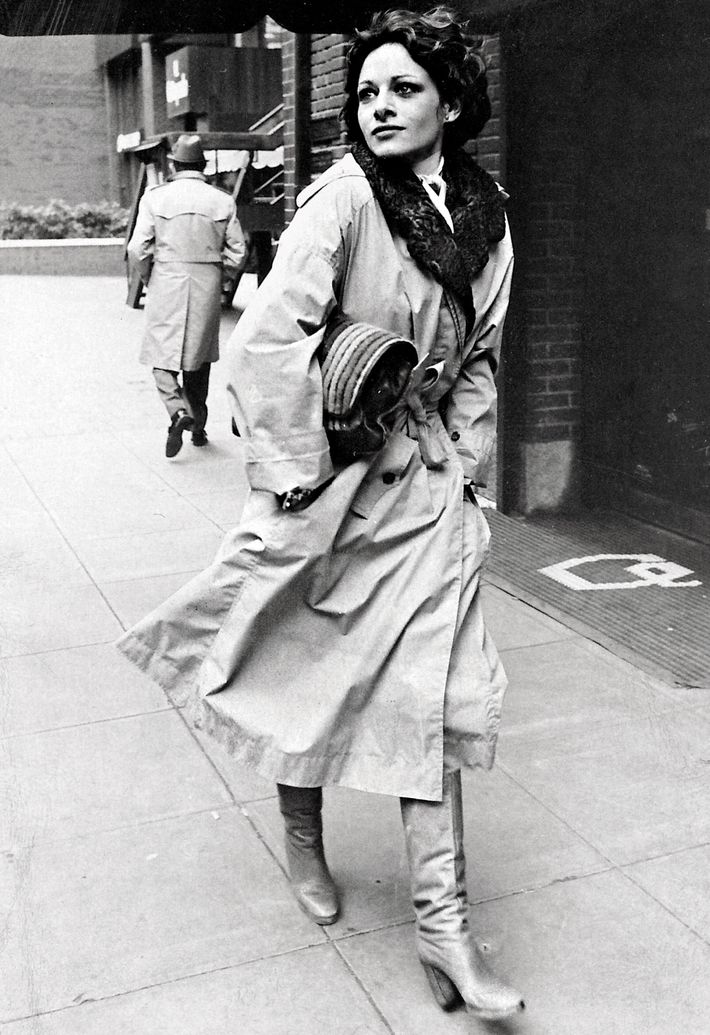

“I would buy six or seven Morton’s chicken pot pies that were 27 cents a pot pie.”

Lauren Hutton meets Lauren Taylor in her old Greenwich Village apartment building.

Lauren Hutton: I was 21, 22, and new to New York, and I wanted to be in the Village so I could see a sky, because I’m a country girl from the South and I couldn’t breathe above 14th Street. So I saw an ad and came down. The first apartment I had was in this building with five girls in a three-room apartment and none spoke to me. I had a small daybed under the window in the living room. I got a table and two chairs because I heard from some new people I’d met that you could go to Park Avenue and pick up furniture from the street. Different chairs from different garbage piles up on Park. Then I got this studio apartment upstairs from my old apartment, with a Murphy bed. I made $50 a week, and I was paying $75.

Lauren Taylor: I wish it was still that price! I grew up in Houston, moved to New York six years ago; I work for Bumble the dating app. This my fourth apartment in the city. It’s a millennial thing. We move around jobs, we move around apartments.

LH: Across the street was a jail.

LT: It was the only women’s jail, I think, in New York.

LH: A woman’s house of detention, they called it. It was mostly people who couldn’t protect themselves and didn’t have lawyers. Their pimps would come by on Saturdays and Sundays. There was a tremendous amount of action. A couple fights you’d see on the sidewalk, but it was amazing.

Another thing that happened around here was there were some brave boys who would wear pink rollers in their long hair. They were called drag queens in those days. But I think it was just brave guys who liked other guys. They were the biggest traffic on Christopher Street, and I would sit in that window a lot and look out and they’d wave up and I’d yell down. It was nice.

Oh, and I lived on pot pies. At the beginning of the week, I would buy six or seven Morton’s chicken pot pies that were 27 cents a pot pie. I could cook. I mean, I knew how to take it out of the freezer and put it in the oven and, boy, I was happy.

LT: Were you modeling then?

LH: I was working at Christian Dior as a house model. They had a modeling room on, I think, 36th and Seventh Avenue, and it was just me and another model who was much older than me. She was almost 30, which is weird. Who knew a 30-year-old woman? And she was always trying to get me to go out with her and her executive boyfriend, who I think was married.

