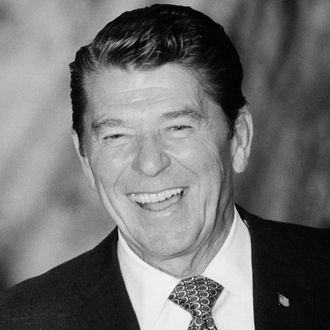

In examining the many possibilities of a “contested” or “open” Republican convention without a locked-down nominee, it makes sense to look at the last time this happened: the 1976 Republican convention, where President Gerald Ford had a plurality but not a firm majority of delegates in his camp when the festivities began, in Kansas City. Today’s Reagan-worshiping Republicans should take particular note of how Ronnie (or, more specifically, his Svengali, the veteran political consultant John Sears) decided to deal with the situation: using the vice-presidential nomination to attract uncommitted delegates and force a rules showdown.

Keep in mind that prior to 1976 the ancient tradition in major-party politics was that vice-presidential choices were made at the convention itself, usually after the presidential balloting. But Reagan announced about three weeks before the confab that if he were nominated his running mate would be Pennsylvania senator Richard Schweiker. This shocked the political world, since Schweiker was, on most issues, one of the most liberal Republicans in the Senate (with a then-recent 100 percent rating from the AFL-CIO’s Committee on Political Education, among other indicators toxic to conservatives). But more to the point, there was a bloc of uncommitted delegates in the Keystone State that Sears thought the maneuver might pull across the line, perhaps even bringing with them some delegates previously committed to Ford.

In the end, most of the Pennsylvania delegation was unmoved, and the ploy probably cost Reagan a shot at winning over a closely divided Mississippi delegation that was voting as a bloc via a unit rule (it annoyed Reagan partisan Jesse Helms so grievously he briefly toyed with an effort to draft New York senator James Buckley as a dark-horse alternative to both Reagan and Ford). But Team Reagan also used the vice-presidency as the basis for a rules challenge that tested Ford’s grip on the convention: a motion to require all candidates to disclose their preferred running mates prior to the presidential balloting. The idea here was that any name he came up with might alienate some Ford delegates (his earlier choice of Nelson Rockefeller as the actual vice-president offended conservatives greatly; Rocky had to disclaim interest in renomination in 1976 to avoid becoming a huge handicap in the primaries). That, too, failed, and demonstrated that Ford had the nomination in hand once and for all.

But the precedent of using a preemptive vice-presidential choice to help win a presidential nomination has lingered in the air as a tantalizing option ever since. And if it were ever going to happen again, this could be the year.

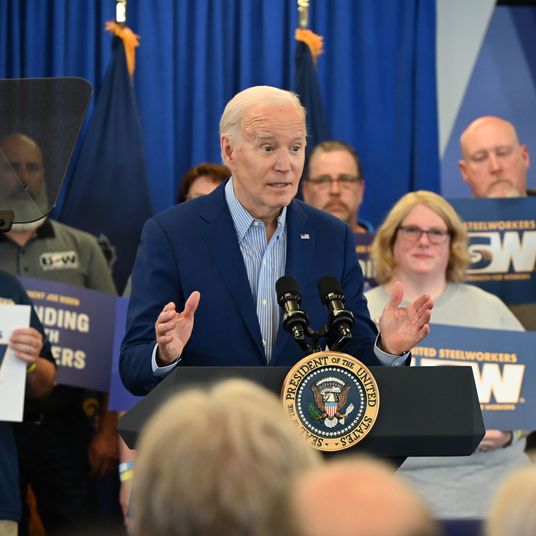

Let’s say Donald Trump is in Ford’s position of leading with a plurality but not quite a majority of delegates, and Cruz is in Reagan’s position of playing catch-up, going into Cleveland — not at all a remote possibility. There would be a pool of “unbound” delegates from an assortment of states, mostly in the West, where state parties have deliberately chosen to keep their options open. If either candidate thought a particular ticket would attract a critical mass of such delegates, would he hesitate to make it? Probably not. More generally, at a time when nervous Republicans will be extremely worried about party unity, purported “unity tickets” will be all the rage. Promising one could be the way Trump nails down the last few delegates he needs for the nomination, or, alternatively, could be the path to a Cruz nomination on a second ballot when most of the delegates become unbound. For those who believe party elites can get away with nominating someone other than Trump or Cruz in Cleveland, a proposed “unity ticket” that would poll well among both Republicans and general-election voters is an absolute must. Moreover, something exactly like the Reagan-Schweiker rules challenge in 1976 to force disclosure of running-mate preferences could happen again in Cleveland, since the presidential candidates will not control all of “their” delegates on procedural matters like convention rules.

Even if Donald Trump nails down a majority of delegates on June 7 with a solid showing in California and New Jersey, naming a running mate whose characteristics show a conciliatory attitude toward the rest of the GOP could be just what the doctor ordered to head off some party coup to deny him the nomination, via a rules change or some other devilish device. Being able to cite chapter and verse from the Gospel of Ronald Reagan as precedent would make a preemptive choice that much more likely. And there will always be some opportunist like Schweiker willing to be used as a key to pick the nomination lock. You can count on it.