It’s been a bad year for polls. They were wrong in forecasting a close vote in the Greek referendum last month, wrong in overstating the Labour Party’s strength in the British elections in May, off in predicting the outcomes in the Israeli election, and off in the Scottish independence referendum last September. “The world may have a polling problem,” Nate Silver, the ur-analyst of polling, declared in his postmortem of what went wrong with the U.K. polls in May. “Polls, in the U.K. and in other places around the world, appear to be getting worse as it becomes more challenging to contact a representative sample of voters,” he said in another post. The crisis is not merely relegated to faraway lands: The polls were off in forecasting the size of the GOP wave in the 2014 midterms, too.

This is troubling news for the staffers, candidates, consultants, and partisans who — even if they try to deny it — have become more obsessed with polls in recent the last two election cycles than ever before. No one has forgotten the shock Mitt Romney and his pollster Neil Newhouse received in 2012 when they realized the internal forecasts predicting a Romney win were dead wrong. It would be one thing if Newhouse’s miscalculation was the only example they could point to; if they could write off the 2012 blunder as a cautionary tale of an in-the-tank partisan cooking up misbegotten math — after all, the track record from American pollsters in general election polls is still pretty good — but the recent examples across the pond are evidence that even the unaffiliated are capable of getting it very, very wrong. It’s a question the most competitive campaign hacks should lose sleep over: Which numbers can they trust? “As we get ready for 2016, everyone should be suspicious of every poll,” says Jay Leve, the founder and former newspaper man who runs the polling giant Survey USA. “There are really no polls that automatically qualify as beyond scrutiny.”

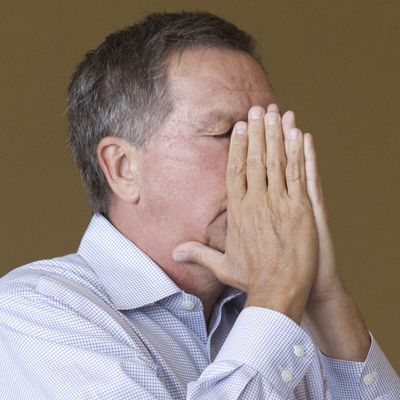

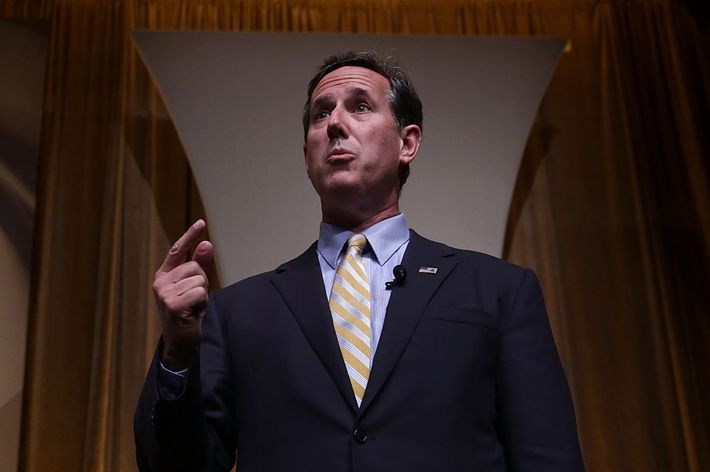

The great 2016 election freak out over the polls has already begun. Even while the honest pollsters are acknowledging that it’s getting harder to do their job well, the networks hosting the first two GOP debates — Fox and CNN — have decided to make national polling averages determine who gets the top ten slots for the primary debates. Getting on that first debate stage Thursday, in front of a prime-time audience with nine other GOP contenders, is a hugely important test of legitimacy. Those who don’t make it are as good as dogmeat — unless they can win enough hearts and minds in Iowa and New Hampshire to claw their way back into the race. Right now, the polling averages appear to exclude the only woman running in the GOP primary (Carly Fiorina), the guy who proved Mitt Romney’s most viable challenger last time around (Rick Santorum), an experienced senator (Lindsey Graham), and at least two governors — including, quite possibly, the chief executive of the state where the first debate is being held (John Kasich) — all in the name of a deeply flawed formula. “I think it sucks,” Graham blurted, when asked what he thought of the criteria on MSNBC last week.

There is no one who hates the criteria more than pollsters themselves. “It’s a pretty terrible process,” says Tom Jensen, who runs the liberal outlet Public Policy Polling. “It’s trying to create a level of precision in figuring out the top ten candidates that really doesn’t exist. Right now the difference between getting in the debate is the difference between 2 and 2.4 percent in an averaging of the polls. If a poll has about 500 respondents, the difference between 2 and 2.4 is the difference between 10 and 12 people supporting you. You’re saying two respondents to the poll will give you the chance to break out in this field or not, and that’s just wrong.”

There are good reasons pollsters want to distance themselves from the debate picking process. Using the national primary polls to try to figure out who’s in tenth, eleventh, and twelfth place, when all of those candidates are averaging within the margin of error of one another, seems especially absurd. If Christie, Perry, and Bobby Jindal averaging 3.2 percent, 2.2 percent, and 1.4 percent in the national primary polls respectively, as the Real Clear Politics averages indicate, does this tell us something meaningful? Or does it give too much authority to an industry struggling to get the big picture right?

Leve thinks the latter. The profession he’s worked in for more than two decades is being upended by the fact that it still relies on automated dialing services meant for use on home telephones, even though home lines have quickly become an antiquated technology. “When I started polling over 20 years ago, people were fretting that response rates were only 50 percent or so,” says Patrick Murray, who runs Monmouth Polling. “Now they’re down to about 10.” For a long time, lower response rates weren’t such a big deal, because the people who answered land lines were older, whiter, and more likely to turn out to vote than the general population.

But in recent presidential election cycles, the voting population has gotten younger and more diverse. The old model of just auto-dialing home phones doesn’t cut it it anymore. In theory, those cell phone-only voters should be easy to reach — almost all of them have cell phones — but cell phones are protected by law from the kind of automatic dialing systems favored by pollsters. Even those who are able to reach cell-phone users still have to figure out how much weight they should be given in a poll. “That introduces a lot more art into the process than in an ideal world, where it’s supposed to be scientific,” Jensen says. The industry has begun moving towards more online polling, but it still feels behind the times. “The only people who don’t think it’s a crisis are the apologists for the status quo,” Leve says. “And too many of my colleagues and brethren come across to me as apologists for the status quo. They want to deny that the world has materially changed since 1980. Nobody wants to answer a telephone. I don’t answer the phone if it’s my own mother calling.”

So what’s a campaign to do about the debate criteria? Some candidates and the PACS backing them are throwing millions of dollars into campaign ads to give themselves an artificial bump in the national primary polls ahead of the debates. Others are grasping for media attention. A few are sucking it up and trying to focus on fundamentals. “The day Senator Santorum won the 2012 Iowa Caucus, he was polling at 4 percent nationally,” says Matt Beynon, Santorum’s spokesman. “National polls mean nothing, particularly at this early stage. What matters is what type of organization you are building in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina. That’s our focus, not national cable buys now to try and get a couple extra points in a national poll.”

For their sake, the pollsters are really hoping the anger over the debate criteria doesn’t erode even more trust in their profession — or worse, get them lumped in with those loathsome political journalists. “The polls and the media are not that popular as institutions right now,” says Lee Miringoff, who runs Marist polling. He’s chuckling as he says it, but there’s an unmistakable touch of ruefulness in his voice. “To make them guardians of who gets in the debate seems like not a good use of these vehicles.”