LT: Did you have a first boyfriend here?

LH: The first love of my life, and he had, it turns out, a lot of people who thought he was the love of their life.

—J.Y.

My Boss

“She made those nice New York intellectuals seem like the Sopranos.”

Taking dictation from Diana Trilling.

By Cathy Horyn

Where do our thoughts go when we are growing up and suppose that we have no further use for them?” Diana Trilling asked at the end of an essay about her experiences at summer camp in the late 1910s and ’20s. “The Girls of Camp Lenore” ran in The New Yorker in 1996, two months before her death. I would be among the mourners at her funeral, 20 years now separating me from the time I worked for her as a secretary, really a girl Friday. I find that I say that line to myself a lot, half in wonder at the mysteries of memory and half in love with the sound of the words — especially whenever my mind reels back to the summer of 1977, when, in addition to Diana, I worked for a woman named Mary Loeb. Mary, 76, had recently gone blind and hired me to read to her on weekends at her apartment on Sutton Place. We began with Lolita.

The two women were as different as two people could possibly be who happened to be born in the same era in the same city. One was an intellectual powerhouse, the widow of Lionel Trilling. Diana was about to have a spectacular second act — on her own — with the publication of Mrs. Harris, her 1981 account of the Scarsdale Diet Doctor murder, followed by a memoir of her marriage. Mary had never needed to work, but through her late husband’s family she became loosely connected to the world of artists and writers. His cousin was Peggy Guggenheim, and his brother, Harold, had founded the literary magazine Broom. I remember her delight at telling me about the time she met F. Scott Fitzgerald at a nightclub in the 1920s. We were sitting up late in her room, her wig removed for the day, a Marlboro burning in an ashtray on her lap, when she recalled being out with her husband and Maxwell Perkins, the editor, and a tipsy Fitzgerald approaching their table, his eyes glued on Mary.

“What did he say?” I asked.

She let out a throaty laugh. “He said, ‘Tell me, Max, who is this beautiful Jewess you are with?’ ”

I can see in hindsight that it was strange for a college junior to be spending so much time with two old ladies, especially when you consider that the city was in the throes of punk that summer. But punk barely entered my consciousness. My father, an advertising executive from Ohio, had sent me off to Barnard with the understanding that he would pay tuition if I covered my expenses, including rent ($130 for my share of a two-bedroom on West 114th Street). I knew no one in the city, and as a transfer student from a small college in Ohio, I’d found it difficult to strike up friendships with girls who’d bonded as freshmen. Yet I was not lonely. On the contrary, I felt intensely at home on the Upper West Side, with its anomalous mix of students and old people whose faces told you they had survived the Holocaust. I loved wandering into the gloom of the West End bar and thinking, Kerouac was here.

The Trilling apartment was on the ground floor of 35 Claremont Avenue, and when I went to be interviewed — or, as she put it, “to see how we will get along” — she greeted me with a smile I would come to know: at once warm and weary. Dressed in dark wool, the sleeves of her outfit pushed to the elbows, she showed me into a large, dim living room, and I took a seat in a wing chair. Then 71, she was totally self-assured, easily the most formidable human I’d ever met. And at that moment I was glad Lionel was dead, because I don’t think I could have faced them both.

Diana had developed tendinitis and wanted to avoid the strain of letter-writing by dictating them. The volume was enormous. The year before, she’d found her picture on the front of the Times, next to her friend Lillian Hellman. It was the literary catfight of the season, though actually the fight was between Diana and Little, Brown, which had canceled publication of her new book of essays when she refused to delete comments critical of Hellman’s Scoundrel Time, also a Little, Brown book. There was still fallout from that episode — Diana had moved the book, We Must March My Darlings, to Harcourt — plus the usual correspondence to friends.

Well, not usual. It was a quiver of names at the heart of American and British cultural criticism. Isaiah Berlin, Jacques Barzun, Norman Mailer, Paul Fussell. Two or three evenings a week, I would sit in the wing chair, scratch down what she dictated, and pray I didn’t miss anything. Then I would walk the two or three blocks to my apartment, past the Chock Full o’ Nuts, and in my room type “Dear Norman” and “Isaiah dear” on her letterhead. The next day, I would take the pages back to her to be proofread and signed. I saved no letters, of course, but they were always remarkably like Diana: unsparing, precisely worded, surprisingly affectionate.

