Photographs by Iwan Baan

Caracas slides into the valley from the ring of slum-covered slopes where half its population of more than 3 million lives. At the low-lying center of the business district, a hulking skeleton in a battered glass mantle thrusts into the skyline. This is the Centro Financiero Confinanzas, conceived in 1990 as a gleaming hub for Venezuela’s financial class, who would one day vault over the street-level misery and land on the rooftop helipad, 600 feet in the air. It didn’t work out that way. David Brillembourg, the investor who gave the skyscraper its nickname, Torre de David, died in 1993. The following year, Venezuela’s banks collapsed, leaving the half-built skyscraper standing as an accidental monument to financial disaster.

The complex stood vacant until 2007, when a group of families led by the convict turned preacher Alexander Daza staged an orderly move-in and founded an instant vertical community. Residents policed themselves, assigned the elderly and disabled to the lower floors, and formed a cooperative to collect dues and manage the space. Today, about 625 families inhabit 28 of the tower’s 45 stories, trudging up unfinished staircases and hoping children stay away from empty elevator shafts and balconies that lack walls. Despite the dangers, the building provides a relatively safe haven in a city where, according to the U.S. State Department, travelers risk being kidnapped as soon as theyleave the airport.

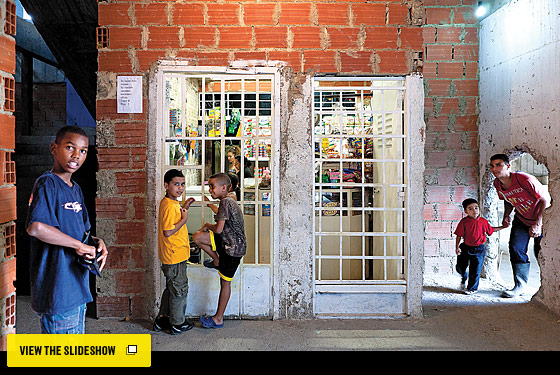

“It doesn’t look good, but it has the seed of a very interesting dream ofhow to organize life,” says Alfredo Brillembourg, an architect and relativeof the man who launched the construction. A co-founder of the firm Urban–Think Tank, Brillembourg sees the settlement as a font of lessons on how to adapt broken cities to the millions who flock to them. The tower’s residents managed to obtain electricity legally and rig up toilets to a rudimentary plumbing system. Motorbikes ply the parking structure’s spiral ramps, ferrying supplies up to a distribution center on the tenth floor. Urban Sherpas carry goods from there, hauling them up to tiny bodegas, where prices rise with altitude. Some residents have gradually marked off their quarters with finished walls.

“Compared to housing in many other neighborhoods, we have a pretty good quality of life,” says Gladys Flores, the secretary of the residents’ cooperative. “But we still need elevators.”

For all its improvisatory resourcefulness, the settlement represents a massive failure of civic society. After all, the government could choose at any time to make the building habitable and safe. Meanwhile, the skyscraper is a modern ruin buzzing with life, a postapocalyptic mockery of an oil-rich nation’s aspirations.

Photo: Iwan Baan