The ground floor at Barneys on Madison Avenue has always been a magical, twinkling place. It is reached via a great big door that revolves with a seemingly limitless flow of glossy hair and glossy skin and glossy nails and very expensive leather in the form of handbags and shoes.

Everywhere there are antique vitrines filled with striped Japanese socks, or gumball-size rubies direct from Jaipur, or watches from Hermès, or stacks of cashmere shawls so fine they could fit through any number of the diamond pavé rings that are displayed on either side of the door. There are vintage rose-gold earrings from Spain and there are elegant briefcases from a family-owned company in Milan.

It’s one of the places people go to celebrate something New York and big, like a promotion or an opening on Broadway or the closing of a major deal. It is also a place people go when they are rich enough not to need a special occasion to celebrate, or when they want to treat themselves to a pair of shoes (on sale or not)—or simply to a chopped chicken salad at Fred’s, the restaurant on the ninth floor where the patrons enact a version of New York life that is usually restricted to romantic comedies. As Sarah Jessica Parker once said: “If you’re a nice person and you work hard, you get to go shopping at Barneys.”

But like many of its clients, Barneys—founded by Barney Pressman in 1923—has had its ups, its downs, and its great many in-betweens, and it is, at right this very moment, engaged in that most New York of pursuits: a reinvention.

In 2007, the entire Barneys chain—six Barneys stores in the U.S., plus fifteen Barneys Co-Ops, which target a younger client with a smaller budget—was bought by Dubai’s Istithmar World for $942 million, including around $500 million in long-term debt. In 2008, Barneys CEO Howard Socol resigned, and the whole operation trundled along for several years without anyone in the top job.

But then, last summer, Mark Lee was hired as Barneys’ new CEO. Lee is a slim man with a trim haircut and a wardrobe of very well-made suits. His reputation is as golden as it gets in the fashion world: He’s spent his career in Europe occupying high-level positions at important fashion houses—Armani, Yves Saint Laurent, and, most recently, Gucci, where revenues went up 46 percent during his three and a half years as CEO. Lee is very much a businessman, but he’s the kind of businessman with taste: He was an early proponent of Stefano Pilati, now chief designer at YSL, for example. As Simon Doonan, who has worked at Barneys for 25 years as everything from spokesman to window dresser to general creative mastermind, puts it, “Mark Lee is very modern. He’s a very forward-thinking dude.”

Lee resigned from Gucci in 2008 and was enjoying a sort of quasi-retirement back in New York comprising Pilates, home renovation, and corporate boards (Tory Burch, Yoox). His longtime partner, Ed Filipowski, who is the co-president of the fashion-PR juggernaut KCD, lives here, and so do the couple’s two beagles. Lee, quite simply, wanted to come home. “I don’t mean to sound terrible,” he says, “but I’d worked for all of these great European brands, and there just weren’t American brands that I felt excited about.” But Barneys had always been on his list of dream jobs. He was offered a position there 25 years ago by Gene Pressman, grandson of the store’s namesake. That offer was made on a Friday, and when Lee asked for the weekend to think it over, it was rescinded. “Gene thought that if I was passionate about it, I would have accepted on the spot,” Lee says over lunch one day at Fred’s (named for Fred Pressman, Gene’s father). He slices his chicken Milanese into neat little bites. “So I suppose this is what Oprah would call a full-circle moment.”

A lot has changed since that long-ago offer. In these crazy economic times, the very highest end of things has remained very much up, particularly in places like China, but with global expansion has come a dilution of what luxury used to mean. Even at home, among all the Real Housewives, a name brand and a big price tag are no longer enough to qualify an item as exclusive. And now there’s the economy’s latest churn. “The 24-hour news cycle tends to play on the psyche of the customer,” Lee said last week. “It’s important we stay fine-tuned to the situation. We are always competing. Luxury customers are still shopping, but they are very thoughtful about purchases.” And presumably, they want something that the Jill Zarins of the world haven’t got. For Lee, this is the key to the success of the new Barneys. “The bigger luxury brands get,” he says, “the more that gives meaning to Barneys.” In order to attract the kind of customer Barneys is after, the kind of customer who helped make the store the cultural fetish that it is, Barneys has to concoct a universe in which expensive product is even more special, unique, worth it.

A Barneys matchbook ad.

The first thing Lee wanted to do was change the store’s awnings. For years, they had been cherry red, a nice contrast to the limestone of the store’s façade. (An idea Fred lifted from Paris’s Hotel Plaza Athénée.) But “when I close my eyes and think Barneys, the first thing I picture is that black bag,” Lee says. He means the shopping bag, with its elegant, well-spaced font. Black awnings went up in February. The image they presented to the passing throngs was maybe a little less friendly than the red; certainly the effect was sleeker. They meant business, those awnings. Fashion business.