Diana had planned to be an opera singer, until a thyroid condition nixed that. So when she began to write, she told me, her musical training helped. It was important to write not just with your head and heart but also with your ears. Listen to the sound of the words. Another one of her lessons was harder for me to put into practice. It was: Be contentious. Stand your ground. Until I sat in that living room of hers, I’d never imagined that so many people could be mad at one another. She made those nice New York intellectuals seem like the Sopranos. And she was the fiercest of all. No one was let off her moral hook. I once told her that, coming from a small town, I didn’t understand how a person could be so critical and expect to get along. She looked at me like I was a Martian.

I continued to work for Diana until I graduated, in 1978. That summer I moved to Chicago, to begin graduate school in journalism, and in September I received the first of many letters from Diana, typed by a successor.

Cathy dear:

As the summer progressed I fell ever deeper into a slough of despond, to the point where to have answered your letter would have been a long-distanced cruelty. What a yowl I’d have emitted! It was a horrid summer, I hated every minute of it, never stopped scratching and still feel as if my body were encased in a half inch of heavily peppered molasses. This is not intended to be funny, it is for medical use for any doctor with whom you may happen to take up in your adventurous life in Chicago. But if my health hasn’t been improved by my return to the city, surely my spirits have. By the way, my menage à cinq quickly became à trois and ended à me alone. I think I need some references from old employees.

Your j-school (see how quickly I learn) experience sounds absolutely perfect, including the fellow from Fordham. Imagine anyone of his/your age knowing all these things. You must ask him if he would wish to be adopted and I don’t mean by Hellperson. Has term started again? If it has you mustn’t bother to answer this letter, just get right back into your thousand professional words a day. There could not be better training.

I do miss you, think of you often, and send you my best love.

My Cellmate

“Should I call my mom?”

When the elevator stalled, it was just me and him.

The doors close and then the floor drops from beneath us and then it’s back under our feet. He looks at me and I look at him and I say, “Oh my God,” and the floor jolts away and back again and he grabs my arm. I look at the control panel and can’t figure which possibility is the right one — firefighter helmet? Oh. That’s not a button, it’s a light or else just some plastic thingamajig. My companion is saying something quickly. I think it’s a prayer.

“Should I press this one?” I ask the man.

His shoulders raise a little and his head rattles on his neck. He’s telling me he doesn’t know. I press the one that says EMERGENCY CALL and a loud alarm goes off.

“Hello! Are you okay?” There’s a little tinny voice yelling through the grid of holes above the buttons. The man in the elevator nods at me, and I understand that I have become chief, in command in our new, three-foot-square country.

“Yes!” I yell back (the alarm is still screaming).

“Help is on the way!” he yells back.

The man looks me in the eye and says, “Should I call my mom?” This was unexpected. I can see, though, that he wants and needs to call her, and so I say “yes” enthusiastically. After he hangs up, he tells me that his mom is going to try to call the building. I wonder what in the world this woman could possibly achieve, but I feel strangely optimistic, too — if you raised a child who thinks of you the moment an elevator stops, you must have done a few things right, right?

While he’s texting someone who cares about him, I’m telling Twitter and Instagram where I am. I suggest a selfie together, which he agrees to, throwing his arms across his chest and making two V signs before immediately dropping them and pulling a face when I turn the camera away. “I don’t like pictures,” he says. He’s so shy, I think of a rabbit or some other thing that you want to pick up and hug despite knowing it would be cruel because they’d rather be left alone, unhugged. I guess I’m cruel. There are ten selfies in my phone by the end of the night.

A co-worker sees my tweet and asks if I’m okay in there. I say I’m worried about my worried comrade. She replies with screenshots from an anti-anxiety exercise, which I suggest we complete together.

“Okay,” I say. “Name four things you can see.”

“Okay, I see you, the mirror, that wall, and that light — is that four?”

“Yep, what’s next? Okay, name three things you can smell” (I suddenly become very self-aware).

“Are you okay in there?” It’s the voice behind the wall colander again.

“Yes!” I say.

“Who’s in there? What are your names and what floors do you work on?”

I gesture for the man to step up and take his turn on the microphone.

“My name is Matthew Washington and I’m a student at CUNY,” he replies in a voice I suspect is too quiet for the operator to hear over the alarm, but he does. He replies, “And what about the woman?”

“She’s Helen Washington.”

Blushing, I whisper as loudly as I can, “I think he means me, not your mom.”

—Mona Chalabi

My Characters

“She has nothing to give him but her eyes.”

Playwright Mfoniso Udofia on five strangers she saw on the street whom she wants to see onstage.

