Why Do Severed Goat Heads Keep Turning Up in Brooklyn?

<span>Some say it’s a strange religious ritual. Others, a prank. I went on a quest to find the answer.</span>

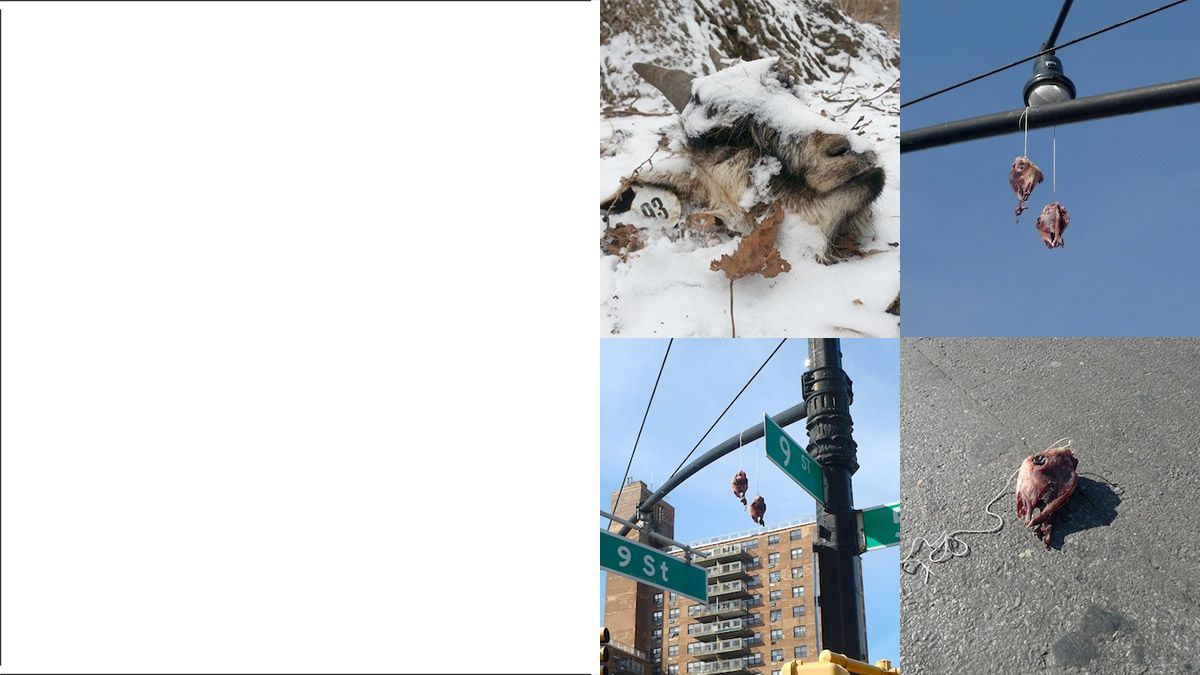

At the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Ninth Street in Brooklyn, the heart of Park Slope’s tree-lined prosperity abruptly gives way to grittier windswept blocks that march south to Sunset Park and west to the Gowanus Canal. Trucks and cars speed down Ninth Street as dusty construction workers, sharply dressed professionals, nannies with strollers, and roughhousing teens hustle across Fifth Avenue, all on their way to somewhere else. Perhaps this neither-here-nor-there-ness explains why two skinned goat heads that appeared without explanation above the intersection last November remained there for days. The heads were tied together at the base of the skull with twine and slung over a light pole on the intersection’s northeast corner. After at least four days, an employee from a nearby car service knocked the goat heads down with a pole and threw them in a garbage can.

Or maybe the sluggish reaction to the Park Slope goat heads signals the extent to which such discoveries have become a routine occurrence in the area. Severed goat heads keep turning up in nearby Prospect Park. Last year alone, readers sent the blog Gothamist photographic evidence of three goat heads found in the park. (In all of these cases, the goat heads had their skin still attached.) Gothamist seems to be experiencing something like goat-head fatigue, judging from the increasingly nonchalant tone of its goat-head coverage. Pretty soon it will probably take a cow head to get them excited. "It's New York,” one spectacularly unimpressed passerby told DNAinfo. “I've seen the towers come down, so beyond that, nothing really stings that bad.”

