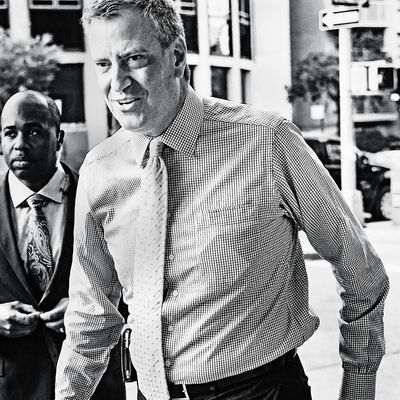

The world was a beautiful place as Bill de Blasio folded himself into the front passenger seat of a black SUV. The late-afternoon sun was shining on Park Slope, and a grand political breakthrough was within reach. Sure, it had been a complicated few weeks as Governor Andrew Cuomo and the Working Families Party, bitter codependents, tried to agree on a deal that would give Cuomo the WFP’s ballot line this fall in exchange for the governor’s publicly pledging to get behind a progressive policy agenda. Now, though, thanks in part to de Blasio’s mediation, a compromise was falling into place. He left Brooklyn for the drive north to bless the grudging bargain at the WFP’s convention in Albany.

Then the calls starting coming in to the mayor’s car. The WFP’s true believers were livid—they didn’t trust Cuomo to deliver a Democratic-majority State Senate. The party’s union backers were threatening to walk out and support the governor. The WFP activists were yelling, determined to reject Cuomo and nominate a professor with a name out of a Tom Robbins novel, Zephyr Teachout. It was as if some kind of bizarre principle of political particle physics had kicked in: The nearer de Blasio got to Albany, the more chaotic state politics became.

It got stranger when the mayor finally arrived at the convention site, a hotel whose interior is decorated to resemble a colonial village. Cuomo, at home in Westchester, shot a video to be played for the WFP. He looked miserable. The party’s activists were furious that the governor had deviated from the script they’d painstakingly negotiated. De Blasio and a top political aide, Emma Wolfe, a former WFP strategist, were crucial intermediaries. A solution was improvised: Cuomo would talk to the convention by speakerphone and pledge his allegiance more precisely.

When the shouting was finally over, after midnight, Cuomo had the nomination and the WFP had some concessions that have the potential to shake up New York politics for decades. Yet as de Blasio headed down the Thruway toward home, all the eccentric parochial skirmishing in Albany was merely a prelude to his dream of a far more ambitious convention, two years from now, back in Brooklyn.

De Blasio, after six months in office, has managed to shift the political polarity of the city and the state. So why stop there? The mayor has always aspired to lead not just a city but a progressive movement, and de Blasio’s bid to bring the 2016 Democratic National Convention to New York is a signal of his ambitions.

“The climate of the middle class, the destruction of people’s earning power, the inequality crisis, the crisis of income disparity, all of this is registered so deeply it’s like a radio signal that’s being sent out from all parts of the country that somehow doesn’t reach Washington, D.C.,” de Blasio said in a group interview with Salon, The Nation, and MSNBC. Liberal activists are cheering him on. “Bill de Blasio and Elizabeth Warren are the leading edge of this new wave that can transform the Democrats,” says MoveOn.org executive director Ilya Sheyman. “Income inequality will be to the 2016 Democratic primary what the war in Iraq was to the 2008 primary.”

De Blasio’s allies in the WFP are eager to become a national force. The party has had success beyond New York—helping elect school-board members in Bridgeport and Hartford, persuading the Oregon legislature to pass a student-debt-reduction plan. But it has been mostly a bicoastal player.

Last June, the longtime head of the WFP’s New York operation, Dan Cantor, became the party’s national director, and he is trying to replicate the local formula of uniting labor unions and liberal activists and expand beyond the WFP’s current seven chapters.

“That’s the idea,” says Bill Lipton, who was promoted to Cantor’s spot as director of WFP New York. “We believe there’s too much corporate influence in the Democratic Party, and that’s not good for the party or America. We see this as a really significant strategy to pressure the Democrats to either be more attentive to the grassroots and fight more for working families—or they can go the way of the Whig Party.”

And what better vehicle than to have one of the WFP’s founders, now the mayor of New York City, bring the 2016 Democratic National Convention to Brooklyn, the capital of urban-hipster progressivism? Especially when the Democrats’ expected nominee has her own issues with the left wing.

It all still sounds like wishful thinking, though. De Blasio is as much realist as lefty idealist. Brooklyn is not exactly the front-runner for the convention, and Hillary Clinton is not Andrew Cuomo. But they share an instinctual preference for the pragmatic political center and a coziness with big-money interests—traits that produce a common tension with the increasingly leftish Democratic Party base. “I assume she will not have a primary challenger,” a Team Hillary veteran says. “In 2008, Barack Obama was a superior political talent. And there is nobody like that out there right now. But Hillary will certainly have to deal with the fact that the party has moved significantly to the left.”

Clinton has already started. Worsening income inequality, she said in a recent speech, risks causing “social collapse.” But she could also use help from the man she demoted as her 2000 U.S. Senate campaign manager, de Blasio. That’s one reason Clinton showed up onstage at de Blasio’s inaugural—and appealing to the labor union and activist left is central to the city’s pitch for the 2016 DNC.

“During the Obama years, the theory was ‘Go to swing states and try to win independents,’ so the conventions were in Denver and Charlotte,” a Democratic operative says. “But the other strategy is ‘Go get the big-city base riled up,’ so that was New York in ’92, Chicago in ’96, Los Angeles in 2000. And that was the Clinton model.”

In launching the city’s bid, de Blasio highlighted New York’s “progressive spirit” as a potential energy source for the national party. Which was nifty marketing, at least for the de Blasio brand. But if New York lands the convention over Columbus, Phoenix, and the other contenders, merely holding the festivities at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush wouldn’t qualify as a progressive triumph (the symbolism would also be mixed: Barclays Center, the proposed convention headquarters, was supposed to be accompanied by affordable housing on the Atlantic Yards site). To become more than a tourist carnival, a Brooklyn DNC would need to confront the differences between mainstream Democrats and liberals over money and economic fairness. And the result would need to be more innovative than boosting spending for the Dems’ core constituencies.

Many of the WFP’s clashes with Cuomo have been fueled by the party’s desire to raise taxes on the wealthy. In 2011, when a state “millionaire’s tax” was due to expire, the party’s leaders nudged Occupy Wall Street to unfurl a banner at the state capitol reading GOVERNOR ONE PERCENT. Last month in Albany, the WFP got Cuomo to agree to five significant promises. But he drew the line at adding billions to the state’s already swollen education budget, which likely would have required a hefty tax increase.

Bill de Blasio has so far been successful inducing people like Andrew Cuomo to talk the progressive talk. Getting the national party, and Hillary Clinton, to walk the same line to the left will be harder, even if the path leads through Brooklyn.

*This article appears in the June 16, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.