1. It’s after the school day, and she pauses by the homeless man, on Eighth and 44th, who holds a sign asking something like: “Am I invisible?” She stares at him.

She has nothing to give him but her eyes.

2. He is the Mandé Uber driver from Côte d’Ivoire whose perfect English is accented with a French r and whose linguistic musicality reminds me, somewhat, of my own West African home. I ask him how many languages he knows. He lists: Jula/Dyula, French, English, and pidgin English. I got the sense that his list was not long enough.

3. She wears an Iron Maiden tank top and multicolored Lycra workout pants. One can almost make out the individual bundles of muscle that link her together. Her smile is as built as her body.

4. He is the man conversing with the Open Air. He walks the length of the B train slowly, finding an empty seat all the way at the end. His conversation with the Open Air becomes colorful. An argument breaks out. Then, the Open Air and the Old Man reconcile and laugh, talking until the doors to the train open.

5. We walk to the shop together, catching up. We enter, I sit down, and she begins the five-hour process of braiding my hair. She offers me boiled peanuts as she works. I inquire about her daughter and ask if she is able to visit her family in Togo this year. Some hours later, she takes a break. She kicks off her shoes, washes her feet, lays out her mat, faces east, and prays.

My Sammy

“He didn’t believe I had caused Hillary Clinton to lose the presidency.”

Visiting an old friend has its upsides.

By Lena Dunham

When I was in seventh grade, we moved to Brooklyn and got a dog, two signs of domestication my father had sworn he’d never partake of. Despite having sired two young, clumsy daughters, he was convinced we could remain forever in an industrial building with condemned stairs and no certificate of occupancy, and that the pressure to wash your jeans was a conspiracy by Big Downy. But there we were, on our Sesame Street–perfect block of carriage houses with a terrier who rode in the back of a gray Volvo. “This is fucking humiliating,” my father muttered as he loaded us in for a drive to brunch. Rage, rage against the changing of the boroughs.

But I took to our new neighborhood like Liza Minnelli to a broke gay man — it was as if I’d been waiting my whole life for the chipper sitcom that is Brooklyn Heights.

“Good morning, Mr. Construction Worker Leering at my non-breasts! Pleasure to see you, Old Lady With Substantial Day-Drinking Problem!” I worked part-time at the video store. I had friends at the diner, the dog park, and Talbots, where I’d stop to peruse discount lady’s separates. And I tacked my business cards up in Pet’s Emporium. “EXPERIENCED PET GROOMER,” they said, though experience simply meant a pair of clippers purchased at sale prices and a relentless will not to be bitten. I was too scared to actually use the razor, so I gently trimmed dog bangs. I was never hired twice.

But to build a business, you need a champion, and mine was Sammy, an affable Palestinian man who spent most of the day outside his shop, the aforementioned Pet’s Emporium, greeting the neighbors, giving dating tips to unmarried female customers, and ordering around the sons (four out of his eight) who worked for him in what was actually a stunning parlor floor apartment, though it was far too stuffed with bird seed and hamster wheels for the classic architectural details to matter.

I was quickly fired from the video store (turns out the customer is really, actually, and totally always right, even if it’s about gang-bang porn). I was 70 percent friendless and the market for an untrained 15-year-old dog groomer is niche, so I had a good amount of time on my hands and that time was spent with Sammy.

Sometimes he let me stack and organize product in exchange for a small store credit. Other times I passed out flyers on special deals. Often we just read quietly, what my mom would call parallel play. “My beautiful Lena!” he would cry when I appeared in the doorway, in the least-sleazy singsong a 55-year-old man can direct at a 15-year-old girl.

I really don’t know what my parents thought was going on. “Where’s Lena?” “Oh, she’s spending Saturday at the pet store with her best friend and mentor Sammy, stacking litter boxes in exchange for organic rabbit pellets!” Sammy let me bring my actual rabbit, first name Chester, last name Hadley, who would sit behind the register in a cardboard box chewing on Timothy Hay. Once, Sammy sent me to cut the nails of an elderly blind woman’s cat, and she paid me with a brooch I still have, a fake ruby in a gold-plated filigreed heart. Sammy marveled at it. “What a treasure!”

