The American political debate has transformed radically over the last month. The underlying policy faultlines remain, but the tenor is unrecognizable. When the Republican majority took control of the House of Representatives in 2011, they had the crusading air of a party fired with the conviction that it had to save America from imminent destruction. It had the same millennial fanaticism in the fall of 2013, when Republicans shut down the government to protest Obamacare. The onset of the Republican Senate, by contrast, is accompanied not by tones of revolutionary fervor but torpor and confusion.

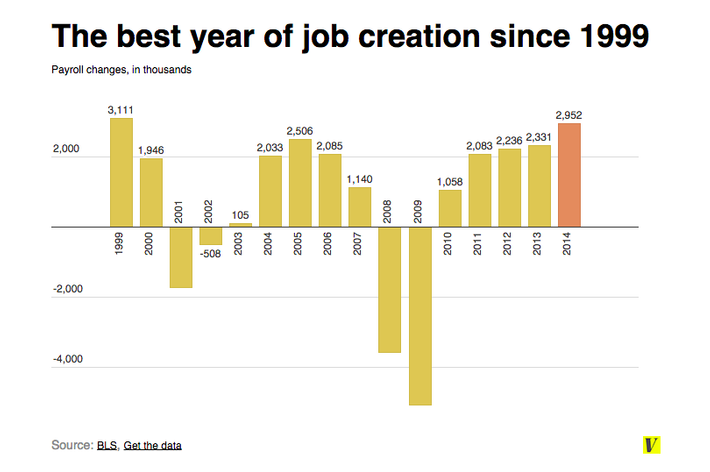

Before the holidays, it was possible and even probable to think of the American economy as disappointing. This is no longer plausible. Today’s jobs report confirms that the recovery has shifted into a more rapid phase of growth. 2014 saw the recovery finally escape its languid post-crash phase. More Americans gained jobs in 2014 than any year since 1999.

The recovery is not complete — wages remain stubbornly suppressed — but this fact itself suggests an upside: The absence of higher pay is also the absence of any kind of inflationary pressure that might cause the Federal Reserve to apply the brakes to the recovery. This in turn suggests job growth is not finished. The 2016 elections could well take place against a backdrop of full employment. The entire predicate of the Republican argument since 2009 — that Obama’s massive expansion of spending, taxes, and regulation has snuffed out job creators’ incentive or ability to work their capitalistic magic — will be moot.

In 1996, the recovery was still embryonic enough that Bob Dole could lamely assert that Americans were suffering from “the Clinton crunch.” Four years later, George W. Bush had to acknowledge widespread prosperity, while casting himself as the ideological heir to Clinton’s moderate policies and running on “honor and dignity.” That is the sort of reversal currently under way.

Mitch McConnell underscored the metamorphosis when he acknowledged the economic recovery with inadvertent humor. “The uptick,” insisted the incoming Senate Majority Leader, “appears to coincide with the biggest political change of the Obama administration’s long tenure in Washington: the expectation of a new Republican Congress.” Neither half of McConnell’s statement is true. First, the biggest political change of Obama’s tenure, by far, was the Republican capture of the House during his first midterm election, which destroyed the Democrats’ ability to pass new legislation. Republican bills will be blocked by Obama vetoes or by Senate Democratic minority filibusters rather than by the Senate Democratic majority. The addition of the Republican Senate does not change the state of gridlock between the two parties; any agreement between the Republican House and Obama would be amenable to a Republican or a Democratic Senate. Nor does the recovery in any way coincide with the relatively insignificant change in Senate majority. The Republican Senate victory was not expected until November. The accelerating recovery was evident as early as June (as this prescient Joe Wiesenthal column attests).

One can see the change, too, in the GOP’s early policy feints. As promised, the party is holding a vote to build the Keystone pipeline. Keystone was always a symbolic issue, but the symbolism was powerful because it gave Republicans a way to situate their policies as the answer to the electorate’s genuine concerns. Americans worried about a lack of jobs and high gasoline prices. The pipeline offered no substantive relief to either concern, but it could be sold as one. But with jobs growing briskly, and gasoline prices falling through the floor, Keystone’s symbolic value loses almost all its potency. If Republicans succeeded in authorizing the pipeline, it is not even clear that it would make enough economic sense to even build today. Keystone has been reduced to a vestigial gesture of resentment against environmentalists. They are doing it because they have already committed to doing so, not because it makes any contemporary sense.

Likewise, the party remains as committed as ever to repealing Obamacare, but its apocalyptic terror continues to subside as the law continues to function effectively. Republicans are holding a show vote to alter the employer mandate, and their proposal would increase the deficit while reducing the number of Americans with insurance. The gambit has divided the party, with National Review registering its opposition.

Signs of faint-heartedness in the anti-Obamacare jihad continue to pop up. Republicans in North Carolina and Texas have floated the possibility of ending their state’s boycott of Obamacare. Senator John Cornyn has suggested postponing the party’s annual vote to restore the pre-Obamacare status quo.

There is no evidence the Republican Party has changed its policy doctrine. (Indeed, if you consider the last predicate, in 2001, George W. Bush implemented the same tax cut agenda that Bob Dole advocated in 1996.) Yet if the lyrics remain the same, the music is radically different. Six years of unrelenting hysteria have given way to a world in which Republicans can no longer claim that Barack Obama has transformed the country beyond recognition. Their goal is no longer to assign blame but to seize a share of the credit.