Denial is powerful. It can be a crucial coping tool when experiencing loss or trauma, but it also can unmoor you from reality. From the time I lost most of my left arm in February, I was living in that parallel universe, one where I’d power through, barely acknowledging the amputation—until I went for a run on the sunny afternoon of April 6.

It was nothing more than a slightly uneven sidewalk that took me down. No problem for a runner with two arms. In fact, this particular sidewalk is right behind my home, and I had negotiated it uneventfully for years. But here are two things you need to know about life after an arm amputation: First, your center of gravity changes dramatically when you are suddenly eight pounds lighter on one side of your body. Second, while my arm may be missing physically, it is there, just as it always has been, in my mind’s eye. I can feel every digit. I can even feel the watch that was always strapped to my left wrist. When I tripped, I reached reflexively to break my very real fall with my completely imaginary left hand. My fall was instead broken by my nose, and my nose was broken by my fall.

Lying on that sidewalk, moaning in pain, I reached the end of Denial River and flowed into the Sea of Doubt. It finally dawned on me in that instant that I was, indeed, handicapped. That may not be the term of choice these days—“differently abled” or “physically challenged” may be de rigueur—but as I touched my bloody face, feeling embedded chips of concrete in the wounds, “handicapped” sure seemed to fit.

The woman I was passing on the sidewalk when I fell took one look at me and cried out in panic to her husband: “My God, what’s happened to his arm?” “It’s gone,” I said. “But don’t worry, that didn’t happen today.”

Truth be told, my arm never did feel “gone.” The whole thing is such a fluke I have a hard time making sense of it. Frankly, I’m not interested in revisiting the excruciating details (more denial!). But the sound-bite version of my gory story is this: I was on a reporting trip in the Far East, first to Japan for a story about the Fukushima reactor and then to the Philippines for one about genetically modified rice. As I was packing up my TV gear, a heavy Pelican case of equipment fell on my left forearm. What began as a fairly bad bruise evolved, over a couple of days, into something life-threatening: acute compartment syndrome, which blocks blood flow. When I got to a doctor in Manila, he recognized the problem and sent me in for emergency surgery. He tried to save the arm, but it was too late. It was a life-or-limb decision.

When the anesthesia receded and I rejoined the world of the living, I was convinced that the doctor had saved it. It was a good thing drugs were still coursing through my veins when I took my first look. No hand. No forearm. No elbow. All of it gone. No, the surgery had not gone well at all.

I had been traveling alone, hiring local drivers and fixers. As an independent TV producer, I am always looking for ways to save a few bucks, but I have also always been a do-it-yourself kind of guy, and I truly love shooting my own stories. The lifestyle of being a “one-man band” reporter suits me just fine. That ethos is also part of why I am not very good at reaching out to others for help. But beyond that, I grew up in a boozy, dysfunctional household that left me with a core of self-reliance and a compulsive desire to fix other people’s problems that is not healthy.

This might help you understand the decision I made, while I was in that Philippine hospital and then in a hotel room, that many people have second-guessed: I didn’t let anyone know what had happened to me for more than a week. I imagined an armada of flights heading my way and imagined myself worrying about their travel, their flights, their hotels. All I really wanted to do was manage the pain and think. Maybe I could just heal a little, then sneak back home. You know, denial.

Instead of calling in the cavalry, I enmeshed myself in work, writing my Fukushima stories. So the first real obstacle I encountered in my mono-mano life was the QWERTY keyboard. I hunted and I pecked and then started leaning heavily on voice-dictation software (as I am right now).

I had worked hard on the Fukushima stories and felt they were important. They needed to be ready in time for the anniversary of the meltdowns. But there was also a practical urgency to the matter: As a freelancer, I eat what I kill. I had spent a lot of money on travel, and on hiring local help. I had to deliver the completed work or take a huge loss. So I wrote my scripts, and when friends and family checked in, I acted as if all was well. When they found out later, most of them understood my decision.

As soon as I got back, I told my kids in a Skype conference call. My 21-year-old son is studying in Beijing. My daughter, 19, is at college in North Carolina. I dreaded breaking the news to them, but they expressed love, support, and gratitude that I was alive. It brought tears to my eyes—mostly because I was just so proud of them.