But Lee’s primary mission was installing a new team.

Barneys has always organized its executives in a manner similar to that of the masthead of a fashion magazine, as a collection of characters whose judgments you’d trust. Part of the Barneys magic was that these people never seemed terribly concerned with the selling of things; the bottom line was almost beside the point. “Genereally loved the idea of creating a Bauhaus,” says Doonan. “He wanted to have lots of people working for him who were creative in their field; he was really excited by this idea of a group of creative people, the dramatis personae of this production called Barneys. Except that he sometimes got confused and called us his Bathhouse. But it didn’t matter. We knew what he meant.”

Lee kept a number of key people, like Doonan, who became creative-ambassador-at-large, and Tom Kalenderian, who has been with Barneys for 32 years and now oversees men’s and home. He also left many of the store’s business executives in place. But some of its most visible characters were out.

One was Julie Gilhart, who had been the women’s fashion director for eighteen years. Gilhart was known for unearthing young talent—she famously discovered Proenza Schouler—and, more recently, for her interest in ecofashion. Exiting Barneys, Gilhart left town and promptly burned 25 years’ worth of her diaries in a Hawaiian honomopopo ceremony on a Mexican beach.

Next to go was head merchant Judy Collinson, who was known for wearing ankle socks, cardigans, and cat’s-eye glasses and generally looking a great deal like a librarian from a Maira Kalman print: quirky but sensible. Collinson had always maintained a dignified silence, scribbling away in the front row at fashion shows and staying out of the press.

Lee made his choices quickly: He went immediately to Daniella Vitale, the former president of Gucci America, to take over the position of head merchant for women’s fashion. Vitale has long legs and long hair and a manner that is simultaneously relaxed and intense. “Mark and I have known each other for twenty years, and we have always been very aligned,” Vitale says one summer afternoon. She occupies a corner office at Barneys corporate HQ and is wearing, today, an immaculately pressed white cotton shirtdress, bare legs, and sandals with a high wooden wedge for a heel. “Barneys has to stand for something; it has to feel different,” she says. “This is shopping as a cultural event.”

Vitale accepted the job in late November—prime Barneys selling season—and began spending her weekends in the store watching people shop. “I kept seeing the same people in the store over several hours. They’d come in for lunch at Fred’s, and then I’d see them in shoes, and then wandering around in men’s. People were coming to the store as a destination. Couples were coming together, and families. They were coming in to have an experience.” As the holiday season gave way to January, Vitale noticed that the clientele became more international: tourists who seemed to treat the store as a landmark worth seeing, like MoMA.

For all the time she spent inside the store, Vitale’s top priority quickly became sorting out the Barneys website. Her goal was to get the online merchandise to match that of the Madison Avenue store. Earlier iterations of the website had been strong on accessories (shoes, jewelry, and bags) but weaker when it came to ready-to-wear. Vitale persuaded vendors like Marni, Balenciaga, and Ralph Lauren to sell online (she’s still working on Alaïa) and saw an 80 percent increase in web sales. “There’s always been this idea that online is not a luxury experience, but this summer we sold a $25,000 piece of jewelry online.” Vitale smiles. “That,” she says, “is a luxury experience.”

But Vitale was also thinking about those customers wandering the floors of Barneys for hours. She added a component called “The Window” to the site. It’s a blog, a space where you can learn that Barneys head of marketing and communications Charlotte Blechman brings Astier de Villatte candles (available in the ninth-floor Chelsea Passage) as house gifts, and that the store’s new creative director, Dennis Freedman, wants to teach his dog to back-flip off the diving board before summer’s out. It’s retailer as tastemaker, as incredibly chic friend lending advice on how to live.

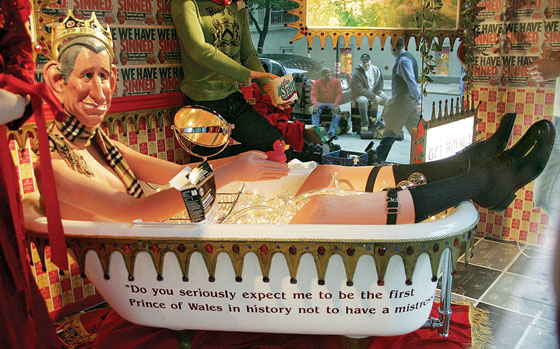

A whimsical 2005 window installation by Simon Doonan. Photo: Eth Wenig/Reuters/Corbis

“The digital and the physical experience need to be integrated,” Vitale says, and so a series of iPads are being installed in the store (launching on the first and eighth floors) so that salespeople and customers can use them as part of what Vitale calls the “selling ceremony.” Say you’re interested in Céline. A Barneys salesperson might well appear with an iPad loaded up with an interview with the designer, Phoebe Philo, or a street-style picture of Barneys’ new fashion director, Amanda Brooks, in a Céline dress, or just a comprehensive inventory of all the Céline clothing, shoes, and bags Barneys has to offer at that moment.

