A Nicholas Sparks novel always features a decent, loyal leading man who works hard and knows how to throw a punch. He has just one vulnerability: a high-spirited, oftentimes blonde woman. One look and love strikes. Not the complicated push-pull version: Romance is sudden, unconflicted, and, after that first kiss, unbreakable. There are barriers, of course — class differences, secret pasts — but “love isn’t always easy,” Sparks tells fans. “Fight for it.” In his novels, which have sold nearly 100 million copies, the lovers always do.

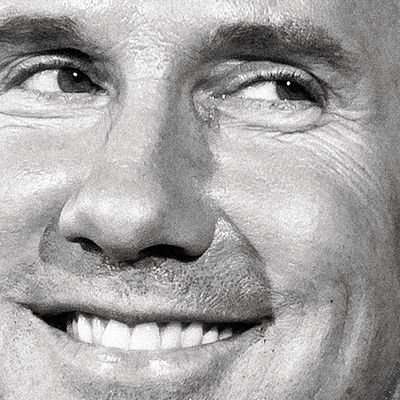

Critics dismiss the Sparksian universe as preposterous. But Sparks claims to live in it. Sparks, who has doe eyes and a wide, goofy smile, once pinned a thief to the ground with his bare hands. Like his characters, he fell hard when love struck. The second day he saw his wife, Cathy, he declared he was going to marry her.

Sparks writes his stories with Hollywood in mind — he has on occasion written the screenplay before the novel — and nine of his books have been turned into films, collectively grossing almost $1 billion. The tenth, The Longest Ride, is due this spring, and this time his tale of mismatched lovers comes with a twist. Sparks’s leading men have been ethnically indistinguishable: white Christians who look good without a shirt. A narrator of The Longest Ride is Ira Levinson, a 91-year-old who is the author’s first Jewish character. Sparks, a devout Catholic, says that Levinson is based on his grandmother’s partner, whom he refers to as his surrogate grandfather.

That’s not the only departure from Sparks’s tried-and-true narrative. The Sparksian persona, long his best creation, has lately faced plot twists of its own. For the first time in his career, the author has dealt with waves of bad publicity. Last year, Sparks split with his wife — poof! There goes happily-ever-after. And just as the warm, wise, fictional Levinson made his appearance, a real Jew, a former employee, filed a lawsuit accusing Sparks of religious discrimination as well as racism and homophobia.

Nicholas Sparks was a 28-year-old pharmaceuticals salesman living in New Bern, North Carolina, when he decided to take a stab at writing a romance novel. His choice was based mostly on his assessment of the financial possibilities. He’d researched the genre and calculated that there was room for his kind of love story. When he turned in his adaptation of the 60-year love affair of his wife’s grandparents — she has Alzheimer’s, and her husband regularly retells her the story of how they fell in love — Warner Books paid him $1 million for it, a huge sum that turned out to be a great investment. The Notebook became a New York Times best seller in 1996, and so did each of his next 17 books.

Sparks has often insisted that his books are more complicated than the run-of-the-mill romance novel. His oeuvre may not be taken seriously by serious people, but his stunning wealth is, and it has gained him entry into a realm important to him, that of serious issues and ideas. In 2011, he funded the Nicholas Sparks Foundation to help disadvantaged kids. He endowed three fellowships at his alma mater, Notre Dame. And it was in 2006 that he launched his most ambitious project, the Epiphany School, a Christian-oriented prep school in New Bern.

It was “a whim at first. Let’s make our own school,” Cathy told a Christian website. But Sparks doesn’t do anything halfheartedly. (When his preschool-age son, who suffers from a neurological condition, couldn’t talk, Sparks seat-belted him into a chair for six hours until he formed the word apple.) He poured $10 million into the campus and subsidized tuition.

Three years after its founding, Epiphany graduated its first class, every one of its students college-bound. Still, it was perceived as “a community where a fundamentalist minority spoke with a loud voice,” said Bill Hawkins, pastor of First Presbyterian in New Bern. Sparks is a faithful Christian but not a fire-breather, and he wanted students to study and participate in the world. Yet Epiphany was seen as a place to which conservative Christians sent their children for safekeeping, just what he’d hoped to move beyond. “His is outsized success in everything he’s done. Writing books and movies, he’s on top,” said Peter Relic, who worked with Sparks on governance issues at Epiphany in 2013. “His school was going to be recognized throughout the world.”