My other big worry had to do with my livelihood. I am in a business where looks matter, and I wasn’t aware of any one-armed TV correspondents. Would my empty sleeve end my on-camera career?

At the PBS NewsHour, where I am treated like family, they were just as accepting and supportive as my own children. When I asked if I should shoot and edit around my disability, my boss told me, “No one cares. Just be your smart, engaging self.”

And then came a call from the old girlfriend who had ditched me: CNN. We had been in a committed relationship for 17 years when she dumped me in December 2008. It was a bitter breakup, but I had moved on. Now she was obsessed with the missing Malaysian airliner, and I am a pilot and aviation geek. I was the right guy—once again.

They wanted me on the air as fast as possible. No one gave a damn that I could count only to five on my fingers. I called it my “Vindication Tour.” It would’ve been sweet enough even if I still had two hands. But for a newly minted amputee unsure of my future, it was the best medicine imaginable.

I’d always heard amputees talk about the stares and the acute awareness of being viewed as different. During my first shoot for the NewsHour with one arm, I was wearing a blazer when I met a researcher I was to interview. She left the lab, and I took my jacket off. When she returned, it was a good thing she wasn’t sipping her coffee, because she would have offered up an amazing spit take. As we both looked at my stump, I shrugged and said, “It happens.” She smiled and nodded and then we pressed on. It didn’t really bother me for some reason—perhaps because of the honesty of her reaction. What makes me more uncomfortable is when I notice people consciously looking away. Is that pity? Revulsion? On the sidewalks, I look straight at people looking at me, and lots of times, they smile. Maybe I am still attractive. Or maybe I’m a freak.

My girlfriend was the one most upset about my silence in the Philippines. When she saw me for the first time, we fell into a long embrace. With tears welling, I asked her if she could still love me despite my diminished body. She caressed and kissed what is left of my arm. I took off the bandage and showed her the stitched wound. She kissed it.

The mono-mano life is more manageable than you might think. If you were to tie one hand behind your back and go through your day, you could accomplish just about everything. It takes longer, but it can be done.

There are some things that make one-handed life easier. I use a cutting board that sits on suction cups and has a lip and some spikes that can hold a slice of bread or a piece of fruit in place. I have a one-armed bottle opener, a mezzaluna (a knife shaped like a half-moon), a fork with a knifelike edge called a “knork,” a hook that allows me to button and unbutton my one cuff, some very sticky material called Dycem that can hold a jar steady on a counter, and, of course, an electric can opener.

I’m also learning to use a prosthetic arm. The one I wear is body-powered, meaning I wear a harness and move the elbow and hand by moving my stump forward, broadening my shoulders. The basic technology dates back to the 16th century. By comparison the split hook that is my new hand is a modern marvel, patented in 1912.

In my job as a science and technology correspondent, I have covered some of the advances in prosthetic technology in recent years. They are remarkable. But now that I am looking as a customer, I see shortcomings. The devices rely on actuators, which in turn rely on batteries. That makes these arms very heavy, less reliable, and not weatherproof. To make some of them work well, doctors need to move nerves to better connect them with sensors inside the robo-arms. Replicating what the human hand does is a very difficult problem for engineers, much harder than making an artificial leg. I have learned, though, that one hand—with all its dexterity, sensitivity, and opposable-thumb efficiency, along with something much more crude that has the simple ability to grasp—is all you need. For now, the split hook I wear is working well. I’m pretty sure that it’ll allow me, eventually, to return to the cockpit.

My prosthetist assumed I would like to have a cosmetic hand, one that has no real function but looks like the real thing, and so he made a mold of my remaining hand. An artist who produces fake wounds in Hollywood created a clear silicone mirror image. Then she sat with me for six hours, painting it, even embedding bits of hair snipped from my right arm. The result is haunting, and I don’t like looking at it. I’m not sure whom I would be wearing it for. I don’t feel the need to pretend or to make my presence easier on others.

