It is hard to keep up with the politicians, but the New York Sports Sex-Scandal Hall of Fame has an impressive roster, back to when Babe Ruth reputedly missed half the 1925 season with the clap. Patrick Ewing, Mike Tyson, Lawrence Taylor, David Cone, Isiah Thomas, and Marv Albert are just a few of the city’s best-known sports figures to splat across the back page on accusations ranging from statutory rape to bull-pen masturbation and cross-dressing toupee loss.

However, even if no center-field monument will commemorate it, New York’s all-time oddest sports sex scandal came to light during spring training in 1973. That was when two Yankees pitchers, Fritz Peterson and Mike Kekich, 40 percent of the team’s starting rotation, called a press conference to inform mind-boggled newsmen that they had traded families. This included wives, children, and pets.

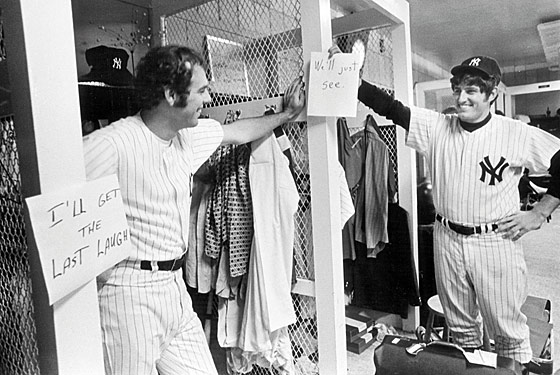

“Don’t make anything sordid out of this,” said the 31-year-old Peterson, a twenty-game winner in 1970 who was then living with Kekich’s wife, Susanne, in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey. The 27-year-old Kekich agreed. “Don’t say this was wife-swapping, because it wasn’t,” Kekich said. “We didn’t swap wives, we swapped lives.”

“It was hard to know whether to laugh or cry,” says Phil Pepe, Daily News Yankees beat writer at the time. “George Steinbrenner bought the team weeks before, but mostly he walked around pointing at guys whose hair he thought was too long. Ralph Houk, the manager, sat there smoking a cigar, trying to keep a straight face.”

Thirty-eight years later, despite holding steady as ESPN.com’s “sixth most shocking moment in baseball history,” the Peterson-Kekich “Trade” has been largely regarded as a curio of the game’s wacky period immediately preceding free agency, a time that included Charlie Finley’s mule and Dock Ellis’s supposedly pitching a no-hitter while under the influence of LSD.

I was thinking about the Trade as I made my way to Yankee Stadium one recent Friday night. Once upon a time, this was one of the great rushes of city life—the IRT lurching up from the tunnel to reveal the fortress stadium, a green swath of outfield grass fleeting by the window as the train pulled into the 161st Street station. Now, with the Big Ballpark’s $1.5 billion simulacrum hauled up River Avenue, the first thing you see is a multilevel parking lot where they charge suburban fans $35 per car.

It was in this frame of reference that I recalled a series of articles I’d read in the paper about how Ben Affleck was preparing a long-delayed film project based on the Peterson-Kekich affair. Affleck was working on the script with his brother, Casey, “Page Six” said. Matt Damon was rumored to be involved. This raised local hackles. “Where do Boston dweebs get off making a movie about a Yankee anything?” one talk-show caller growled. In an attempt to make nice, Affleck said on MTV that he had nothing against the current Yankees players, who seemed “like good guys.” However, as for the Yankees “as an institution,” Affleck felt nothing but “disdain” and “contempt,” to which he added, “guys (bleep)ing each others’ wives—that’s those Yankees.”