But while repeated exposure to goat heads may have inured some local residents, others have sensed an unsettling trend. Many news reports about the Park Slope goat heads suggested a dark link to the goat heads discovered in Prospect Park. “Residents have questioned whether the incidents could be connected to religious animal sacrifice,” The Wall Street Journal wrote. The specter of Santería was invoked. The Drudge Report picked up the story. The goat heads went global. As I read all this in my apartment a few blocks from the site of the hanging goat heads, I was riveted. A mysterious flood of goat heads is the only interesting thing that has happened in Park Slope since I moved to the neighborhood three years ago. Yes, the rush to blame a little-understood religion practiced largely by immigrants smacked a bit of lazy xenophobia, but the idea of Park Slope as a hotbed of animal sacrifice, in addition to child-friendly bars, was undeniably intriguing. In a city where everyday occurrences are casually weighed against the events of September 11, 2001, it was shocking to find that so many of my neighbors and I were actually shocked. The goat heads seemed to rear out of some shadow New York City that was even gnarlier than the pre-Guiliani version I’d seen in the movies, and at the edge of Brooklyn’s most thoroughly gentrified neighborhood, to boot. When New York asked me to investigate the goat heads, I leapt at the chance. I wanted to see if the world they hinted at lived up to the hype.

I quickly learned that any answers would not be forthcoming from official channels. The NYPD opened an investigation into the hanging goat heads back in November, but a public information officer with Park Slope’s 78th Precinct informed me that “no further information has been found out.” A spokesman for the Prospect Park Alliance said, “I don't think anyone in the park is going to have that much to say about it.” A FOIL request I filed with the New York City Parks and Recreation Department (for “all records related to reports of decapitated animal corpses and animal heads found in New York City parks between the years 2010–2014”) didn’t seem to be at the top of their list of priorities.

It was time to consult the oracle. I Googled “Goat heads + New York.” Here I learned that the city’s suburbs have been experiencing an oddly complementary goat-head related issue. Last fall in Westchester County, a bunch of headless goat carcasses began to turn up in public places. When a decapitated goat was found in a plastic bag along with some chicken carcasses in September, the authorities there leaped into action and called upon an occult expert named Marcos Quinones to investigate. Maybe he’d have some insight into the Goat Heads of Park Slope, I thought. But I mentioned Quinones to Alex Mar, a journalist who has researched the occult and fringe religions in America for her upcoming book Witches of America, and she wrote back: “Watch out for those 'occult experts.' Very 80s-paranoia.” Indeed, Quinones has been helping law enforcement investigate possible ritualistic sacrifices since the 1980s, when the U.S. was seized by a nationwide panic over Satanism and the occult, sparked by now-debunked reports of satanic ritual abuse in preschools. But surely the field of occult investigation has evolved since then, right?

I called Quinones and told him I had a case for him. I described the hanging goat heads of Park Slope, and the other goat heads found in Prospect Park. “I think I can help,” he said. “Are you just focusing on goat heads?”

“Yes, I’m focusing on goat heads specifically,” I said.

“Basically it’s one of three things,” Quinones said. “It’s Santería, or Vodou, or Palo Mayombe.” Santería, Vodou, and Palo Mayombe are the three most prominent Afro-Caribbean religions. All three descend from African religions, brought to the Caribbean by slaves who preserved them, often in secret, despite slave-owners’ best, brutal attempts to Christianize them. Santería and Palo Mayombe originated on the sugarcane plantations of Cuba, while Vodou developed in Haiti. All three religions are practiced in the U.S. by immigrants who have large communities in Brooklyn, and contain a component of ritual animal sacrifice. Quinones’s conclusion made intuitive sense, but then I considered the journalist’s warning to me: Wasn’t it self-serving for an expert in the occult to see animal sacrifices wherever he looked? I wanted more proof. I asked Quinones how he would start looking into the goat heads himself.

“What I would recommend you to do is look on the internet for botanicas,” he said. Botanicas are small religious-goods stores that dot New York City. With cluttered window displays and signs lettered in fading, hand-drawn script, many botanicas might be mistaken for a thrift store or a garden-supply shop. They sell oils, candles, statues, herbs, soaps, and other curios — all the equipment one might need for spiritual pursuits ranging from Santería to various New Age religions to your garden-variety Catholicism. Like any businessperson, the botanica owner must be attuned to the local market; if goat sacrifice was getting hot in the Park Slope area, a nearby botanica owner might know why.