When it was time to go to college, Sammy and I had an emotional farewell. I promised to be studious, responsible, and kind — and I promised to visit. But I never visited. My parents moved. My obsession with small-animal husbandry faded. I instead became obsessed with what I ate, what I wore, and whom I fucked (or more accurately, who was refusing to fuck me). Eight years later, I moved back to the neighborhood, but I avoided Sammy’s block. Despite certain successes, it was hard to imagine that I had fulfilled Sammy’s order to “be good.” I had HPV, there were whole neighborhoods I was scared to walk through for fear of a yelling match with a tattooed landscaper, and sometimes I went to the bodega at 4 a.m. and ate six to seven packaged croissants then threw them up. I had no pets.

But one day, having turned 31 and celebrated my five-year anniversary with someone I considered to be the embodiment of good, my feet walked me where my mind had refused to go. It was a Sunday. Would the store even be open? Did Sammy still run Pet’s Emporium or would one of his sons stare at me blankly, wondering who this woman with unbrushed hair and daytime pajamas asking for his dad was?

“I don’t know what’s going to happen,” I told my boyfriend as the door creaked open. But there behind the counter was Sammy, in his old spot nestled between the leashes and the dog-breath neutralizers. “My beautiful Lena!” he said without a beat. I grinned. It quickly became apparent that he had no idea what I’d been up to for a dozen years — he hadn’t read about me in “Page Six.” He didn’t believe I had caused Hillary Clinton to lose the presidency. He had not seen my nipples and bush on TV. He was simply happy I’d kept up with this whole being-alive thing. I told him which of our family pets were still living and which one had died after taking a huge shit on my mom’s color printer. I told him I was “a writer, for real now.” I presented my boyfriend like a trophy.

“Look at you!” said Sammy, who had kept a strong business rocking through the financial crisis, the Starbucks-ification of Montague Street, and the challenges of being a human on this earth. No. Look at us.

My Board

“He told me, ‘They really should have attack dogs in the park.’ ”

Three times a year, the members of the Central Park Conservancy Women’s Committee meet at Doubles.

Anne Harrison, former president of the board: I got involved sitting next to Norma Dana’s husband at a dinner, and he told me, “They should really have attack dogs in the park,” and I said, “You know, I don’t think that’s such a great idea, but I love the park!” So he grabbed my hand and said, “I need to introduce you to Norma,” who is one of our founders.

Gillian Miniter, former president: My husband will call me and say, “I just had a business meeting, and this guy said his wife wants to get involved with the park; would you please call her?” Sometimes we end up with board members that way.

Alexia Leuschen, future president: My high-school gym class played softball in the park, but it was littered with needles.

Suzie Aijala, current president: I was mugged there when I was 9. It was disgusting.

AH: I remember my daughter picking up a cigarette butt and thinking, Really? This is what it’s come to?

GM: We have one of the largest fund-raisers in the city — the hat luncheon. What did we raise last year, $4 million?

SA: Four and a half million.

GM: And the trips! We went to Cartagena in January, and we’re going to Charleston.

SA: We’re workers. We’re not fluffy. You know what I mean?

AL: A lot of people come here and think they don’t know anyone and then they realize that it’s just one, two, three degrees of separation.

GM: We’ve got West Siders, we’ve got downtowners.

AL: We try to get them when they have babies!

—As told to Amy Larocca

My Blind Neighbor

“He asked me to help him make his computer talk to him again.”

Abandoned in the Bronx.

By Brandon Harris

I heard Sean before I ever saw him. Screeching electronic beats would fly through the air near midnight into my previously quiet $800-a-month studio in the back of an unattractive two-story building on Bathgate Avenue in the Bronx. When it started, I had lived there only a month, in exile from a Brooklyn that seemed to hold only dead-end living situations and closer to my job as a visiting professor at a university I owed tens of thousands of dollars to. The sound was soon followed by the smell, the saccharine stink of menthol cigarettes creeping into my flat from our shared hallway, where my neighbor stood to smoke. Sean often left his door open at night, and so I followed the rhythm of his day, the sounds of movies giving way to white noise, before the late-night bursts of music production would rattle me awake.

I can’t remember how I first recognized that Sean was blind. Perhaps it was when his aide, a stricken-looking younger African man with red-rimmed eyes and a weary way, would walk him back into the building or deliver food. Perhaps it was when I came out to ask him to not smoke in the hallway, which, come to think of it, I never did. I do remember the way we slowly got to know each other, two midwestern Negroes at the end of a city, and the way he came to rely on me to find things he had misplaced in his apartment, or asked me to help him make his computer, which he used more than most people who could see, talk to him again. He said he had spent most of his adult life blind, his vision taken in a gangland fight over some silly beef that his every moaning call to his aide suggested he would never cease to rue.

