From Barack Obama’s point of view, the arrival of the House Republican majority in 2011 has amounted to the greatest disaster of his presidency. It is, indeed, the wellspring of nearly everything that has gone wrong. The Republican majority has spurned all entreaties to compromise, turned routine operations of government into hostage dramas, ginned up pseudo-scandals, imposed senselessly punitive fiscal policies, and turned the capital’s political atmosphere into a wasteland, dragging the president’s approval ratings down with the GOP’s.

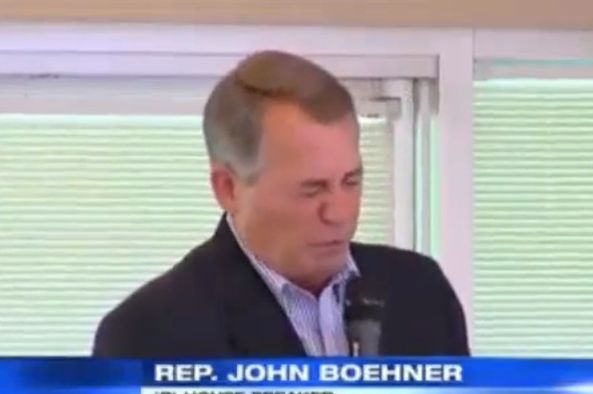

But from Hillary Clinton’s point of view, the picture looks quite different. In ways that have not yet fully manifested themselves, the dysfunctionality of the House has oddly redounded to her benefit. If Obama is succeeded by a fellow Democrat in 2017, she may have John Boehner — or, more precise, the unruly mobs of backbenchers making Boehner’s life hell — to thank. The Republicans’ immigration disaster has commanded most of the attention in this department. But it’s entirely possible the party’s fiscal policy will backfire just as badly.

The central idea animating the Republican hordes from the outset of their control of the House was a paralyzing fear of debt. As Paul Ryan warned in 2012, the United States faced “a debt crisis like Europe” within the next couple of years. This terror justified some of the most reckless confrontations — Republicans insisted they needed a “forcing mechanism” to save the country from the imminent danger of becoming Greece.

Even as deficits have settled back to normal levels, and hyperinflation, raging mobs, and other real or imagined Euro-catastrophes failed to materialize, Republicans remain wedded to their regimen of fiscal contraction. They have carried out deep cuts to domestic spending and have blocked badly needed infrastructure spending. Public-sector employment has fallen by 700,000 since Obama took office, after having increased by more than a million under each of the five previous presidents. Rather than stimulating economic growth through short-term deficit spending, Republicans have instead kept a fiscal vise that, according to macroeconomic forecasters, has held the recovery to a painfully slow rate of growth.

The fiscal vise has kept the jobless from obtaining work, kept those who do have work from bargaining for higher wages, and, incidentally, depressed Obama’s approval rating. This last fact has prompted mutterings among liberals that the GOP was engaged in political-economic sabotage — either willfully, or through the kind of self-deception that allows people to justify their self-interest.

But at the same time, the fiscal vise has had the likely side effect of extending the duration of the recovery. The workings of the macroeconomic business cycle are mysterious and defy any easy consensus. In general, however, the faster an economy reaches its peak capacity, the more likely it is to overheat. When businesses are humming and unemployment is low, it is easier for either inflation to accelerate or for bubbles to form (like the tech bubble of the 1990s, or the housing bubble of the 2000s). Inflation can provoke the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates, bringing the recovery to an end; popped bubble can cause a systemic crash. In this sense, the economy is like a car: When it’s zooming along, it’s hard to control.

The expansion has already exceeded the average length of a postwar economic recovery, and unemployment has not yet returned to normal levels. Last week, JP Morgan chief economist Michael Feroli published a short paper demonstrating that the speed of economic expansion since World War II has correlated inversely with its length. “Somewhat counter-intuitively,” he concluded, “the shortcomings of this expansion — an initially high unemployment rate and slow growth — are virtues when thinking about how much longer the expansion will run.”

To switch metaphors, now think of the recovery as a buffet dinner at a family restaurant. The food may be lousy, but at least there’s plenty of it. As the maitre d’ of this buffet, Hillary Clinton is likely to face an electorate of satiated (if not overjoyed) customers. Feroli projects “unemployment will not achieve its natural rate until the middle of next year, which would put the peak risk of a recession about four years on the horizon.” That would put the recovery on schedule to expire in 2018, just in time to position Republicans to benefit from another angry midterm wave, but not fast enough to win the White House.

Obviously, economies don’t always follow schedules. But the possibility of having manufactured the perfect economic conditions for their 2016 opponent must exasperate more cool-headed Republicans, who have spent the summer observing the near-certain backfiring of their party’s immigration policy.

There is no way to map out the course of the two years between now and the home stretch of the presidential election. Perhaps the Republican nominee will find some way to detach himself from the House’s nativist death grip; perhaps the recovery will unexpectedly perish. In the meantime, it is dawning on some observers that Obama’s pain may be Clinton’s gain.