To do that, Sparks decided he needed a new headmaster. In late 2012, a headhunter suggested a distinguished educator named Saul Hillel Benjamin. They, like many Sparks pairings, were an odd couple. Benjamin was an intellectual snob, a slight, 64-year-old Jewish-born Quaker who’d gone to Kenyon and Oxford. He’d worked in Bill Clinton’s Department of Education and served as a professor at the historically black Bennett College. More recently he’d lectured at prep schools in cities from Stuttgart to Beirut. It wasn’t until late in life that he’d started his family; his first child arrived when he was past 60. Up to then, his spare time had been devoted to playing the violin and writing poetry.

When Sparks called him, Benjamin was teaching at Al Akhawayn, a university in Morocco modeled on the American system. “I’d gone to give a talk about teacher professional development, and it went too well,” Benjamin explained to me. Benjamin could be “super-patronizing,” a former colleague said, but he had a reputation as an inspiring teacher. At Al Akhawayn, Benjamin said, “I was creating a liberal-arts and cross-cultural interfaith undergraduate program. Doing my usual.”

On the phone, Benjamin informed Sparks that he hadn’t read any of his books. Sparks was gracious: “Don’t worry, enough people do.” Sparks knew just how to woo Benjamin; he told him that he’d changed the school’s name to Epiphany School of Global Studies to reflect his expanded ambitions. And then he asked Benjamin questions about curriculum development and teacher mentoring, topics he was an expert on.

Benjamin, according to a former colleague, had his own reasons to take Sparks’s interest seriously. There aren’t many headmaster jobs around. His appointment at Al Akhawayn could end at any time. Sparks offered a four-year contract, a secondary job at his foundation, and a salary of more than $250,000 for the two positions — a lot of money in academe. One colleague urged him to pass on the job; the partnership was too far-fetched. But, Benjamin told himself, it offered the kind of opportunity an idealistic educator — someone “faithful to learning,” as he put it — would jump at. “He’s a dreamer,” said a friend.

Sparks bought a fancy house to accommodate the new headmaster and, while it was being renovated, put the Benjamins up at his own compound. There, the relationship deepened. Benjamin cooked for him; the two took drives in Sparks’s “extraordinarily gorgeous black Bentley,” as Benjamin described it, and shared confidences by the infinity pool. They talked about increasing diversity at the school, which had only two black students among 514 enrollees. Sparks informed Benjamin that he wanted to implement “academic/curricular improvements,” a goal Benjamin endorsed. Benjamin wanted to expand educational vistas and Epiphany’s tiny library. Sparks agreed wholeheartedly. “They seemed to have one shared vision,” said one person who watched them at a seminar.

Sparks warned that the path to change would be bumpy. Three or four of the trustees believed the Earth was flat, he joked. But Sparks assured him that Benjamin and he were in this together. “It was pretty remarkable how close we were,” Benjamin later said.

In the first weeks of the 2013–14 school year, Benjamin moved aggressively to implement changes he thought they’d agreed on. At Benjamin’s urging, the trustees adopted a nondiscrimination policy that mentioned sexual orientation. He courted black leaders, shuttling students to Washington, D.C., for the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s march on the Capitol. During one town-hall meeting, he talked about the shared heritage of Jews, Muslims, and Christians. Benjamin understood that his views were unsettling to some — “How dare you talk about Islam,” one parent informed him — but he viewed himself as an Enlightenment warrior engaged in an epic battle. “I’m going to work with these people. I can help them see the light,” he told a friend.

Sparks cautioned Benjamin that he was moving too fast. “You have to first win their hearts,” he wrote in emails. “Some [people] perceive … an agenda that strives to make homosexuality open and accepted … The [board] will not sanction a club or association for GLBT students,” he wrote, confusing the shorthand LGBT, and neither would he. Perhaps Sparks was more socially conservative than he’d let on, perhaps more than he’d realized himself. “As for the club, there obviously can’t be one now.” (Sparks declined to be interviewed for this story.)