Vitale has also been tasked with lining up exclusive product for the store: L’Wren Scott handbags, for example, or women’s suiting by the designer Alexandre Plokhov, who used to design the menswear line Cloak. Barneys will become, this fall, the only store in America to carry Walter Steiger shoes (other than Walter Steiger). It will also offer an exclusive menswear collaboration with agnès b.

Hanging on the wall in Vitale’s office is a blowup of an old Barneys ad, a painting by the French artist Jean-Philippe Delhomme. In the painting, a woman models a dress for her friend. The tagline, written by Glenn O’Brien, GQ’s style-advice columnist, reads: “Nina knew David would eventually weaken.” Outside Vitale’s office is another iconic moment in Barneys advertising: Linda Evangelista modeling a hat. Next to her is future boyfriend Kyle MacLachlan wearing a lobster on his head. Part of the Barneys ethos has always been this ability to laugh at the whole thing, to allow the customer in on the joke—or at least to acknowledge that its customer is no rube. In a way, the store glamorized shopping by quasi-ironizing it. In the mid-nineties, the store’s tagline under Doonan became “taste, luxury, humor.”

“Barneys has to stand for something. It has to feel different. This is shopping as a cultural event.”

Now, however, the store will be a little less whimsical. Times, after all, have changed. “We’re still going to have humor,” Vitale says, “we’re just going to have it in a very refined way.”

Lee’s next hire was Freedman, who was the creative director at W magazine for almost twenty years, where he was devoted to the intersection of high fashion and high art, and always happy to push at the edges of things: It is Freedman who once published a photograph of Tom Ford sanding another man’s bottom. At Barneys, Freedman’s office sits one floor above Vitale’s, but where hers is all clean windows and views, Freedman’s is cavelike. He’s painted the walls a dark gray and taken efforts to dim any natural light. “I hate light,” he says cheerfully. “Hate it.” Freedman is tanned from weekends on Long Island. In the low light his teeth look almost electrically bright.

He explains that he had never really considered working in retail, but then he had an important conversation with a friend. “I was talking to [gallerist] Andrea Rosen about it, and she told me that Felix Gonzalez-Torres once said, ‘Barneys is my bodega,’ and those words just really resonated with me. This great and powerful artist said ‘Barneys is my bodega.’ What could be more inspiring than that? For me, that’s my tagline.”

Freedman goes on: “[Gonzalez-Torres] loved Barneys. He couldn’t say that about any other store. And that gives me a sense of responsibility.

“Look,” he says, “I understand that I am not doing personal work. This is commercial. But I enjoy the process of limitations. Every window is not about clothes, it’s about a way to show creativity. We’re creating an identity that is part of a whole lifestyle. I’m more interested in wit than I am in humor. Irony isn’t as important as a certain kind of honesty.” Freedman produces a stack of catalogues—his first for the store. For the women’s mailer, he asked Carine Roitfeld, the former editor of French Vogue, to create a catalogue featuring the store’s highest-end clothing. Roitfeld cast a list of 28 fashionable people, including Naomi Campbell. She also cast herself, her daughter Julia, her son Vladimir, and Giovanna Battaglia, the Italian stylist who goes out with Vladimir. The photographs are by Mario Sorrenti, and below each is a caption: “I once saw Vanessa [Traina] at a dinner in Paris with her mother Danielle Steel. She was wearing Balenciaga, and I thought, Who is that girl?” And so on.

For the men’s designer catalogue, he sent photographer Juergen Teller to traipse around East London with Andrej Pejic, a male model (see here) who has also quite convincingly modeled women’s clothes. Freedman did a second, more traditional mailer for menswear with less fashion-forward clothing on less fashion-forward men—a collection of ruggedly handsome bartenders.

Daphne Guinness in the window this past May. Photo: Neilson Barnard/Getty Images for Barneys New York

Freedman is also overseeing the store’s renovation: Where Doonan once decorated the dressing rooms of the Co-Op with a multicolored arrangement of Tic Tacs, Freedman is streamlining everything with high-end finishes and mega-technology. Even his stunts are sleeker, the sort of elaborate projects that might have once appeared in the pages of W.

His very first window installation, this spring, starred Daphne Guinness. The heiress-muse got dressed for the Met’s Costume Institute ball in one of the Madison Avenue windows, vamping and mooning her way into a pale-gray ostrich-and-duck-feather gown by Alexander McQueen. Freedman has already begun to work on Christmas: Gaga’s workshop is the plan, and the Lady herself will function as an alt-world Santa Claus, enlisting God-knows-what to serve as her elves and then selling for-Barneys-only merchandise that she designs in collaboration with Nicola Formichetti in a GagaZone on the fifth floor. It’s not going to be as edgy as some of Gaga’s videos, and some of the proceeds will go to charity. “Simon explained something to me,” Lee says, “and that’s that if your fall windows are Antonioni, your Christmas windows need to be Billy Wilder.”

