Yesterday, a guy named Rurik Bradbury wrote a piece for Esquire’s website called “Why I’m Joining the Innovation Party.” The impetus was an asinine Wall Street Journal op-ed by Politico CEO Jim VandeHei arguing, basically, that Mark Zuckerberg should run for president — in other words, a ripe target for the kind of guy who runs a Twitter account parodying tech-industry new-media snake-oil bullshit.

If you’re the kind of person whose job, or, worse, interests lead you to read a lot of very similar (but actually earnest) essays on Medium about the future of technology, media, tech media, media tech, disruption, or innovation, the Esquire post was a funny bit of satire. The Esquire piece included “thinkfluencer” gibberish like:

The Innovation Party will be phablet-first, and communicate only via push notifications to smartphones. The only deals it cuts will be with Apple and Google, not with special interests. We will integrate natively with iOS and Android, and spread the message using emojis and GIFs, rather than the earth-killing longform print mailers of yesteryear.

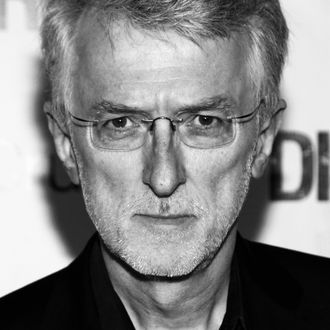

The byline on the piece was “Prof. Jeff Jarvis.” Here’s where it got tricky: “Prof. Jeff Jarvis” isn’t former Entertainment Weekly editor and well-known future-of-media pontificator Jeff Jarvis. Rather, it’s a character developed in a parody Twitter account run by Bradbury. Well-known in certain media circles, @ProfJeffJarvis initially satirized the thoughts of Jarvis himself before growing into a more general and very funny riff on the pie-in-the-sky gambits of new media.

The piece has now disappeared from Esquire’s website, apparently because the real Jeff Jarvis, also a journalism professor, “emailed […] Hearst executives” who “brought in other editors,” setting up a chain of events that seem to have resulted in the piece being removed entirely.

Jarvis (real) has frequently complained about Jarvis (prof), and Jarvis (prof) has frequently fooled well-meaning interlocutors, like the economist Nicholas Nassim Taleb and, once Twitter CEO Dick Costolo, into believing he’s Jarvis (real). Last December, a similar bit of satire was pulled from the Al-Jazeera America website; in 2014, real Jarvis wrote a post on his website, BuzzMachine, “What Society Are We Building Here?”

But now he’s really had enough. You can tell he’s had enough because he wrote a Medium post titled “Enough,” in which the real Jarvis took aim at his doppelganger.

Keep in mind that most people don’t spend more than 15 seconds on a web page — according to Chartbeat — and so those folks would come and see that someone named Professor Jeff Jarvis — oh, that’s my name — said these incredibly stupid things praising incredibly idiotic op-ed and they’d move on.

A parody subject’s quest against his satirizer is, generally, quixotic. One of the most famous First Amendment cases of the 20th century involved the Reverend Jerry Falwell suing Hustler over a parody ad. Falwell lost, and Jarvis would have a similarly difficult time trying to sue Bradbury. And, maybe more importantly, complaints about a smaller and less well-known person’s not-particularly-cruel parody tend to fall on deaf ears. Especially if those complaints take on the apocalyptic tenor of “What Society Are We Building Here?” And especially if the complainant is a professor of journalism.

But, well, the thing is, Jarvis actually has a point — not that the post should be removed, or that the parody is particularly cruel, but that web users, by and large, take things at face value. It’s why fake news is such a viable market and parody accounts pretending to be quote-unquote “epic” comedians like Will Ferrell and Bill Murray proliferate. Before the piece was taken down, Esquire qualified the fake Jarvis’s byline with the phrase “A Well-Known Satirist,” except no, nah, nope. To expect the readers of a mainstream national magazine to understand @ProfJeffJarvis’s whole schtick is assuming a bit much.

There are different barriers to discovery on different platforms. You might find @ProfJeffJarvis on Twitter, where a retweet from a friend or a passing @-mention work as personalized endorsements from those you already know. That is an entirely different form of discovery than seeing his byline on the front page of Esquire.com.

Satire leans heavily on its imagined audiences: people who “get” and applaud the joke, and people who don’t, but for whom the joke should be instructive. On the web, though, it’s much harder to direct your work toward the right set of people. Your possible (and even likely) readership is everyone with an internet connection. Your satire is being read not just by people who “get” it and people who don’t but should, but also by people who don’t have any idea what “it” is. And it certainly doesn’t help that this all happens in text form. Maybe the only site doing it well is the Onion, and that’s partially due to their legacy status. The problem (“problem”) has gotten to the point where Facebook attempted to introduce a [SATIRE] tag to automatically alert users to sarcastic articles. It was a great idea that was extremely effective and everyone loved it.

Will Ferrell can afford to have a parody account, because he’s a famous celeb not trying to position himself as a new-media expert. Jarvis — who has even been consulted by this writer on one occasion — doesn’t have that luxury. Which, again, is not to say that the fake Jarvis did not write a very funny piece or that it should have been retracted! Only that it suffered from a cardinal sin of blogging: assuming that the reader understood the joke.