It’s college graduation season — a time of year for reflection and deep thought about life’s challenges, the ephemeral nature of youth, and the number of economics majors coming out of Ivy League schools.

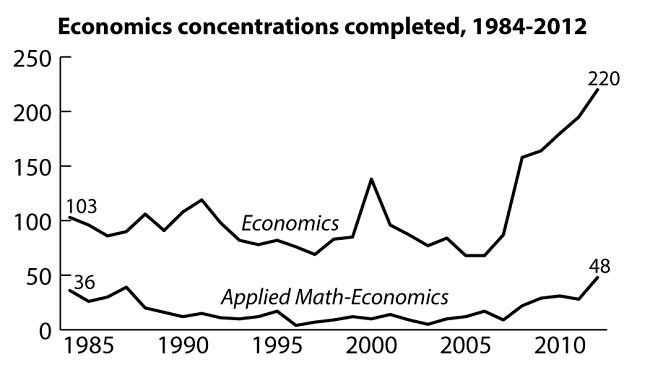

This year, as in most years, a plurality of the graduates of our nation’s top-ranked schools will have degrees in economics. The so-called “dismal science” has been one of the most popular majors at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton for many consecutive years, and students for decades have treated economics departments as a step toward jobs on Wall Street and in consulting. In recent years, the lust for econ degrees has spread to even those Ivies that are not known for producing budding young financiers. Even at Brown — yes, Brown, the grades-optional lefty paradise — 17 percent of this year’s graduating seniors had some kind of economics concentration under their belts. Brown is a bit miffed: President Christina Paxson has said too many economics concentrators see it as a Wall Street stepping-stone, and the school’s economics department has spoken about how the wave of interest has strained its resources, as the following Brown Daily Herald graph demonstrates:

I was intrigued by the curious case of the Brown economics bubble and decided to pull data from several other Ivy League schools, showing the popularity of the economics major over time.

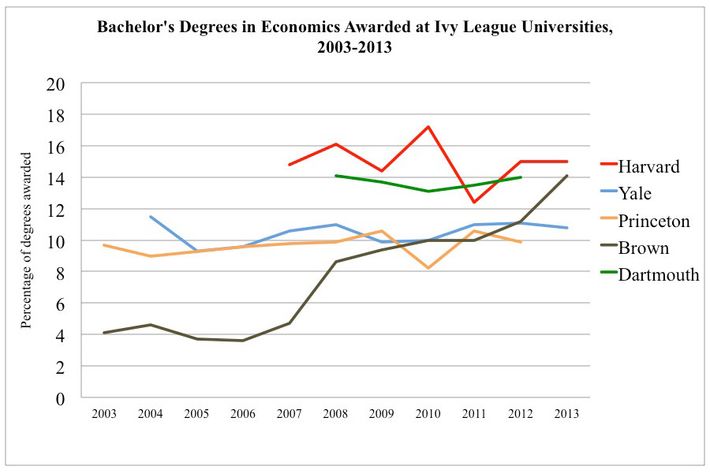

Before I get to the graph: a note on methodology. Lots of schools make selected major-by-major data available through their Offices of Institutional Research. Harvard’s data were provided both by its OIR and, for estimated figures for the last two years, by Professor Jeffrey Miron, who leads the undergraduate studies program at Harvard’s economics department. Data from Yale, Princeton, and Dartmouth were provided by those schools’ respective OIRs, and Brown’s data came from both its OIR and its economics department’s undergraduate studies director, Louis Putterman. I omitted Penn and Cornell because those schools have undergraduate business programs that mess up the numbers, and Columbia because it didn’t have previous years’ statistics posted in a place I could find. Wherever possible, I included just the pure economics majors and not majors of affiliated programs like applied math. And wherever possible, I calculated the economics majors as a percentage of all completed majors, not as a percentage of graduating students, to account for the possibility of double-majors. Also, Brown calls its majors “concentrations,” but it means the same thing.

Here’s what I found. You’ll note that while Brown is the biggest gainer — jumping from 4.1 percent economics concentrators in 2003 to around 14 percent this year (with an additional 3 percent choosing applied math–econ and mathematical economics) — the numbers have held relatively steadily at several other schools for the last few years.

In my mind, there are three plausible explanations for the rise in economics majors at Brown and the steady streams everywhere else. Let’s examine each one:

1. They’re all going to Wall Street.

Most Ivy League schools don’t offer finance or business degrees, so students hoping to land on Wall Street after graduation have often hoped to get the closest thing possible to a preprofessional education by majoring in econ.

But with the decline of the financial sector and the concurrent decline in recruiting on top college campuses since the crash of 2008, it’s not clear that economics majors from the Ivy League are actually flocking to financial firms like they once did.

In fact, at many schools, the number of econ majors is staying stable, while the number of students headed to Wall Street is falling precipitously. In 2006, before the crisis, 46 percent of Princeton students went directly into finance; last year, that number dipped to 11.5 percent. At Harvard, 15 percent of this year’s graduating class is planning to go into finance — roughly the same number that majored in economics. At other schools, the number of econ majors has eclipsed the number of Wall Street–bound seniors, a sign that not all of the growth in the econ major can be attributed to the financial sector’s siren song.

2. They’re being practical in a tough job market.

The job market is rarely “tough” for Ivy League graduates — they usually land on their feet somewhere — but the past few years have certainly been stressful for job-seeking overachievers. In the fact of such uncertainty, it’s natural that Ivy League students would seek a degree that is seen as a financial safety net. Economics majors earn more, on average, than majors in most other fields and have lower unemployment rates than graduates of other social sciences and humanities programs. And you can imagine how pushy parents, seeing the youth unemployment rate hovering above 15 percent, would prod their kids away from art history and philosophy and toward something that will make them more employable.

Perhaps Brown’s rising interest in economics means that it’s simply catching up to its rivals where pragmatic degree-searching is concerned. One Brown student summarized her reason for studying econ in an interview with the campus paper earlier this year: “Coming to college and shelling out a quarter of a million dollars, you want to make sure you can get a job.”

3. They’re — gasp! — actually interested in economics.

Another theory is that the financial crisis of 2008, and subsequent recession, have made it an exciting time to study what’s going on in the global economy. In other words, economics is hot right now. Professor Putterman at Brown shot this theory down: “Our casual impression is that the main motivator of student interest is still to get business, consulting, and finance type jobs,” he wrote me. “Students are under the belief that the strategy makes sense.”

But I don’t think it can be dismissed so easily. After all, this year’s seniors have been in college during an incredible period in our nation’s economy. Most of them matriculated in 2009, a truly dark year when the Dow was below 10,000 and the country was shedding hundreds of thousands of jobs a month in the midst of a global financial collapse. Understanding the basics of economic theory wasn’t just a good professional move — it was what allowed people to understand and contribute to the biggest stories of the day. And faced with the opportunity to study a field promising such immediate relevance, it would have made sense for some students to pick economics — where all the action was — over more arcane majors.

If the Great Recession is, in fact, responsible for the flood of new economics majors at Brown — either because it made students interested in the economy or because it scared them away from less practical majors — you’d expect to see a shift in the other direction in the next few years. Barring a double-dip recession, today’s freshmen and sophomores will have gone through college in very different economic times. And in a recovering economy, with fewer dramatic headlines about bank failures and billion-dollar bailouts, some of them might lose interest in economics or feel more confident about their chances of landing a job with a softer major.

But if Brown and other Ivies keep churning out econ majors, even in a strengthened economy with a depressed financial sector, it may mean something more lasting than a temporary, recession-fueled spike. It may mean that economics is the major of the future.