As someone whose trade-unionist grandfather cursed the Yanks as the team of the plutocrats, I understood why a film about the Trade would appeal to those less-than-enthralled by the pinstripes. The Yankees won a numbing fourteen pennants in sixteen years, from 1949 to 1964, but by the early seventies, baseball in the already burning Bronx was moribund. With the Savage Skulls in the street and Reggie Jackson still a distant wet dream, the Yanks were mired in the “Horace Clarke Era”—named for the .256-hitting second-baseman known for bailing out on the double play. In 1972, the year before Steinbrenner bought the greatest franchise in sports for the E. J. Korvette markdown of $10 million (!), a mere 966,328 people, the fewest since 1945, came to the rusting hulk that Ruth built.

Into this desultory environs arrived Fritz Peterson and Mike Kekich, an odd couple of left-handers with Beatles cuts and paisley shirts. Peterson was the funny one, the clubhouse cutup. He put talcum powder in Joe Pepitone’s hair dryer and printed up fake newspapers with stories about how the Yankees plane had crashed and he was the only survivor. Once, the right-handed Thurman Munson sent away for a holster for his .357 Magnum; Peterson switched the order to a left-handed holster. When Munson sent away for a refund, Peterson got in touch with the company and asked them to send Munson a booklet on how to draw a gun left-handed. On the mound, however, few had better control. In his twenty-win 1970 season, Peterson pitched 260 innings and walked only 40 batters, a remarkable ratio. Of pitchers making a requisite number of starts at the old stadium, Peterson has the lowest ERA—better than Whitey Ford, Lefty Gomez, and Red Ruffing.

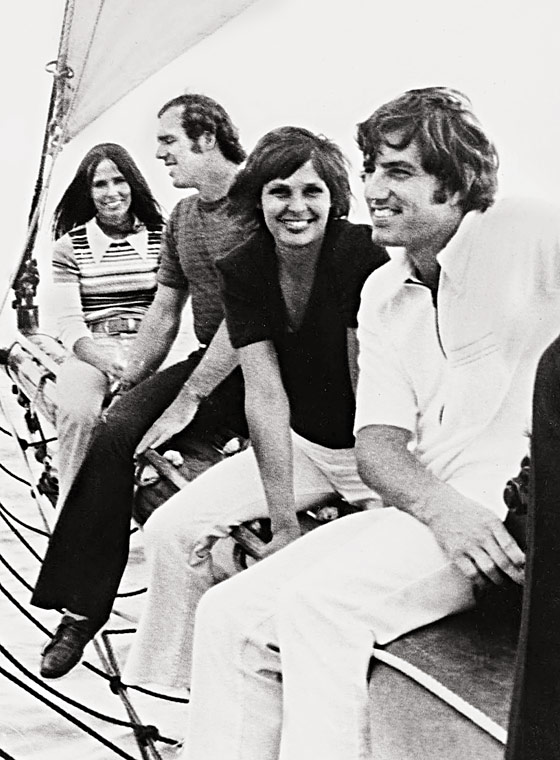

Mike Kekich was a different story. Tan, tall, and tooling around in a Route 66–era sports car, the laid-back, earnest Kekich fit the image of a Cali-bred Roy Hobbs. Touted as the second coming of Sandy Koufax when the Dodgers gave him a 50-grand signing bonus, Kekich could throw the ball through a wall but couldn’t locate the plate. Considered “a little goofy” by Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, Kekich was traded to New York, where he became the roommate of Fritz Peterson. Fritz and Mike, along with their spouses, Marilyn Peterson and Susanne Kekich, grew close. It made sense. Both couples had young children about the same age, and all four had some higher education, which set them apart from baseball’s still-ambient redneck culture.

“We had a tremendous amount of affection and compatibility all around,” Mike Kekich said. Fond of long, introspective conversations, Kekich was drawn to the thoughtful Marilyn Peterson, while Fritz, always in the moment, paired off with Susanne, a former cheerleader and cross-country runner. Gradually it became apparent to all four that perhaps they were married to the wrong people.

“By American standards, I had a good marriage,” Kekich said. “But I wanted a great marriage. I was idealistic, I guess.”

The Trade couldn’t happen today, said a fan: “What wife with a $14 mil player is switching to a $4 mil player?”

