At 30, Gabriel Calatrava is an aspiring architect with a distinguished surname and a restricted clientele consisting mostly of immediate family. It is a close-knit clan, headquartered in three adjoining Park Avenue townhouses. Like his celebrated father, Santiago, the creator of deluxe white bridges, stations, and museums, Gabriel has one foot in engineering and the other in architecture. He has spent five years working in the family business, commuting from right next door; his parents have an equally brief walk to the office from the other side. (His mother, Robertina, is also Santiago’s business partner.) If he wants to visit his older brother, Rafael, a lawyer, he pops down from the apartment he renovated for himself to an identical one below. His younger brother, Micael, claimed the penthouse. Gabriel is the middle brother in space as well as time.

Born in Zurich, he bounced around boarding schools in England, Canada, and Spain before going to Columbia. He is fluent in Spanish, English, German, French, Italian, and Swedish, but his parents insisted that each of the siblings choose a “difficult” language, too. Micael picked Arabic. Rafael chose Russian. Gabriel opted for Mandarin, which meant summers in China. (So did Sofia, the youngest, who is off to Columbia this fall.)

His contributions to the global Calatrava brand have been limited—“Dad designs all his projects,” he says. Still, rather than doing what most young designers do, drawing door handles and shopping for hinges, Gabriel started working as his father’s assistant, making travel arrangements and using his linguistic skills to schmooze with clients all over the world. “Right away,” he says, “I got exposure to the beginnings of projects, which is normally the part you learn about last.” When Santiago won the commission to design the Museu do Amanhã (Museum of Tomorrow) in Rio de Janeiro, Gabriel spent weeks interviewing plutocrats, physicists, psychologists, sidewalk vendors, schoolchildren, and homeless men, trying to distill a sense of what tomorrow meant to them. (These conversations took place in Portuguese, which he doesn’t even count as one of his languages.)

When the family bought the third townhouse, it was a wreck. He and his younger brother took on the renovation, an experience that invigorated Gabriel. (Micael later went into finance.) Each floor consisted of a long space running from the street to a back window, dodging the concrete shaft containing stairs, elevator, and plumbing. Rather than erect Sheetrock partitions, the Calatravas wanted to tie together the apartment’s different components with a single elegant gesture. The solution was to package the bathroom, kitchen, closets, and office in a big wooden box that allowed each area to be closed off. A set of folding panels slips out of a hallway compartment, like playing cards flying from a dealer’s fingers, hiding the kitchen and its mess. To choreograph that movement, the brothers bent standard aluminum rails into special tracks. A bookshelf swings silently shut, concealing the office. All the prosaic necessities—ducts, wires, light switches—vanish behind the skin of bleached oak.

Achieving simplicity is never simple. The construction materials couldn’t easily be hauled up the stairs, so Gabriel designed the apparatus in three-foot modules that could be brought through the windows. To ensure a uniform finish on the veneer, he bought an entire tree and had millworkers peel it like an orange. The darker-hued base supplied the first-floor unit, and the upper segments went into the higher floors, so that if you were to cut the building open, you would see an exploded oak growing up through a Park Avenue townhouse. To his surprise, Gabriel couldn’t find an American firm to deliver the refined woodwork he demanded at a reasonable price, so he gave the job to an outfit in Austria. Two carpenters came to New York and assembled each apartment in just seven days. The result of all this streamlining is the architectural equivalent of an Apple box, where every foam niche and cardboard flap contains a little gift—a gizmo, an accessory, a cable. You could spend a pleasant hour just sliding panels back and forth, listening to the latches click satisfyingly into place.

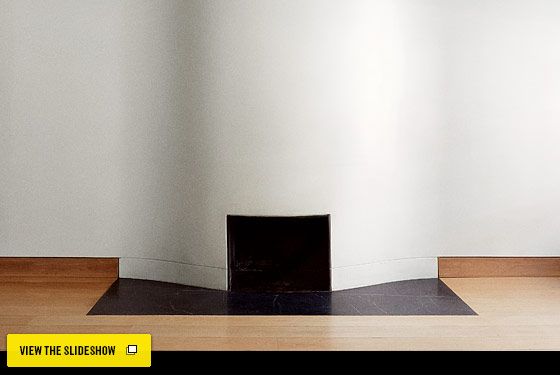

The Fireplace

The white wall bulges woozily, and the negative space appears to throw a shiny black shadow on the floor.

Photo: Thomas Loof

Three Brothers, Three Floors

Each virtually identical apartment contains a curved fireplace and a wood-paneled

cube housing an office, bathroom, and kitchen. Note that all three sons have a table designed by their father.

Third Floor:

Micael

Photo: Thomas Loof

Second Floor:

Gabriel

Photo: Thomas Loof

First Floor:

Rafael

Photo: Thomas Loof

The Cube: Open

With many hinges, drawers, flaps, and doors, it’s a kind of house within the apartments.

The Office

In the unlikely event of clutter, the whole office disappears.

The Kitchen

Appliances line up along the hallway with shipboard efficiency.

Photo: Thomas Loof

The Cube: Closed

The Oak Veneer

A single tree supplies the wood for all three apartments.

The Bedroom

The cube continues through the frosted-glass door into the sleeping area, where it turns into a set of closets.

Photo: Thomas Loof

The Kitchen

Panels slide like trolleys along curving rails, stowing away in their siding or forming a seamless wall.

Photo: Thomas Loof

The Kitchen Photo: Thomas Loof