As Thanksgiving approached, Sparks grew “both angry and frustrated,” according to lengthy emails he was sending to Benjamin. Conservative trustees were in revolt, and Sparks complained that he had to put out “raging infernos.” Benjamin rubbed people the wrong way, he added.

Privately, Sparks was offended too. It was one thing to sit by an infinity pool and gossip about narrow-minded Bible literalists. It was another to talk as if the school were broken, which is the message Sparks drew from Benjamin’s comments. Why did Benjamin spend so much time haranguing people about “tolerance, diversity, non-discrimination,” instead of mentoring teachers and developing a curriculum? “There was no simmering, hidden problem,” Sparks insisted to Benjamin. “It is, and has been since its founding, a kind school, where everyone is kind.”

On November 16, 2013, Sparks’s wife paid a surprise visit to Benjamin’s home. She was accompanied by a trustee who had a pointed question for Benjamin: Do you believe in God?

“Yes,” he answered, though he felt compelled to add, “but it’s an answer that takes some explaining.”

A few weeks ago, in the office of his New York attorney, Douglas Wigdor, Benjamin faced me across a round table. He wore a corduroy sport coat, tie, and casual gray pants, looking like a liberal-arts teacher off to a seminar. On the subject of his last days at Epiphany he was direct and emotional.

On November 19, roughly three months after the semester started, Benjamin said, he was summoned to explain his beliefs before a community assembly. “I’ve never experienced so much vitriol about my heritage or my faith in people’s ability to learn,” he said, referring to the event as a “public lynching.” Two days later, Benjamin said in his complaint, he was virtually held hostage by Sparks and two Epiphany board members in a school conference room. In Benjamin’s recollection, Sparks was a towering, enraged presence who stalked the room, blocking the door and screaming: “You bastard. You liar.”

Sparks likes to be in control of a situation — at one point he wanted to ban protests at the school — and he’d started to find Benjamin disruptive. Perhaps Benjamin did, at times, make himself a central character in a drama in which there were other important players, a former colleague said. Sparks, though, had a more dramatic interpretation. He suggested that the educator whose intellect had so impressed him might be suffering from Alzheimer’s, like the character in The Notebook. (Benjamin isn’t, his lawyer says.) At the meeting, Benjamin wrote out a resignation letter on yellow lined paper, which he says was dictated by Ken Gray, a trustee and attorney. (Gray didn’t return phone calls.) “It was the most frightening moment of my life,” Benjamin told me. “[I was] weeping, broken, humiliated. I’m ashamed that I allowed that to happen.” He signed.

This past fall, Benjamin fought back, filing a lawsuit that claimed Epiphany had violated his contract. He also claimed in his complaint that the school was “a veritable cauldron of bigotry.” He would later say, “I saw real ugliness.” Bullying was all too common as well, he said.

Sparks briefly returned fire through the press. His longtime entertainment lawyer and friend Scott Schwimer — who is gay and Jewish — told journalists that he found the allegations against Sparks absurd. Sparks briefly explained the breakup of his marriage. His readers were crestfallen: “How am I supposed to believe in love anymore when Nicholas Sparks is getting a divorce?” bemoaned one on Twitter.

And then Sparks, who is rarely off-message, tried to put the Benjamin debacle behind him. He hired a new headmaster for Epiphany — this time the school advertised for a “solid Christian educator.” He returned to work — he writes a book a year — and started to think about The Longest Ride. Sparks, who has been his own best salesman, had to hope that the new film would help woo back confused fans. The movie features his customary love story. “We come from such different worlds,” says Sophia, a blonde art student played by Britt Robertson, about a hunky bull rider named Luke, played by Scott Eastwood. In a bit of luck for Sparks, the film is narrated by Levinson, a sympathetic old Jew played by Alan Alda. Levinson encourages Sophia to fight for love. She follows his advice and asks Luke to be patient. Appearances aren’t everything. In the book, she tells him, “People rarely understand that nothing is ever exactly what you think it will be.”

*This article appears in the February 9, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.