So: It looks like the Rand Paul operation has popped a cotter pin (or several, really), and, as is generally the case when these things happen, the nuts spilled out. The man who was once hailed as a maverick party unifier is now regarded as a disappointment, a failure, toast.

But this meltdown was inevitable.

Eight years ago, I wrote a story for this magazine about the types of personalities best suited to the relentless, wall-to-wall grind of the campaign trail. Along the way, I reread Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life, a classic in sociology I’d remembered loving as a college undergraduate. If read a certain way, the book doubles as a manual in political communication, explaining how we “perform” our way through the world. The most useful point Goffman makes is deceptively simple: All of us have a front-stage personality and a backstage one. Our front-stage personality is the person the public sees, the person we are in front of our bosses, at cocktail parties, at parent-teacher conferences. The backstage personality is the person our dearest friends and family sees, the private person we are when strangers aren’t around to judge.

In politics, sometimes there’s too great a distance between someone’s front-stage and backstage personalities for comfort. We can tell that although he or she may be saying one thing onstage, he or she privately believes another. (Mitt Romney and his small varmint gun come to mind here. No, really. I love hunting! Love love love it! Guns are my favorite!) We can sense the cynicism. This person inevitably comes across as fake.

But here’s the thing: Other people in politics — in life, actually — have almost no front-stage personalities to speak of. They may modify their personalities a teeny tiny bit when they’re out in public, but essentially, they’re backstage characters all the time. They are not particularly comfortable performing. They are raw. Often angry. And often ironic, observing the political process with a certain amusing meta-detachment.

Every campaign cycle, the media becomes infatuated with a candidate with a backstage personality. They’re catnip to us, because they bullshit less than the typical pol. We call them “authentic.” Thank God for them, piercing the fourth wall, saying what they think. John McCain was like this for a while, particularly in the 2000 primary, when he walked around humming the theme song from Star Wars. (The name of his bus? The Straight Talk Express.) Howard Dean was like this in 2004. (Remember his uncensored yelp? And his all-around-churlishness? And his bluntess and willingness to think on the fly?) And there have been others: Ross Perot, Bob Kerrey.

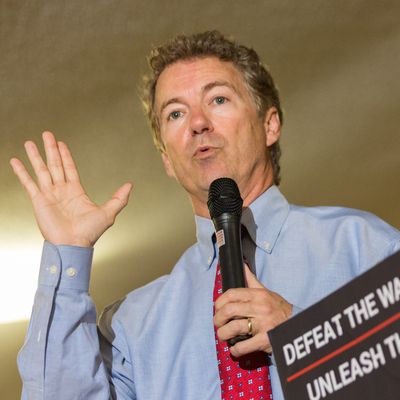

Rand Paul is that guy in this campaign cycle. Less endearing than some of the others, perhaps. But a classic backstage personality, nonetheless. He’s thin-skinned and prickly (especially with female reporters, which is a problem — he shushed CNBC’s Kelly Evans and steamrolled NBC’s Savannah Guthrie as if he were a Sherman tank). A story in Politico this week ago told us he doesn’t care much for glad-handing and fund-raising; he declined an invitation to the Koch brothers’ networking lollapalooza and too frequently (and petulantly) demands time off from the campaign trail. He is outspoken and unapologetic about his libertarian beliefs, like legalizing marijuana (“let’s just say I wasn’t a choir boy when I was in college,” he has said about his own use). He’s unafraid of intellectual provocation, openly questioning the legality of the Civil Rights Act. The way reporters describe him is “interesting.” (Time, the Washington Post, Reason, and Politico all declared him “the most interesting” candidate this cycle, in fact, as Talking Points Memo has noted.) He once set fire to the tax code, nestled in a wheelbarrow, and then crushed it in a wood-chipper for good measure. I suppose one could argue that this gesture was not a backstage-y thing to do, but calculated, a stunt. Here’s the caveat, though: He meant it, and his supporters loved it — this wasn’t an old-timey pol awkwardly picking up a broom and telling the bored crowd that he wanted to clean house.

These guys never make it. Invariably, voters turn on them. We may claim we want authenticity in our politicians, and we do — but not this kind. This kind is too unprofessional, too unpolished, too unpresidential. Like it or not, presidents have never-ending roles to play. The presidency is the Mahabharata of politics, an epic piece of theater for which serious stamina is required.

No, what voters truly want are candidates with permanent front-stage personalities — people with a polished public persona, who actually believe their performing selves, to the point that they play those people even in private. Bill Clinton, for instance. He believes himself at all times, even when he’s lying, and he’s the same fellow in a stadium of 40,000 and a private card game of four. Reagan was the same way (indeed, his private self was so elusive that poor Edmund Morris had to fictionalize the biography he ultimately wrote of him, even though he’d gained unprecedented access to Reagan’s aides and diaries). Even Obama fits this definition. He’s just as measured in private as in public, and just as professorial. He didn’t earn the nickname “no drama Obama” for nothing. (If Americans actually believed Obama had an angry alter ego like the one brilliantly conceived by Keegan-Michael Key, they never would have reelected him. Luther is for our cathartic benefit, not his.)

If front-stage characters are whom we elect, Rand Paul, the polar opposite, would inevitably have to go.

And so, too, by the way, will Donald Trump. Yes, he’s the same in public and in private. But it’s not because he’s uniformly a front-stage personality or a backstage one; it’s because he’s a pathological personality, yanked straight from the pages of the DSM-5. He always speaks his mind, but the things he says are inappropriate in any context — public, private, on the moon. He may speak to a certain portion of the GOP primary base, but in time, he too will combust, as sure as the pages of Rand Paul’s tax code, because the electorate can tolerate screwball, unpredictable behavior for only so long. And when enough of these unsuitable candidates go, when they finally exit stage right — that’s when the primary begins in earnest.