On an average game night, only 200 people watch basketball in Hunter College’s gym. But last Saturday night, 1,200 people have filled the place. To watch a roller derby. They have all come to see the Bronx Gridlock, undefeated since 2008, face the Queens of Pain in a marquee Gotham Girls Roller Derby bout. It’s yet another sellout for the league, which has been around since 2003. If Bronx were to win, they would coast to the championship game as the top seed. If Queens were to somehow take down the favorite, the two teams would share first place and likely meet again in the championship game.

An hour before the match starts, the gym is already brimming. Families, couples, and friends sit on wooden benches, and most don’t have any idea what they’re about to see. There are more women than at a usual New York sporting event. Vic Gillespie is one of them. For $35, she has a VIP seat down on the floor, despite never having seen a moment of derby. Her friend Riayn Fergins, a derby acolyte who went to her first bout May 22 and hasn’t missed one since, dragged her here. “She said, ‘I’m getting tickets and you’re coming,’” Gillespie says.

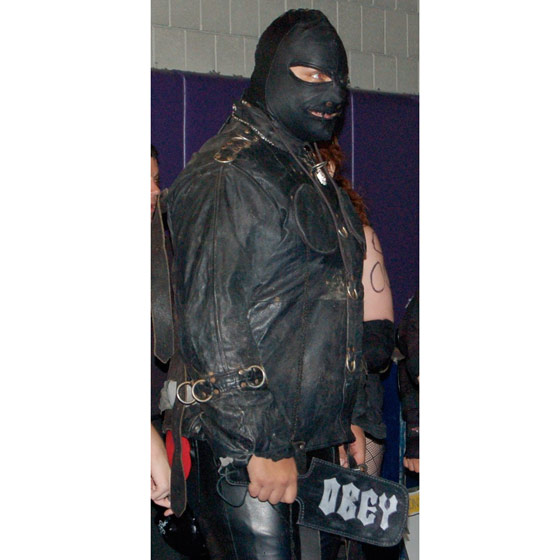

When the players are finally introduced, the crowd realizes this is not just about women hitting each other. It’s about women hitting each other with flair. The Queens of Pain roll out first, fronted by their mascot, the Persuader. He, like the rest of the Queens, is dressed in sadomasochistic garb. His ski mask is on as tight as his chaps, and he carries a paddle that reads, “OBEY.”

He is led around the track by Greta Turbo, who pulls him by a leash. As the other Queens emerge on the track, they smack the Persuader’s ass, aiming for the red underwear showing through the chaps. He wobbles on his skates every time they make contact.

The players have all found a way to add some personal expression on top of their spandex. One Queens skater, Hyper Lynx, is wearing small cat ears on top of her helmet. Puss n’ Glutes, a nurse by day, Queens rookie by night, is sporting Technicolor underwear as outerwear. Stevie Kicks, in homage to her namesake, has “EDGE OF” stenciled next to her number, 17, on the back of her jersey.

Everyone has a nickname. Donna Matrix, Haulin Cass, Pippi Strongstocking, Ani Dispanco, Beyonslay, Dainty Inferno — the innuendo seesaws between sexual and violent. Even the non-players get into the act. The medic is called “Ace Bondage.” One of the referees has “Ref in Peace” written across his back.

As the skaters line up for the opening whistle, the crowd stomps on the floorboards and screams until they can’t hear the echo. The announcers — who aren’t nearly as hyperbolic as they should be — urge them to count down. “5,” they yell. “4, 3, 2, 1!”

The first whistle blows. Four skaters from each team start running on their skates while linking hands and jostling for position in the pack. A few seconds later, the whistle sounds again, releasing two new skaters, the teams’ fastest. These trailing skaters are called “jammers,” and they’re the ones that actually score the points. Every time a jammer laps an opposing player, she adds to her team’s tally. In her way are the four blockers from the opposing team, whose only purpose is to slam their bodies into the jammer to prevent her from getting by. Everybody will keep skating until two minutes go by or the leading jammer decides to end the round, known as a “jam.”

The teams bring out their best players for the first jam. The jammers: Bonnie Thunders of the Bronx vs. Suzy Hotrod of Queens. They’re both lithe, skating low to the ground to slip through the pack. Before the match, Hotrod, who has a smile as wide as Julia Roberts’s and tattoos as plentiful as Dennis Rodman’s, told me she wasn’t just the team’s captain, she was its “spirit guide.”

As the jam gets under way, Hotrod breaks through the pack first, and the crowd clamors. The spectators don’t know much about how the sport works — they’re especially confused when penalties are called — but they know a jammer on the loose is something to celebrate. Hotrod whips around the track, going somewhere north of ten miles per hour and looking like a speed skater. As she approaches the pack to try to pick up some points, Thunders is right behind her. The Bronx players converge on Hotrod, trying to block her progress. She squeezes through a few, but then wobbles and starts to careen toward the VIP benches on the side of the track. As she crashes into the spectators, she ends the jam, picks up three points, and reminds the people trackside that they, too, are a part of the bout.

Fifty-nine minutes of play, two injuries, countless penalties, and a half-dozen lead changes later, Queens is on the cusp of victory. With just a few seconds left, there’s one last jam, and Queens jammer Hyper Lynx ices the match for the team, as the gym shrieks again. Queens has done it; they have handed Bronx their first lost since 2008. Queens’s coach, Buster Cheatin, is beside himself, his hands apparently glued to the top of his head. Their cheerleaders swing plush sex toys around. Lynx whips off her helmet to reveal a shock of purple hair and skates over to kiss somebody wearing a silver crown. Her cheeks are moist with tears or sweat. It’s hard to tell which.

Hotrod, who tallied 69 of Queens’s 128 points, is rightfully exultant. Still wearing her helmet, she can’t stop smiling. Or at least I think she can’t. I can barely see her teeth. Her mouth guard is in the way.