The debt-ceiling showdowns of 2011 and last spring both resolved themselves without triggering an economic meltdown, and so most people have come to assume the same will happen again this fall. I have been sounding the tocsins of doom for months. One cause for my alarm is that the Republican Party has grown even more rabid. Just as it responded to John McCain’s 2008 loss by moving right, it responded to Mitt Romney’s 2012 loss by moving right again. Republicans in Washington have completely abandoned any thought of pursuing their goals through compromise or other normal political channels, instead redoubling their tactic of extracting concessions by fomenting crises. Incredibly, in the face of a reelected Obama and a plunging deficit, the GOP’s demands for raising the debt ceiling are now more extravagant than the ones it issued in 2011.

There’s a second reason why a debt default crisis has grown far more likely: President Obama cannot negotiate the debt ceiling this time.

This reality is starting to dawn on the Republicans only very slowly. Republican leaders have spent the last few months trying to avoid a different, and far less severe, crisis, a government shutdown, by promising their members to hold the debt ceiling hostage. They shared the complacent, this-time-won’t-be-different conventional wisdom that has permeated Washington. It is slowly beginning to dawn on them that Obama may not submit this time around.

David Drucker reports that House Republicans are “intent on forcing President Obama to the negotiating table” over the debt ceiling. Republican senator Orrin Hatch writes a Wall Street Journal op-ed today imploring Obama to fork over a ransom to lift the debt ceiling:

Making his point melodramatically on Sunday, President Obama said, “We will not negotiate over whether or not America should keep its word and meet its obligations.”

In reality, Congress and administrations have for decades—under both Republican and Democratic presidents—negotiated over or included spending and budget reforms as a part of debt-ceiling increases.

Hatch presents his case as if he is rebutting Obama. He’s not. It is true that Congress has on occasion negotiated over budget changes “as part of debt-ceiling increases.” What does that mean? It means that when Congress makes a change in budget policy, it often appends a debt-ceiling increase to that. It does not mean that Congress has negotiated over whether to increase the debt ceiling.

Since Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, Congress has lifted the debt ceiling 45 times. Only a handful of those debt-ceiling hikes included any changes to budget policy. The historic rule has always been that, when the debt ceiling needs to be raised, Congress raises it without extracting concessions in return. If the two parties happen to be negotiating budget policy, they do it on a separate track and append the debt-ceiling increase to the final vote.

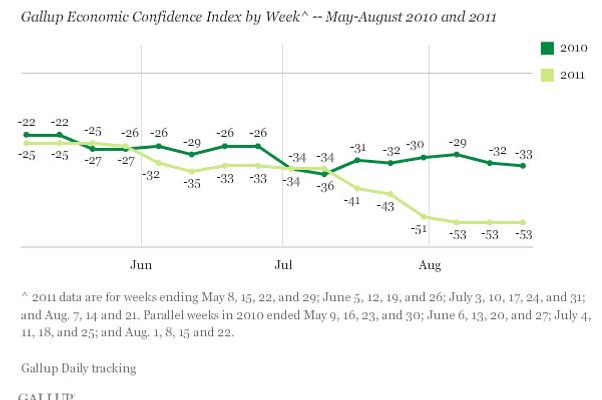

Of course, 2011 represents a break from the pattern. That is the one time Congress actually used the debt ceiling as a bargaining chip. From the Republican point of view, it was a satisfying experience, resulting in a trillion and a half dollars’ worth of spending cuts. The threat of default cost the government almost $19 billion directly in the form of higher interest payments, and cost the economy far more by shaking confidence:

And that was without default. Annie Lowery reports that a debt-ceiling breach could have potentially massive effects on the world economy — hundreds of billions of dollars, and possibly worse.

Republicans see the magnitude of a debt-ceiling breach as a reason to believe Obama will eventually negotiate. It’s actually a reason to believe he won’t.

The meta-conflict over whether the debt ceiling ought to be held hostage, or simply raised, has implications that extend well beyond the actual demands at hand. If Obama agrees to trade policy concessions for a debt-ceiling hike, he will permanently enshrine debt-ceiling hostage dramas in the practical functioning of American government. That means not only will unscrupulous opposition parties be able to wring concessions from himself and future presidents, but eventually a negotiating snag will trigger a real default.

This is what Obama meant when he said that enshrining the debt-ceiling hostage drama would alter “the constitutional structure of this government.” It would fundamentally change the country’s governing norms, permanently placing new and destructive power in the hands of Congress.

What’s more, Obama has placed his credibility on the line publicly by insisting he will not negotiate the debt ceiling. By doing so, he has essentially blocked off his own escape route. Folding would destroy his negotiating credibility in general and specifically make it impossible for him to stop a future debt-ceiling ransom. Not only are the Republicans’ absurdly grandiose debt-ceiling demands unacceptable — they’re currently calling for Obama to essentially accede to the entire Republican fiscal and regulatory agenda in addition to destroying his health-care law — but any demands are unacceptable.

The incentive structure for Obama is therefore such that a debt-ceiling breach, while terrible, is better than trading something to prevent one. But it’s not clear if Republicans actually don’t understand Obama’s incentive structure or are merely pretending not to understand it. Terrible though it may be, a default may actually be necessary to preserve the constitutional structure of American government and the rest of Obama’s presidency.