“Give them a call and talk to them,” Quinones said. “Keep in mind they're very, very secretive.” But not so secretive that they aren’t on Yelp, it turned out. Within five minutes I’d found a botanica in Park Slope (4.5 stars) not so far from where the goat heads had appeared, and just blocks from my apartment. I must have passed it dozens of times without noticing it. Quinones, who lives in Manhattan, agreed to accompany me, and we met at a coffee shop in my neighborhood to plot our moves.

Marcos Quinones, in person, looks more like a gym teacher than a paranoia-monger. He’s a short, round man with a neatly trimmed mustache and a full head of sweeping grey hair, who was dressed in a black sweatshirt and windbreaker pants. Quinones sipped on an orange San Pellegrino as he expounded, in a mellifluous Nuyorican accent, on the potential meaning of goat heads. Animal sacrifices, he said, are often discovered in parks near significant populations of Afro-Caribbean and Latino immigrants. Santería is a nature-oriented religion, so offerings to the gods, known as orishas, are sometimes required to be left outdoors, near rivers or oceans (or maybe a Superfund-site canal).

But, he continued, there could be other, more sinister meanings. “It could be a death ritual,” Quinones said, his tone growing darker. “For example, across the country and in New York State, you might have a cow’s tongue nailed to a tree, and that’s a ritual to shut someone up.” Inside the tongues, he added, would be pieces of paper with names of people the supplicant wished to silence. Sometimes the pieces of paper will have the names of witnesses in a criminal trial.

There was also the possibility that the goat heads meant nothing at all. Quinones was more equivocal on this point than he’d been on the phone. “It could just be a bunch of kids playing around, you never know,” he said.

Most of what Quinones told me about Santería squared with what I would read in books later. Although he’s an Evangelical Christian and an ordained minister who has even performed an exorcism or two, his uncle is a well-known high priest of Santería in Puerto Rico, and Quinones can sometimes seem sympathetic to the non-Christian religions he investigates.

As we entered the botanica, Quinones and I were greeted cheerfully by a woman behind the register wearing what appeared to be purple hospital scrubs. “I’ll be with you in just a second!” she called as we squeezed past a woman in a North Face jacket who was purchasing $60 worth of herbs and soap plus a spiritual reading. It felt like Quinones and I had stumbled into the living room of an excessively spiritual hoarder. We examined a wall made up of dozens of small square bottles of oil with names like “Court Case Oil,” “Keep Away Hate Oil,” and “Bat’s Blood Oil.”

When the customer was done, we approached the register. “We’re working on a story about Santería, and were wondering if we could talk to you,” Quinones said. The cashier’s friendliness vanished. “You’re going to have to talk to the owner. He’s not here. I don’t know when he’ll be back.” She produced a rubber stamp and stamped a small scrap of paper, then handed me a makeshift business card with his number.

Despite our failure, Quinones assured me that the world of Santería was becoming more open in general. In the occult-frenzied 1980s, the NYPD had raided Santería practitioners, and some were fined for animal abuse. But in 1994, a landmark Supreme Court case ruled that humane animal sacrifice was protected under the First Amendment. “Even though the stigma’s there, it’s not as bad as it used to be,” Quinones said. “Freedom of information, the internet. You can look up botanicas on the internet and have hundred of listings!” But we had no more success at the second botanica than the first. The owner crossed his arms at the entrance and firmly refused Marcos’s request for an interview.

“I think he sensed something and just felt that he shouldn’t speak with us,” Quinones said enigmatically as we drove back to Park Slope. Cue Twilight Zone music. When I first enlisted his help I had imagined Quinones would help me wield the tools of Rational Inquiry to cut through the supernatural haze. Now I understood that he is a skeptic, but not in the sense that he doesn’t believe in the power of Santería or the occult: He just thinks it’s the wrong way to go about things.

