The Republican Party has not always been the party of crazed reactionaries, or even the party of smaller government. Heather Cox Richardson, author of a forthcoming history of the party I’m eager to read, argues in the New York Times today that the GOP can once again reclaim its identity as the moderate, non-anti-government party of Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Eisenhower. “They would do better to look to earlier presidents,” she writes, “and model their new brand on the eras when the Republican Party opposed the control of government by an elite in favor of broader economic opportunity.”

I would very much like this to happen, but I don’t think it will, for one basic reason: the South.

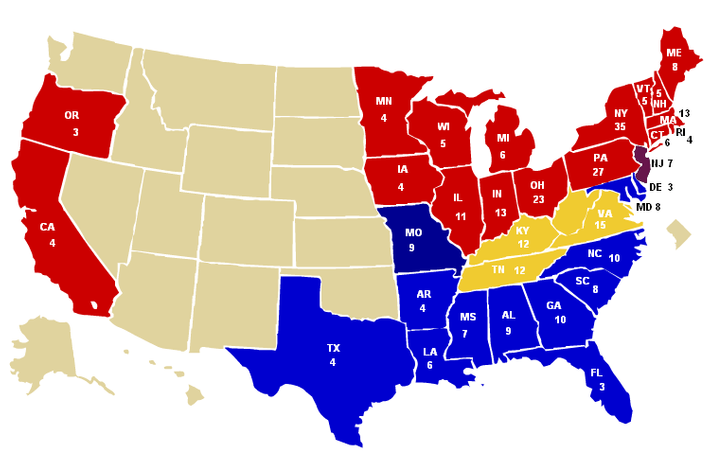

Richardson points to a trio of historic Republican presidents who favored activist government, or at least (as in Eisenhower’s case) were fundamentally comfortable with it. Here is Abraham Lincoln’s coalition in 1860:

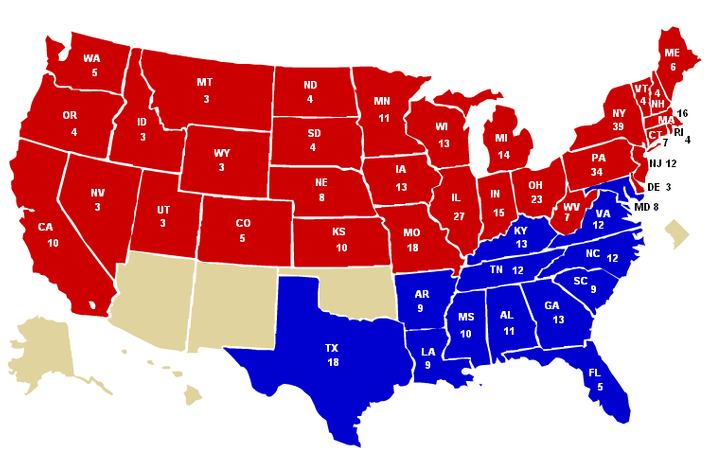

Here is Theodore Roosevelt’s coalition in 1904:

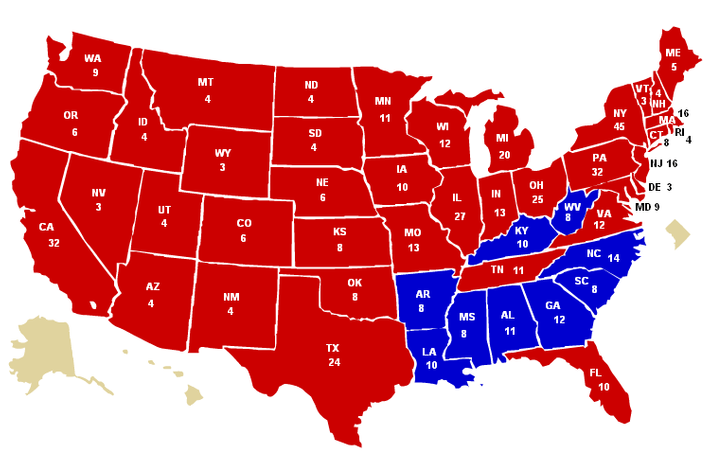

And here is Dwight Eisenhower’s in 1952:

The basic North-South split you see in all these maps is the historic natural division of American politics. One coalition is Greater New England —the areas of the United States settled originally, or in successive waves, by Yankees, with its greatest strength in the Northeast, and stretching through the upper Midwest and including California. The other coalition is based in the South, often including the Mountain West, with its greatest strength in the Deep South.

The broad ideological contours of those coalitions have held firm for some two centuries. Southerners, dating back to Andrew Jackson, strongly opposed a centralized government, believed the Constitution strictly prevented the government from intervening in the economy, distrusted cultural change, and represented the interests of whites as opposed to nonwhites. (Jackson’s defenses of strict Constitutionalism and the gold standard, and hatred for the national bank, perfectly anticipate tea-party economics.) Northerners believed more or less the opposite.

The interesting thing, from today’s perspective, is that the party alignment is the opposite of the contemporary one — today Democrats represent the northern coalition, with their most intense support in New England, and Republicans the Southern coalition, with their most intense support in the Deep South.

In between the 19th century North-South alignment and the contemporary version, the party system got scrambled for a while. During the first half of the 20th century, the Democratic Party split between a liberal northern faction and a conservative southern one. That split opened enormous tensions within the Democratic Party, which grew increasingly hard to paper over — first manifesting itself as a problem of Congressional coalition management for Franklin Roosevelt, then as a third-party presidential defection in 1948, and finally as a total collapse when the conservative movement took control of the Republican Party starting in 1964, leading to a process where the South aligned itself wholesale with the GOP.

We’re unlikely to return to a mid-20th century situation where the white South is going to support the more liberal party in presidential politics. American politics has instead returned to what appears, historically, to be its natural state. Given that the alliance between the white South and the Republican Party has grown more firm than ever, it is hard to imagine how the party can refashion itself along Lincolnian or Rooseveltian lines.