President Obama, visibly angry and frustrated, made his 15th public statement in response to a mass shooting on Thursday night, saying it’s past time for Americans to stop viewing gun violence as routine and take action. He asserted that other nations have already proven that stricter laws can stop mass gun deaths, like Thursday’s fatal shooting of ten people in Oregon. “We know that other countries, in response to one mass shooting, have been able to craft laws that almost eliminate mass shootings,” he said. “Friends of ours, allies of ours — Great Britain, Australia, countries like ours. So we know there are ways to prevent it.”

Australia’s and Britain’s efforts to reduce gun violence in the ‘90s are often cited by advocates and opponents of stricter US. gun control. Here’s a look at how those nations addressed mass shootings, and whether the same policies could work in the U.S.

AUSTRALIA

On April 29, 1996, 35 people were killed and 23 were wounded when Martin Bryant, a 28-year-old man with intellectual disabilities, opened fire in Port Arthur, Tasmania, a former penal colony and tourist destination. After eating lunch at a café, Bryant pulled out a semi-automatic rifle and opened fire, killing 20 people and wounding 12. He then walked to his car, killing several people in the parking lot, and drove off. Up the road he stopped and killed a young mother and her two daughters, ages 6 and 3. Next he hijacked a BMW, killing four people inside, shot the female passenger in a Toyota, and took her boyfriend hostage. After shooting at several people along the highway, he holed up in a cottage, dragging his hostage inside. Following an overnight standoff with police, Bryant set the cottage on fire and ran out. The hostage and the cottage owners were dead.

The massacre shocked and horrified Australians, and in just 12 days the government proposed and passed the National Firearms Agreement and Buyback Program. The new gun laws included a ban on many types of semi-automatic, self-loading rifles and shotguns. Each gun required a separate permit with a 28-day waiting period, and Australia created a national firearms registration system. Guns could only be sold by licensed firearms dealers, and limits were placed on the amount of ammunition that could be sold. Firearm owners had to be 18, complete a safety course, and have a “genuine reason” for owning a gun, such as sport shooting, hunting, or occupational requirements (“personal protection” did not count as a legitimate reason). Licenses expired every five years, and could be revoked if police found “reliable evidence of a mental or physical condition which would render the applicant unsuitable for owning, possessing or using a firearm.”

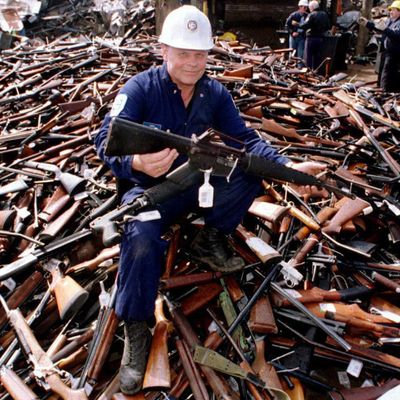

The new laws also included a national gun-buyback program for newly prohibited weapons. The program cost $230 million, which was raised through a small health-insurance tax increase, and ultimately more than 700,000 firearms were purchased by the government or voluntarily handed in. Some firearms weren’t turned in, and in 2012 an estimated 260,000 illegal guns were still in circulation.

President Obama and other gun-control advocates often say that Australia has had no mass shootings in the past 19 years. That depends on your definition of “mass shooting.” The Australian Institute of Criminology describes it as a shooting in which four or more people are fatally shot by a single gunman. In 2002 two people were killed and five were injured in a shooting at Melbourne’s Monash University; in 2011 three people were killed and three were wounded in the Hectorville siege; and last year three people (including the gunman) were killed and four were injured in a Sydney hostage crisis. In the 18 years prior to the Port Arthur massacre, 112 people were killed in 13 mass shootings in Australia.

Some argue that Australia’s homicide rate was already declining before the NFA was implemented in 1996. But in 2012 a study by Australian National University’s Andrew Leigh and Wilfrid Laurier University’s Christine Neill concluded that in the decade after the law was introduced, the firearm homicide rate dropped by 59 percent and the firearm suicide rate fell by 65, with no corresponding increase in homicides and suicides committed without guns.