Meanwhile, there was the mystery of the goat heads’ provenance. Where do you buy a goat head in New York City? In November, police sources speculated that the Park Slope heads had been procured from a nearby halal meat market. The closest of these to the intersection of Fifth and Ninth is Al-Noor Halal Meat Market, on Fifth Avenue and 22nd Street. So a couple days after the ill-fated botanica visits, I took the bus there.

The red-and-white sign above Al-Noor reads “Lamb, Goat, Veal, Sheep & Chicken.” I pushed open a tinted-glass door and a concentrated barnyard funk charged up my nostrils. Live chickens lined the left-hand wall of the cavernous concrete room in cages stacked seven feet high, clucking and shuffling softly. A woman in a headscarf spoke to an attendant behind a Plexiglas window as two small children clung to her dress. At the back of the room, a doorway offered a glimpse into another room where an animal mass filled a pen. Could those be goats? An attendant directed me to the owner, sitting in a leather chair behind a glass door. He put a cell phone call on hold, with obvious irritation, and I stammered out that I wanted to know if the goat heads down on Ninth Street had come from his store.

“Those didn’t come from us,” he snapped in a way that suggested he’d been asked this before. “Why don’t you go ask the butchers around there? Why did you come all the way down here?”He said they didn’t even sell goats, despite the sign outside. I thought we were alone in the room, but just then a large bald man stuck his head out from behind the door I’d opened. “You want to find goats? Talk to Indians. Goat is the only meat they eat!” I apologized for the interruption and said I’d look for some Indians. I left the office, and headed through the doorway where I’d seen the four-legged animals.

They turned out to be lambs. The lambs were packed in the tiny pen so tightly, their dingy woolen backs formed a sort of living shag carpet. I asked the attendant standing back there if they ever sold any goats. “Sure,” he said. He pointed to a corner of the pen. I’d missed two small goats huddling there pathetically, in an apparent attempt to put as much space between them and the writhing lamb-mass as possible. He said they sell about six goats per week, “mostly to Mexican guys.” But they only sell whole goats, not heads, and they only sell them after they’ve been slaughtered. If any Santeros needed a live goat to sacrifice, they wouldn’t be getting them from Al-Noor.

I walked slowly back to Park Slope, becoming depressed as I thought about how, after two days spent attempting to ask the staffs of minority-owned businesses intrusive questions, I was still no closer to figuring out where the hell the goat heads had come from. At home, I remembered the stamped business card I’d got at that first botanica. I dialed the number, and the owner picked up. He agreed to meet under two conditions. “If you're writing about anything negative, I don't want to have anything to do with it,” he said. “And if you write anything contrary to what I believe, I will sue you.”

I got to the shop just before closing time. The owner was a big, middle-aged Latino man, wearing jeans and an American Eagle hoodie. His brusqueness on the phone had convinced me that as soon as I said the words “goat heads,” he would fly into a rage. Instead, he burst into laughter.

“Did you hear that?” he said to a woman restocking a shelf of candles at his feet. “Goat heads on a telephone pole!” The woman shook her head. The owner collected himself. He hadn’t heard of the goat-head incident before this, but he was sure it wasn’t Santería.

“That sounds like just some kids messing around,” he said. But it was getting late, and he had to get home to his family. If I wanted to hear the truth about Santería I would have to come back tomorrow, in the morning, before his day filled up with appointments for spiritual readings. As I left, he reiterated his warning about misrepresenting his beliefs, now tempered with a joke. “Remember what I told you,” he said with a laugh. “Or I’ll put voodoo on you!”

When I returned, the owner sat at a wooden table in a tiny back room, gluing dyed crow's feathers to a colorful hat that would be worn by one of his congregants in an upcoming drumming ceremony. Today he wore a different American Eagle sweatshirt. A metal pot full of herbs sat on a hot plate in the corner. He is, it turns out, a Santería priest who goes by the name Equi Lade. He has been a priest for decades, having first been introduced to the religion by one of Tito Puente’s dancers. I got the feeling that he wanted to speak to me to prove that Santeria has nothing to hide: Santería has become increasingly accepted in New York City, practiced not just by Cuban immigrants and Puerto Ricans like Equi Lade, but by Jews and Asians, celebrities and (unnamed) politicians. Many of Equi Lade’s customers in Park Slope are Russian immigrants — Russia, Equi Lade explained, developed a large Santería community thanks to the country’s Cold War alliance with Cuba. Santería is nondogmatic and flexible, coexisting easily with other religions on both a sociological and individual level. (Many Santería practitioners are also practicing Catholics.)