He was sad when I moved out. I didn’t tell him I was moving into a massive, rent-controlled loft in Dumbo, one of the last of its kind, given the neighborhood’s transformation, one that an ex-lover and ex-colleague and soon-rival were illegally subletting to me. Or that I was from Cincinnati; I’m pretty sure that, instead, I claimed to be from Detroit. I donated a desk and some marijuana to his cause. I claimed I’d come to visit on my way to get some fresh mozzarella and some prosecco (on tap!) at Mike’s Deli, on the avenue, but then I never did.

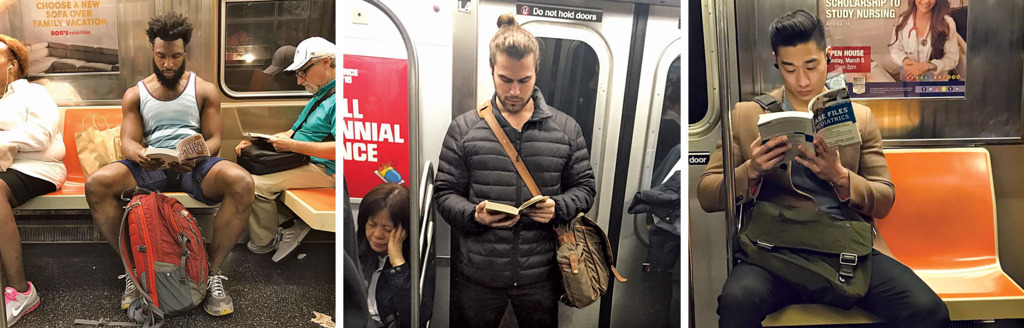

My Fan Club

“Am I reading on the train now to maintain my status as a hot dude reading?”

Instagram famous on the F train.

Benjamin Roberts: I had just left the gym; I had a little pump going. In the caption on the photo posted on Hot Dudes Reading, the account owners guessed that I was a CrossFitter, so they nailed that one. The photo was 100 percent candid, though I did have this weird sense that I was being watched. That day, I was reading Dream of the Red Chamber, by Cao Xueqin, which is a classic Chinese novel. I had only started it a couple of days before, so that’s why it looks like I’m about 20 pages into it.

My girlfriend at the time was the one to break the news that I was officially a Hot Dude. She said that a couple people from work told her about it. Afterward, I started to go through the mental gymnastics of, like, Am I reading on the train now to maintain my status as a hot dude reading?

The best thing about it all was attending a fan meet-up after the Hot Dudes Reading book came out in 2016. A British girl who was there introduced me to the writer Siri Hustvedt and her novel What I Loved. I don’t even really think of myself as a “hot dude,” but it’s nice to be an ambassador for the brand. I still wear my hair in a man-bun sometimes.

—As told to Allie Jones

My Gang

“Boy, you want to run for the Assembly?”

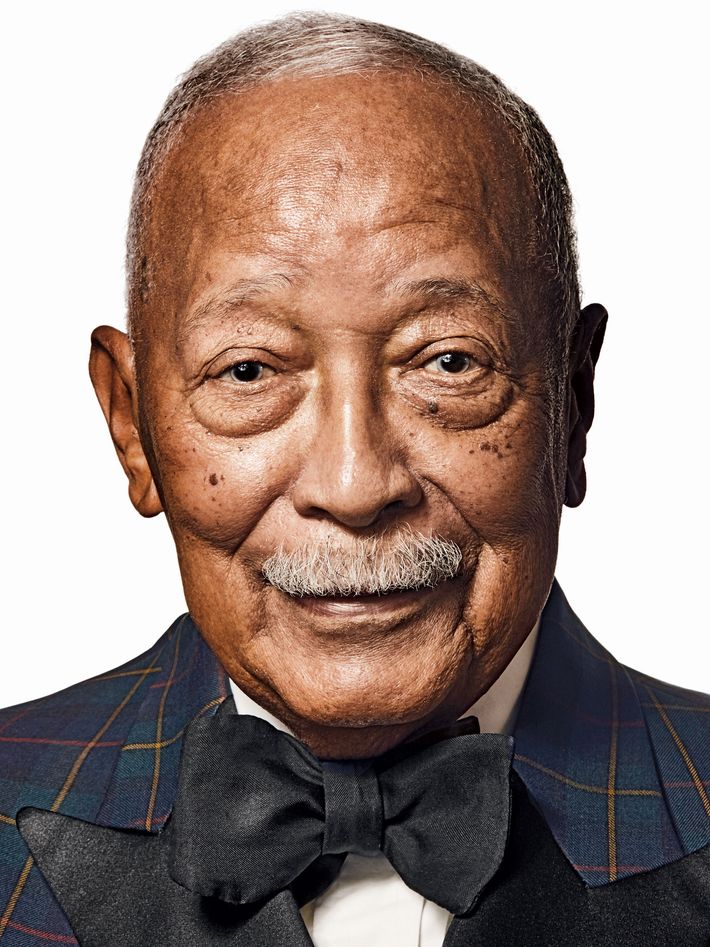

David Dinkins remembers all his opponents.