The biggest problem I cope with is phantom pain. My arm has become a ghost, immobilized as if it were in a sling—which is where it was the last time I saw it. If I concentrate, I can move my imaginary fingers. The arm feels as if it’s been asleep and the circulation has just begun once again. First thing in the morning, it’s actually a pleasant, painless feeling. My arm is suspended, almost as if it is weightless. But as the day goes on, it feels as if it is progressively bound tighter and tighter, to the point of excruciating pain. In addition, my fingers often feel as if they’ve been jolted with surges of electricity.

Doctors don’t really know how to treat pain in a part of the body that no longer exists. I’m taking a fairly heavy dose of Neurontin, which is also used to treat epilepsy, restless-leg syndrome, and insomnia. I’m not supposed to stop taking it abruptly, so there’s no way for me to test exactly how well it’s working. Acupuncture, massage, and exercise help. So does marijuana. I’ve also tried mirror therapy, first pioneered by the UCSD neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran. I place a mirror on a table perpendicular to my chest and sit up close, so it looks as if I have my missing left hand back. If I concentrate on moving my phantom left hand and matching its movements with my right hand, my brain is tricked into thinking that its old internal map is still complete. The movements alleviate a lot of my phantom pain.

How this works is mysterious. It’s not psychosomatic, as was once thought. Recent research suggests that our brains map out our bodies, like a neural schematic of switches, channels, and routers in a complex communications network. When there are suddenly no circuits feeding areas of the brain that control a newly missing limb, the nerves in another part of the body will attempt to fill in the gaps. So now when I scratch the back of my cheek near my ear, or the bottom of my heel, or my chest near the sternum, I feel a sensation in the fingers of my missing hand. And even odder than that, when I take a drink of something cold or hot, it feels as if it is flowing directly into my phantom arm. I also get a tingling feeling there when I’m having sex.

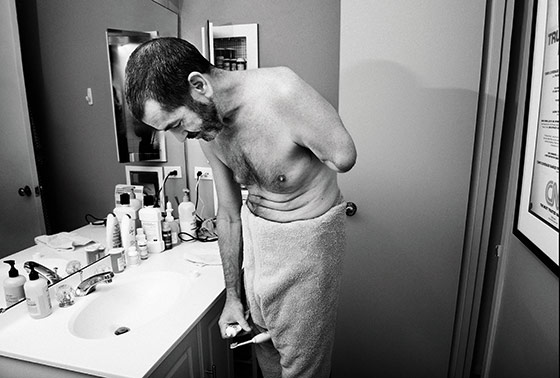

Besides the pain, the biggest inconvenience about being one-armed isn’t any individual task, but in the aggregate. I had a very busy, overbooked life before I lost my arm. Now each thing I do takes longer—sometimes much longer. Consider what it takes for me to get ready in the morning: In the shower, I wear a wash glove and put bottles between my thighs to squeeze out body wash and shampoo. To wrap a towel around my waist, I must grab a corner with my teeth and hula-dance a little so that I can grab the other end with my arm, bring it back around, and tuck it in. I use my big toe to move the lever on a fingernail clipper. I button the right cuff of my shirt before I put it on so that I can slide my hand through. The other buttons can be managed with one hand, but each takes more time (especially the top one). I learned how to tie a tie from a one-armed guy who’s made a great YouTube video.

I could tell you about toasting a bagel, opening a new box of cereal, or changing the trash bag, but you get the idea. A morning routine that used to take 30 minutes now lasts more than an hour. At the end of each day, I have always done less than I expected to do. This makes me cranky. I have, grudgingly, learned that it is not always good to try to do everything yourself. And I am asking for help much more than I ever did before. Guess what? People want to help. Especially other amputees, who have been generous with ideas and experiences.

Two months to the day after my accident, I went to see a therapist for the first time in my life. I didn’t know where to begin. We discussed loss and resilience and the will to live and adapt. But when I started talking about the outpouring of love and support that I had received since my accident, I began weeping uncontrollably. I realized that for the first time in my life, I was truly letting love into my heart. Losing an arm has connected me to others in a way I have never felt. Yes, I have suffered a tremendous loss, but in a way, I feel as if I have gained much more.