But Equi Lade is wary of the stigma that still surrounds Santería, especially the animal sacrifice part. Before we began our discussion, he made me promise that I wouldn’t name his botanica or use his legal name in my article. He didn’t want to have to deal with a parade of other clueless people like me who might assume that he knew something about the goat heads of Park Slope. “I don’t want someone from PETA coming around here,” he said.

And anyway, Equi Lade was adamant the goat heads were not the work of a legitimate Santería priest. “First of all, a priest wouldn’t throw up heads tied up like that. That’s really disrespectful.” Animal sacrifice is a sober ritual, practiced only by the highest order of Santería priest; the animals are slaughtered with humane precision and the body parts are handled with care. Goat heads appear repeatedly in literature about Santería, but there is no mention of leaving them in public places, much less so flamboyantly. Michael Atwood Mason’s Living Santería describes the initiation ceremony of a Santería priest, in which a goat is sacrificed and its head is placed next to sacred objects as an offering to the orishas. A mixture of “salt, palm oil, and honey” is placed on the base of the goat’s skull, and the initiate puts his tongue to the mixture to taste it. I asked Equi Lade what would be done with a head after a ceremony like this. He said you’d have to ask the orishas where the head should go, but “nine times out of ten, it goes into the garbage can.”

He admitted that Santería priests will sometimes leave sacrifices outside at intersections in New York City. These are offerings to the orisha Elegua, guardian of the crossroads, a powerful messenger god who oversees human communication with all other gods. But these sacrifices are typically low-key affairs — literally — low to the ground, so that Elegua can reach it.

“Let’s say you wanted to do a ritual for Elegua,” he said. “The most common thing you’d take would be like a gourd. The gourd may have toasted corn, may have honey, may have smoked fish. You might put that gourd in a bag and you’d put it on the corner. So the idea is that Eshu, the spirit that lives in the street, will take of that offering. But also the mice and the birds would eat it and it would be just the same as the deity eating it. You wouldn’t put it somewhere it wasn’t going to be accessible to a creature that would be able to take it. So that hanging there? That seems to me that someone’s just being very malicious. Or God knows what they were thinking.”

They may have been thinking of profit. Thanks in part to its lack of central authority and the secrecy that surrounds some of its practices, Santería is plagued by what Equi Lade describes as “shyster” priests just out to make a buck. The shyster priests might claim to have the power to extract a quick quid pro quo from the orishas, securing the client a new job or a girlfriend in exchange for a sacrifice (and a hefty fee). In recent years, Equi Lade has noticed an uptick of shysters. Many, he said, are recent immigrants capitalizing on their status as other. “You know, I hate to say this, but there are a lot of people who come from other countries, and people assume they know. They follow anything they say and it’s really wrong,” he said.

I showed him photos of each of the goat heads found in Prospect Park. In each case he ruled out Santería. In one case, the head was found near the body, which was gutted and stuffed in a trash bag. “That’s nasty,” Equi Lade said, grimacing. Another head was found garnished with what appeared to be a yellow flower on its forehead. “There wouldn’t be flowers like that,” Equi Lade said. Another rested on a plate laden with melted wax, corn, and other food items. “Maybe that’s Palo.” Despite the public association of Santería with animal sacrifice, Equi Lade said the practice is rare. “It’s a last resort,” he said. “You would do that in case someone is very sick and they were dying.” He has never sacrificed an animal himself in his many years as a priest. He knocked on the wooden table. “Thank God I’ve never had someone who was going to die!”

