Facebook is releasing a new stand-alone app today, the latest in a string of hit-or-miss efforts from its Facebook Creative Labs division. The app, which was created by a team led by Branch founder Josh Miller over the last six months, is called Rooms, and it allows users to create semi-private spaces where they discuss and share content on topics of their choice — sports teams, bands, obscure hobbies, and the like.

As was widely expected, Rooms is a departure from Facebook’s real-names-only policy. Users can be pseudonymous (no Facebook login is required, only an email address), the rooms they create can be invite-only, and while the moderation tools allow room-starters to police their own turfs, the idea is to let people use rooms in whatever ways they choose — to discuss the latest woodworking techniques, gossip about Beyoncé and Jay, or sound off on the World Series, either with strangers or with groups they handpick themselves.

In the demo I got from Miller last week, the app appeared to be an intuitive, well-designed way to create groups for topic-specific conversation, using an innovative invite system (basically, taking phone screenshots of QR codes — I promise, it’s not as awkward as it sounds) to bring newcomers in. Miller walked me through a sample group called “Butterflies,” a place for butterfly enthusiasts to share their views. The Room itself looks a lot like an Instagram or Vine feed. The entire process from deciding on the group’s name to inviting other users took about a minute, and I was able to customize things like the shape and name of the “like” button on posts within the group.

To anyone born before, say, 1991, Rooms will feel familiar. Essentially, it’s a retro reboot of Metafilter, Usenet, IRC, and other Web 1.0 platforms where people congregated to discuss their interests. It’s the first Facebook-designed app that looks backward in internet time — to the web we used to have, before Snapchat and Twitter and Facebook itself changed the ways we communicated. And it’s an attempt, I think, to bring some of the self-policing instincts of those early communities to bear in the new world of anonymous apps, with all the bad actors those apps tend to enable.

That’s not an accident. Miller says he consulted with the proprietors of those Web 1.0 communities while building Rooms, people like Metafilter’s Matt Haughey, in an attempt to capture some of the atavistic intrigue of those early sounding boards while keeping the space safe from trolls and harassers.

“What are some of the things from the early days of the World Wide Web that we should put on a phone?” Miller says he thought.

Rooms isn’t the only project hoping to recapture some of the magic of the early web. Ello, a stripped-down, ad-free social network that launched earlier this year, billed itself as being committed to the ideals of “beauty, simplicity, and transparency.” The site, which just announced a $5.5 million funding round this morning, looks like 1991 — unlike Rooms, which merely acts like it — with old-school typefaces, an ad-free, desktop-only layout, and a simple feature set that lacks staples like photo sharing.

“The whole social network experience has become sort of a drag, for a lot of different reasons, one of them clearly being advertising,” Ello founder Paul Budnitz told Inc. earlier this month. “But when you take away the ads, and the data mining, you are free to just do really good design.”

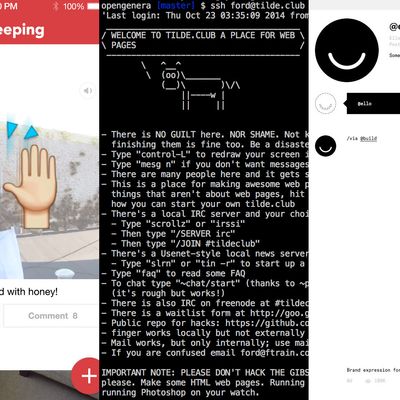

Ello isn’t the apotheosis of old-web nostalgia. That would be Tilde.club, another invitation-only social network run by engineer (and New York contributor) Paul Ford. Ford describes Tilde.club as “one cheap Linux computer on the internet with a funny name and nothing else added.” Go to the site’s pages, and you’ll see all the artifacts of the Usenet-era web — spinning GIFs, horrendous frame layouts, links to actual “webrings” consisting of other member pages. Ford doesn’t make any money from the site — in fact, as he explained in a Medium post about it, there is no business model for Tilde.club, only the desire to create a simple, stable sandbox for other old-web aficionados to play around in. There are currently 7,000 people on the waiting list, Ford says.

“I think the people who joined miss the freedom of the early web and wanted a chance to reboot and do stuff that is ugly or weird and celebrate that a little,” he told me. “Some people see it as retro goofiness, some people see it as the first node of a potential social network, some see it as a lark, some see it a kind of snobbish conspiracy. It’s sort of a mirror of their own internet anxieties.”

It’s also possible to see Rooms, Ello, and Tilde.club as a rebuke of the new internet _ a place dominated by designed-by-committee apps that raise millions before the first users even sign up, where interactions are either real and largely mundane (Facebook, Instagram, most of Twitter), or shadowy and toxic (Yik Yak, Reddit, 4chan). These new experiments could be viewed as a set of divining rods, all trying to find the remaining lifeblood of the authentic, largely anonymous communities of enthusiasts and like-minded individuals that formed during the web’s early days.

Of course, the retro web wasn’t perfect — the first troll was born on a BBS somewhere — so the makers of these nostalgic communities have had to be thoughtful about how to keep the good parts of Web 1.0 while discarding the bad. For Facebook’s Miller, that meant implementing strong moderation features that allow users to control the boundaries of their own Rooms and approve posts by other members, coupled with 24/7 support from Facebook’s enormous team of moderators to ensure “zero tolerance” of bullying, hate speech, or explicit content.

Free-for-alls these aren’t. But what Rooms offers — and what Tilde.club and Ello also provide, in their own ways — is a kind of reset button for social identities, a way to free ourselves from the performance prisons we’ve built. Some of what they’re used for will likely be frivolous. (Miller used the example of high-end watch collectors talking amongst themselves in a Room — not necessarily a hobby you’d want to broadcast to all your Facebook friends.) But you can also imagine different, humbler kinds of people rediscovering the small thrill of meeting strangers with shared interests.

“If you add up all the online communities, it’s just as big, if not bigger, than Facebook,” Miller says.

Consolidating these communities, and preserving the result, will take effort. With apps and web services, the temptation is always to grow, broaden, and get less weird. Ford says he has no plans to make Tilde.club a mainstream service. (“Until I started this I had no idea how much I missed the unfiltered writing of people who are deeply into things … and I hope that by not putting too much pressure on this project it will stay that way for a while,” he says.) But Facebook doesn’t have the same restraint. It can’t. It’s a $200 billion company that needs advertising dollars _ and harvested user data — to thrive.

Right now, there are no ads on Rooms, and no ways for Facebook to access the kind of detailed user data it collects in its main app. It’s a skunkworks project, meant simply to test the public’s appetite for a throwback BBS-style app. But success could change the mandate. If it does, the app’s retro tendencies may start to feel a lot more modern, and the old web will grow smaller in the rear-view.