“Way back, like 1939, my father-in-law, Daniel L. Burrows, had been in the State Assembly. He knew all the people, politically, and he wanted to see that his son-in-law got a break. And it was he who first introduced me to Ray Jones.

Ray’s nickname was “the Fox,” and that was appropriate, because he was tough, very smart, and smooth. He was our local district leader, and he became the first black leader of Tammany Hall. The political clubs, that was the method of networking in that day. A lot of lawyers were members, and they’d come once or twice a week and help people with their legal problems for free. Ray would also help people get jobs. One of his favorite sayings was “Nobody does anything for nothing.” So the community could be counted on to vote consistently Democratic.

One night, Ray came out of his office with a big cigar and said, “Boy, you want to run for the Assembly?” I said, “I don’t know — I guess.” There had been a federal lawsuit, and the result had been an expansion of the number of seats, creating a space for which I could run. So I won. Now I’m hopelessly hooked on public service. This is what I want to do.

Percy Sutton, Charlie Rangel, Basil Paterson, and I — the so-called Gang of Four — we always believed nobody gets anywhere alone. Everybody stands on somebody’s shoulders. It was Ray on whose shoulders I stood.

There were many positive aspects for city government of the clubs’ being in control, such as balanced tickets: Time was, you could count on a citywide ticket in the primary having at least one Jew, one Italian, and so forth. There were certainly some downsides to Tammany Hall too.

There came a time, in 1977, when Ed Koch and Mario Cuomo were in the runoff for mayor. There was always tension between blacks in Harlem and those in Brooklyn. The word came that the black political bloc in Brooklyn was going to support Cuomo. So Percy, our leader, said, “Fuck ’em. We’ll support Ed Koch.” Because they both looked alike to us anyway. Here’s the thing: Ed Koch had been a very progressive, liberal member of the City Council and the Congress, so it sort of made sense to back him. Ed was honest. He was arrogant. But he understood one thing: As he used to say, “If a sparrow falls in Central Park and you’re the mayor, it’s your fault.”

Over the years, he moved more and more to the right. So much so that it was determined somebody should run against him in the 1989 primary. I never started out saying, “I want to be mayor.” But it ultimately fell to me. I never want it to sound like I’m saying I was drafted, but in a way I was. By Basil and Jesse Jackson and Charlie Rangel. And Bill Lynch — oh, what a sweetheart. Jesse used to say, “You don’t have to be loud to be strong.” I found that valuable. I remember Harry Belafonte saying, “Dave, you must run for mayor.” So I ran. We got 51 percent. I can always say I defeated Ed Koch and Rudy Giuliani in the same year.

Well, it was a very difficult time. The way the press wrote of the high crime rate in the ’90s, it was as though there was no crime on December 31, 1989 — just the next day, when I took office.

The biggest disappointment? Crown Heights. The real tragedy was the deaths of Yankel Rosenbaum and Gavin Cato. There wasn’t a hell of a lot we could have done differently. The sad thing for me personally, I was accused of holding back the cops, letting blacks attack Jews. This was not true. It was painful, painful. The other thing that sticks in the minds of many people is the Red Apple boycott. I wish now I had crossed the picket line sooner.

Rudy is not a nice guy. He really isn’t. Simply put.

History is kinder and more accurate in many cases than the contemporary observers of the scene. I’ll read about things we did in City Hall — in housing the homeless, in Safe Streets, which turned things around on crime — where we get some credit now. Eli Attie, a great little writer, he later worked for The West Wing; he wrote the concession speech in 1993, except for the last sentence or two. Those were by Peter Johnson Jr., a lawyer and one of my aides. Peter wrote, “Mayors come and mayors go. The city must endure.” See, that’s the whole point: No one gets anywhere alone. All right, young fella.

—As told to Chris Smith

My Game

“Lin’s the worst player of the group. He thinks three pair is good.”

Once a month, some Broadway producers and their friends play poker in a midtown office building.