One thing that became clear in speaking with Equi Lade is that the skinned goat heads on the light pole in Park Slope and the whole goat heads found in Prospect Park are categorically different phenomena, and connecting them is a mistake. The only thing they have in common are that they are goat heads. The skinned heads, likely purchased from a butcher and hurled haphazardly where all could see, are opposed in every way to the practice of Santería, where fickle gods demand ritualistic perfection and harmony with nature is prized. Despite Equi Lade’s disavowal, some of the heads in Prospect Park, nestled in the bushes or placed beneath a tree, do indeed appear to have Santería connections. I showed a photo of one head snapped in Prospect Park last year by a photographer who posted it on Flickr to a Santería priest and software developer in California named Marcos Sanchez. It was covered in reddish-yellow wax and sat on a plate with kernels of corn and a chicken head. “These are definitely Santería-related,” he told me. He explained that the color most likely came from Epo, a kind of palm oil used in Santería sacrifice. But he said only a sloppy priest would leave heads lying out for dog walkers to discover. In the rare cases Sanchez is called to leave an animal sacrifice outdoors, say, in a park or on a beach, he will put it in the nearest trashcan so he doesn’t disturb others. “There's nothing that says you can't leave it in a garbage can,” he said.

Equi Lade had one other theory about the hanging goat heads: Vodou. Given how vociferously he’d defended his religion from accusations of goat-head-related littering, I was surprised when he suggested that another often-stigmatized Afro-Carribean religion might be to blame. But Equi Lade’s speculation was grounded in experience. He said he’d lived next to a Vodou priestess while growing up in Brooklyn. One day the priestess got in a fight with a neighbor. “The next day,” he said, “we woke up and there were two goat heads in a box on her doorstep.”

So, a few days after my meeting with Equi Lade, I met Jamais Bouque Bonmambo Domlage, a Vodou priest in Brooklyn. But she, too, shook her head when I showed her the photos of the Park Slope goat heads. “That is not Vodou,” she said. We were standing in the lobby of her apartment building in Flatbush; she had just come from her shift as a home medical aid and still wore her knee-length winter coat. She is used to Vodou being slandered and misunderstood. Vodou’s reputation is arguably even worse than Santería’s: in the popular imagination, voodoo dolls are used to bring harm to enemies and zombies. “Most people when they’re thinking of Vodou, they’re thinking it’s a bad thing,” Jamais said.

But Jamais’s Vodou is a religion of liberation and solidarity, the faith of the slaves in Haiti who revolted against the French and created the first black republic in the world. Jamais took out her smartphone and began to scroll through her Facebook account. Her Vodou house, Sosyetekle Erez, does much of its organizing on Facebook. Album after album showed Sosyetekle’s “parties”: women in brightly colored dresses, sweaty men beating drums in basements in the midst of ecstatic celebration. At a summertime ceremony for Egwe, the god of the sea, dozens of worshipers in all-white outfits and sky-blue bandannas drummed and danced beneath a white tent in a green meadow at Riis Beach. The altar to Egwe was cluttered with offerings of bottles of rum, crabs, and a cake adorned with a picture of St. Clare of Assisi. The ceremony couldn’t have been further from the sinister, grinning goat skulls. It looked like a wedding. “People celebrating, people dancing, that is us,” Jamais said. If someone had hung those skulls in name of Vodou, she said, it would have been “fake Vodou.”

Fake Vodou, fake Santería. The only thing I knew to be real about the Park Slope goat heads were the heads themselves, and I still hadn’t seen one of the damn things. The only other butcher shop near the site of the goat heads is a purveyor of gourmet meats called Fleischer’s — the kind of place where they’d tell you not only the name of the farmer who ethically raised the cow that became your expensive steak, but his zodiac sign too. And Fleischer’s had already told The Wall Street Journal that goat heads are “not really available.”

When I asked Equi Lade where he thought the heads came from, he surprised me by saying he thought they came from the halal market, Al-Noor. He knows the market well. His Jamaican friends make an aphrodisiac soup called cow cod soup from bull penises they buy there. He’d been there himself and seen goat heads for sale: He explained that next door to the building with the live animals was a small market run by the same owners. That’s where the heads were.

I went to the market. A long, old-fashioned meat case held chicken feet and bull penises, impressive racks of ribs, various unidentifiable organs, and, at the very end of the case, a single skinned animal head. “Is that a goat head?” I asked the butcher excitedly. He looked up from the frozen pig’s foot he was slicing with an enormous electric knife. No, he said, it was a lamb’s head. “We don’t sell goat heads.” I asked where I could find one. He said that butchers further south on Fifth Avenue, in Bay Ridge, sell them. I called a couple of them, but neither sold goat heads. One told me I could find them on Church Avenue, in Flatbush.