As one version of the story goes, the Trade was arranged on July 15, 1972, outside the home of Post Yankees beat writer Maury Allen in Dobbs Ferry. Back then, it was not unusual for ballplayers to spend time with reporters. They traveled on the same planes, stayed at the same hotels, made about the same amount of money. That evening, however, something was up, Allen thought. Marilyn Peterson, pretty, petite, and “sophisticated,” usually wore a blonde wig because that’s the way Fritz liked it. On that night, she arrived with her natural hair color. Allen thought she looked sweeter, younger, looser.

Only weeks before, Marilyn had spoken with Allen’s wife, asking her how many times a week it was normal to have sex. The implication was that Fritz was a somewhat reluctant bedroom partner, at least as far as Marilyn was concerned. As Allen later wrote in his book All Roads Lead to October, Susanne Kekich, whom he describes as “a tall brunette—athletic-looking and aggressive,” seemed to be “competing” with Marilyn for Fritz’s attention. Hours later, Allen and his wife heard the Kekiches and Petersons still in the driveway, supposedly discussing the fine points of the swap. As dawn approached, the two couples, now realigned, went off in separate cars, agreeing to meet at an all-night diner in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Fritz and Susanne had already finished eating breakfast when Marilyn and Mike arrived, two hours later.

By their spring-training press conference, Kekich and Peterson were hardly speaking to each other. Much had happened in the interim. The couples did “swap lives,” moving in with each other’s spouses in the fall of 1972, with differing degrees of success. Peterson and Susanne Kekich were happy. Kekich and Marilyn Peterson were not. The physical attraction between Marilyn and himself was strong, Kekich would say, but since they were “born under the same sign, we sometimes butt heads. She and I are on a higher pitch in our emotions.” Kekich claimed everyone had agreed that if any of them were unhappy, the entire deal was off. Peterson said they had already tried that (the couples had attempted to reunite for a time) and it hadn’t worked.

In a statement, Peterson said he and Susanne were both now “free people” with “free minds.” It would have been perfect if things worked out for everyone involved, “but I don’t feel guilty.”

Kekich cut a far more sunken figure. The terms of the swap dictated that the kids would stay with their mothers. But now Marilyn Peterson was taking her children to her parents’ home in Illinois. His daughters living with Susanne and Peterson, Kekich was alone. Calling himself “one of the biggest soul searchers around,” Kekich said he would break up his family only “for love far greater than any I have ever known.” Now he was “dubious” such a love existed.

Asked if he expected to be traded, Kekich said, “I’m here. We’re still teammates. I only want to be where Fritz is.” It was “the only way I can be sure of seeing my daughters.”

This was not to be. After pitching fourteen innings for the Bombers in the ’73 season (walking fourteen batters), Kekich was dealt to the Cleveland Indians. Still a Yank, Peterson finished the season with a dismal 8-15 record and was also shipped out, to Cleveland, though by that time Kekich had already moved on, to Japan. Still, when it came to the Trade, Peterson was generally considered to be the winner. After all, he and Susanne are still married today, with children of their own. This result was predicted by Dr. Joyce Brothers, famed TV psychoanalyst. “It’s very rare that a four-way swap ever works,” Brothers said.

I’d been trying to talk to Fritz Peterson for a couple of weeks, without much success. In 1970, Peterson won the “Good Guy” award, given to the New York sports figure judged to be the most cooperative with the media. But now, nearing 70, with prostate cancer, after a fitful post-player’s life that included stints as an insurance salesman, blackjack dealer, and hockey play-by-play guy, Peterson was living in “semi-hiding.” Besides, after long opposing a film version of the swap, he had signed on as a consultant to the current Warner Bros. version. Peterson was looking forward to Ben Affleck reenacting his best locker-room jokes but wary of saying anything to jeopardize the movie’s getting made.