GREAT BRITAIN

Like in Australia, Great Britain enacted some of the world’s strictest gun-control measures following mass shootings in the late ‘80s and ‘90s. On August 19, 1987, Michael Ryan killed 15 people and wounded 15 others in a series of random shootings around Hungerford, Berkshire. He also killed his mother before taking his own life. The pistol and two semi-automatic rifles he used in the massacre were all owned legally. Ryan may have been suffering from schizophrenia, but no motive was ever established.

In 1996, Thomas Hamilton entered an elementary school in Dunblane, Scotland, and killed 16 children and their teacher before committing suicide. He was also legally allowed to own the two rifles and four handguns he used in the massacre.

In response to the Hungerford massacre Parliament passed the Firearms (Amendment) Act 1988, which banned high-powered self-loading rifles and burst-firing weapons and limited sales of some types of shotguns. Few people owned these weapons, and the law did not significantly affect the rate of gun violence.

More sweeping gun-control measures were passed in 1997. In the months after the Dunblane massacre, 750,000 people signed a petition calling for new restrictions on handgun ownership. Following a government inquiry into how to address the issue, the U.K. banned semi-automatic and pump-action firearms, introduced mandatory registration for shotgun owners, and banned private handgun ownership in mainland Britain. The government launched a $200 million buyback program, which led to the collection of 162,000 firearms.

The effect of Britain’s gun restrictions is less clear-cut than the outcome in Australia. The Hungerford and Dunblane massacres were the only mass shootings in modern Britain prior to 1997, and there was another massacre in 2010, when taxi driver Derrick Bird killed 12 people and injured 11 while driving through Cumbria. Bird, who committed suicide, was licensed to carry firearms.

CNN reports gun crime in England and Wales the late ‘90s increased after the new gun laws were passed, peaking at 24,094 incidents in 2003–04. By 2010–11 gun crime had decreased by 53 percent from that high. Despite Britain’s more mixed outcome, the Washington Post’s Anthony Faiola argued that the legislation did play a role in that drop:

Statistics … suggest that the gun bans alone did not have an immediate impact on firearm-related crime. Over time, however, gun violence in virtually all its guises has significantly come down with the aid of stricter enforcement and waves of police anti-weapons operations. The most current statistics available show that firearms were used to kill 59 people in all of England and Wales in 2011, compared with 77 such homicides that same year in Washington, D.C., alone.

WOULD IT WORK IN THE U.S.?

Following the theater shooting Aurora, Colorado, John Howard, the conservative former prime minister who enacted Australia’s new gun laws, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times arguing that Australia could serve as a model for the U.S. when it comes to curbing gun violence. “Few Australians would deny that their country is safer today as a consequence of gun control,” he wrote. But he admitted that there are very different cultural and legal circumstances in the United States:

Our challenges were different from America’s. Australia is an even more intensely urban society, with close to 60 percent of our people living in large cities. Our gun lobby isn’t as powerful or well-financed as the National Rifle Association in the United States. Australia, correctly in my view, does not have a Bill of Rights, so our legislatures have more say than America’s over many issues of individual rights, and our courts have less control. Also, we have no constitutional right to bear arms. (After all, the British granted us nationhood peacefully; the United States had to fight for it.)

Still, gun-control advocate Rebecca Peters, who campaigned to tighten Australia’s gun laws, argues that the U.S. could take some cues from other countries’ successful efforts to combat gun violence — such as banning assault weapons, expanding background checks, and increasing waiting periods — without implementing gun-control laws as strict as Australia’s. “When you’re talking about reducing motor vehicle accidents, you don’t only rely on seat belts, you don’t only on speed limits, you don’t only rely on highway design, you don’t only rely on motor vehicle standards, but you have a set of them,” Peters told ABC News. “Similarly, they’re a set of measures that together constitute regulation to prevent gun violence.”