So I headed to Flatbush. My first stop was the Key Food on Church Avenue and East 42nd Street. I walked to the meat cooler in the back. On a shelf between frozen whole rabbits and chicken necks sat three goat heads. They cost $1.99 per pound and lay on a Styrofoam tray wrapped in cellophane like any other piece of meat. If you know where to look, obtaining the raw materials to start the next Great Goat Head Panic is as easy as buying a pork chop. I picked up a head and was surprised by its heft. If nothing else, the person who left the goat heads of Park Slope must have had a really strong arm.

On February 6, I finally got an email from the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation in response to my FOIL request for reports of decapitated animals in city parks. Attached to the email was a PDF, which turned out to be a full 64 pages long. There were 33 separate reports of animal heads and decapitated carcasses in parks from 2010–2014, ranging from chickens to cats, dogs, doves, pigeons, hawks, pigs, and, of course, goats. “I’VE SEEN AS MUCH AS SEVEN SQUIRRELS DEAD IN THE PARK,” went one report. “I’VE SEEN ONE THAT’S DECAPITATED.” Another: “THERE IS A DEAD ANIMALS HEAD ON A STICK ON THE GROUND.” It was impossible not to divine patterns as I skimmed through all-caps descriptions of carnage like the star of a gritty prestige-TV drama tracking a serial killer of urban wildlife. Chicken heads turn up on the west side of Manhattan in Inwood Hill Park and on the east side in Highbridge Park, while Central Park is utterly free of animal beheadings.

But most germane to my quest: The data indicate that Prospect Park has hosted an unusual number of decapitated goats over the past five years. Out of the 33 reports, nine were goat-related: seven goat heads and two decapitated goat carcasses. And out of those, half — three heads and one carcass — were discovered in Prospect Park. (Another report of an unidentified "large animal" with "whitish fur" discovered sans head in Prospect Park sounded to me like a goat, too.) Many of the reports include speculation that the goat heads related to religious rituals. But if any definitive conclusions have been reached, they are filed away in some other corner of the city's bureaucracy.

As I worked through the documents, I began to tweet screenshots of the most gruesome reports. If I could not definitively solve the mystery of the goat heads, at least I could entertain my Twitter followers. Soon I received an email from Stephen Brown, a courts reporter at the New York Daily News. Brown had seen my tweets and informed me that as a cub reporter working at the Brooklyn Paper in 2010, he had followed a remarkably similar story. It began with the discovery of bloodstained rocks, an unexplained fire, and smashed turtle shells on the lakeshore in Prospect Park. More and more animal remains came to light, and the Brooklyn Paper covered each with barely restrained glee and a grindhouse film director’s eye for stomach-turning detail in an entertaining series called “The Butcher of Prospect Park.”

Brown’s 2010 stories speculated on a connection to Santería, and I asked whether he’d ever solved the mystery definitively. “We never did figure out the identity or identities of the Butcher of Prospect Park,” he wrote. Experts told him that the crushed turtle shells weren't Santería, and a goat head discovered with wax was an "amateurish" sacrifice at best. I was struck by the similarity of Brown’s findings to mine. His ultimate conclusion, he said, was that many of the dead animals haunting New York City have less to do with marginal religions than with juvenile delinquency (maybe combined with the readily available — but inexpert — internet information about those marginal religions). “I tend to believe many of the dead creatures in the park at that time were the work of twisted teens pulling pranks, ” he wrote.

The mystery continues to grow. Just this week, a woman walking her dog found a gnarly severed goat head in a Prospect Heights park. Across the country, in Sacramento, there's been a similar decapitated-animal spree. The goat head’s goggle-eyed grin continues to intrigue amateur sleuths. But I couldn't get excited about this latest sighting. I'd followed the thread as far as I could, and it led to a bunch of normal-looking New Yorkers whose congregations fill rented basements on the weekends. It is a world defined by the demands of the spirits but also by city regulations, public relations, personal taste, and jostling communities. In other words, it is New York City. Everyone I spoke to had a different take on the goat heads of Park Slope, but no matter which god they prayed to, all agreed on one thing: Whoever put them there was a total jerk.