Eventually, Peterson did reply to a series of e-mailed questions, writing that “It was different being a Yankee. It just felt special” and that he never had any trouble with Steinbrenner over the family swap. In fact, Steinbrenner was one of his biggest supporters. “He was hoping I’d be the comeback player of the year in 1974.” Meanwhile, his marriage to Susanne has remained solid. “Thirty-eight years and we are still crazy in love.” Peterson was more eager to talk about his recent book, Mickey Mantle Is Going to Heaven. In what has to be one of the stranger sports memoirs, Peterson presents a series of breezy monographs on former teammates like Mantle, Thurman Munson, and his semi-mentor and Ball Four author Jim Bouton. Then, at the end of each chapter, the left-hander, who says he found faith at the end of his baseball career, muses about the individual’s positioning in the afterlife. Some Yankees, like Mantle and Bobby Murcer, by virtue of their acceptance of Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior prior to departing this world, will be “first-round draft choices,” i.e., immediately join God’s elect in heaven. Other people, like Maury Allen, whose book Peterson says contains “43 incorrect facts or statements (mistakes)” about the Trade, will have to take “a dip” or a more prolonged “swim” in hellfire. Peterson’s ad-hoc eschatology has not sat well with all his subjects. Jim Bouton, credited with the best Trade line—“I can see trading your wife, but the dog?”—said, “Oh, Fritz. Did you ask him if I was still going to hell?”

As for the final dispensation of Mike Kekich’s soul, Peterson, who says he is working on a new book titled Joe DiMaggio Is Going to Hell, takes a measured approach. Noting Kekich’s admirable qualities, including his fearlessness as a sky- and skin diver who once “[chased] down a manta ray as big as a car 25 feet down,” Peterson writes he’s “afraid” that Kekich will be taking “a dip,” or maybe even “a swim” in the “lake of fire.” The immersion could be quite extensive, Peterson writes, because even if everyone will go to heaven eventually, the fact that Kekich was “pretty bullheaded” did not bode well for his ultimate salvation anytime soon.

I wondered what Mike Kekich felt about having his eternal fate arbitrated by his less-than-beloved co-star in baseball’s reigning sixth-most-shocking moment. Several phone calls and e-mails sent to an Albuquerque real-estate office where Kekich was said to be working went unreturned. According to “Page Six,” Kekich was so “panic-stricken” about the upcoming film that he had “moved away and has a new identity.” It sounded like a perfect existential movie moment: Mike Kekich, the failed California phenom, holder of the short straw in the Trade, now on the run from the specter of Matt Damon immortalizing the most humiliating incident of his life.

Your heart went out to the guy. A few years ago, he told an interviewer that his baseball career went into “a black hole” after the Trade. He lived an itinerant life, pitching in Japan, attending medical school in Mexico but never becoming a doctor. The man was obviously a dreamer. Even in the scandal’s aftermath, Kekich wistfully told a Daily News reporter, “I can’t tell you how perfect it would have been if it had worked.”

Up at the stadium, the details of the Fritz Peterson–Mike Kekich family swap are hazily recalled. Everyone says it’ll be a great movie, though it is difficult for fans now to get their minds around how it could have happened. Could two current Yanks pull a Peterson-Kekich?

“Money would come into it,” one writer said. “What wife with a $14 mil player is switching to a $4 mil player?” Still, even if there were votes for the tandem of A. J. Burnett (“His wife has biker tattoos”) and Nick Swisher, most said any present-day trade would have to include the juicy pairing of Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez.

“Got to be A-Rod and Jeter; they’re always sleeping with each other’s chicks anyway,” said one man seated in a $300 seat a few rows behind the guarded “moat” that keeps riffraff like him from invading the $500-plus “Legends” area. “They’re not married, but they’ve got girlfriends. A-Rod gives Cameron Diaz straight up for Minka Kelly [Jeter’s girlfriend]. Cameron’s a great actress, but Minka is way better-looking. That’s even value.”