A brief history of the store goes like this: First, Barney Pressman hocked his wife’s engagement ring for $500 to get things off the ground. In the beginning, Barney’s (throughout its history the store has often used the apostrophe) business was discounted men’s suits, and Barney himself didn’t care much about the aesthetic environs in which he sold them. But he had a knack for advertising (“No Bunk, No Junk, No Imitations”) and hype: He once sent comely ladies out in barrels to entice customers on the street. Then Barney’s son Fred began to get involved. Fred shared his father’s knack for publicity and customer service (free parking for all those customers from Great Neck and Darien who came to shop at Barneys on 17th Street and Seventh Avenue) but also had an eye for European fashion and high design. Slowly, Fred began to transform the brand into something more glamorous: In the seventies, he introduced designers like Armani to New York. He began to carry women’s merchandise, and to offer Perrier in the canteen. Then Fred’s son Gene got involved, too, and Barneys went even higher-end, with women’s merchandise overtaking men’s and plenty of floor space devoted to the Japanese avant-garde. There was an early AIDS fundraiser, in 1986, at which Madonna worked the runway in a denim jacket. It was the ultimate merger of uptown and down, and exactly where fashion wanted to be at just that moment.

The members of Barneys’ current team are all veterans of this moment: Doonan remembers seeing Andy Warhol and Jack Nicholson shopping together for socks. Lee remembers blowing a good part of his student-loan check on a purple-and-red Norma Kamali sleeping-bag coat.

In the late eighties, Barneys began opening stores around the country, exporting New York taste to the provinces. Sometimes, as in the case of Beverly Hills, this worked. Other times, less so. Trouble in Dallas occurred, for example, when the beauty salon refused to accommodate requests for big hair.

Back in New York, the new flagship, on Madison Avenue, opened in 1993. It was the largest specialty store to open in the city since 1929. Barneys had made the final transition to luxury, though it would seek bankruptcy protection three years later.

One night in July, the ground floor of that store was partially closed off for construction, but bits of the new Barneys had begun to appear. Gone was the glittering mosaic floor, replaced by slabs of cool gray stone. The place was already a more hard-core version of itself: luxury incarnate. A maze of temporary Sheetrock led to the elevators, and whoosh! Up on the fifth floor, Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen were hosting a launch party for their new handbag collection. Their label, the Row, makes clothing that is simple in shape and luxurious in quality and that, in spirit, calls to mind the work that Calvin Klein did at the height of his reign. It is very, very expensive (the handbags range from $2,350 to $39,000), and it has one of the highest sell-through rates in the store. It is, as Daniella Vitale says, “very Barneys,” in that it is “more understated than overstated. More minimal than maximal.” None of Barneys’ direct competitors carry the line.

Vitale is all polish in a miniskirt, heels, and a tuxedo jacket by the Row. Lee and Freedman are in dark, elegant suits. All of them move through the room purposefully, with confidence. Mary-Kate Olsen appears in a robin’s-egg-blue jacket-dress. “We bought that in the blouse version,” Amanda Brooks assures Lee, before he’s even asked. Lee nods. And then he notices Elizabeth Olsen, the twins’ younger sister and this year’s Sundance breakout starlet. “Fendi heels,” he says approvingly. “Fourth floor.”

After the cocktail party, the team heads over to the not-yet-open-to-the-public Crown restaurant, on East 81st, for dinner. As dessert is cleared, Doonan and Freedman wander out to hail two of the taxis racing up Madison Avenue. But Freedman is quickly distracted. “What is this?” It’s a window full of beautifully lit Venetian glass in periwinkle and dusty rose and cherry red—it’s the uptown outpost of De Vera, the extraordinarily high-end Crosby Street curiosities shop. “That is vintage glass!” he exclaims and presses his face close to the window, craning to see each bit. “Amazing.”

On the corner is Vilebrequin, maker of the popular, expensive French swim trunks. Both men immediately go silent, Hawaiian prints reflecting in the pupils of their eyes. They’re studying the patterns, the display, the angles of the light, and then they begin to debate the merits of the various swim trunks Barneys currently has for sale. “Elastic can give you that little … ” Doonan gestures to his midsection as if to indicate some male version of a muffin top.

“You’ve got to try the Orlebar Brown” trunks, Freedman says. “No pooch!”

“No pooch!” Doonan agrees, and then he smiles. “We’re retailers,” he says. “All we’re ever really thinking is, are you being served?”