Steve Gutman, former president of the New York Jets: Seven or eight years ago, Manny Azenberg and I were on the way home from Il Riccio, and Manny said, “We ought to get a poker game. You know anybody?” I said, “Well, Ned I’m sure would play,” and Manny said, “That’s enough from you. I’ll add the rest.”

Ned Gurevich, insurance executive: We lived in the same neighborhood in the Bronx in the 1940s. Manny and the two Steves all went to Bronx Science.

Manny Azenberg, producer: We called up about 12 or 14 men, including Lin [Manuel Miranda], who isn’t here tonight.

MA: Lin’s the worst player of the group. He thinks three pair is good. But Jeffrey plays, so Lin and Tommy Kail found out.

Jeffrey Seller, producer: Tommy could play a little poker. Lin couldn’t play for shit.

MA: Everybody at the table can afford much more. But most everybody here grew up without. So they deal with the money as if it’s real. If you raise me $2, it’s “You fuck!”

JS: The day I had to announce that we were closing The Last Ship, the failed musical that Sting wrote — I was going to lose definitely over a million dollars personally, but that night I won $200 here. It was a small victory amidst a colossal defeat.

MA: Steve Gutman’s the best player.

SG: That’s absolutely not true. The trick is just not to lose too much when the cards aren’t going your way. I’ve never played at any other tables.

Steve Karmen, composer: Don’t believe Steve. It’s like the girl who says “I never did this before.”

Bob Fried, accountant: Jeffrey does extremely well because he doesn’t give a shit.

Ron Shechtman, attorney: I got business with Jeffrey, when I represented the cast in Hamilton.

BF: But Manny will not allow shop to be talked.

Jerry Patch, artistic director: There’s a common language between us, but we’re not allowed to speak it.

JS: No show business.

—As told to Boris Kachka

My Family

“Every time I talk to my sister, she’s crying.”

Waiting at JFK for the flight from San Juan.

“I talked to my mother before Hurricane Irma, and she was like, ‘Oh, you know us islanders — we’ll be fine.’ Then before Hurricane Maria, she was like, ‘I’m scared. This is gonna be bad.’ That was the last time I talked to her. I had a plane ticket for a while, but I couldn’t get ahold of her to tell her. She has two sisters, but they’re an hour away. One of my aunts called my cousin, who found my mom on Saturday and told her, ‘You’re leaving Monday.’

“She’s 62. She lost everything. She’s coming here permanently. She just put a few things in a backpack and that was it.” —Marie Singh, Hartford

“We’re waiting for my two nieces. They live in the mountains, and nobody wants to deliver water or food there. Every time I talk to my sister, she’s crying. She goes to the store, and there’s a four-hour wait, and then inside, there’s only one loaf of bread. Plus, there’s no jobs right now, so there’s no money. She’s worried that if she leaves, she won’t be able to get her job back.” —Lourdes Calderón, Hell’s Kitchen

“We’re still waiting for my father and grandfather. The power is out. People are fighting for food — they’re even fighting for ice.” —Michelle Rivera, San Juan

“My daughter stayed. She’s young, so she can handle it. But I got sick — maybe from the water? The stress? Who knows.” —Carmen Lopez, San Juan

—As told to Reeves Wiedeman

My Motivator

“Good money! Good money! Good money!” Lessons over sit-ups.

By Hari Kunzru

For some time, I wasn’t sure if Jimmy Love was his actual name because he talked quickly and mumbled. It turned out that the “Love” was an “I’m a lover not a fighter” personal statement and his surname was something else entirely. As a new immigrant to New York, I wanted to fit in. I knew that the culturally appropriate thing would be to hire a shrink and a trainer, but I couldn’t afford both. So I walked through the doors of an East Village gym and signed up for a trial session. Soon, I was doing push-ups as Jimmy held his cell phone in front of my face, the screen displaying a motivational image of a BMW convertible, chanting ecstatically, “Good money! Good money! Good money!”

The car was motivating for Jimmy Love, since he wanted to buy it, and it was nice that he thought I’d be as excited as he was. I grew fond of his energy, his constant amazement at the world. He’d launch into anecdotes that assumed prior knowledge of the complicated politics of the gym, or his favorite musicals, or the names of other clients. He once asked me if mermaids were real, and, when he saw the expression on my face, claimed he was “just checking.”

Jimmy Love was an extreme neat freak whose romantic life was ruled by various paranoid maxims. You never want to let them know where you work. Never let them leave a toothbrush at your place. He would ask my advice, mostly about geography.

“She’s from one of those A countries.”