It feels a bit strange to say this now, but in the spring of 2014 there was no better place to work than Gawker. For a certain kind of person, at any rate — ambitious, rebellious, and eager for attention, all of which I was. Just over a decade old, Gawker still thought of itself as a pirate ship, but a very big pirate ship, ballasted by semi-respectable journalism, and much less prone to setting itself on fire than in its early days, when its writers had a tendency to make loud and famous enemies and when its staff was subjected to near-annual purges — unless they were able to dramatically quit first. It managed to be, in a way it never had been, the kind of place about which you could say, “I could see myself being here in ten years.” Which I did often enough for it to seem funny now, since I myself would end up dramatically quitting in the summer of 2015, a little more than a year after being promoted to editor-in-chief and a little less than a year before the company would declare bankruptcy and auction itself off to the highest bidder.

What Gawker was depends a lot on whom you ask, but at the start it was a media-gossip blog; Elizabeth Spiers, its first editor, covered the people and politics of the still-powerful institutions of New York media — Condé Nast and the Times in particular — with equal parts obsession and skepticism. But the “media” qualifier was always secondary to the gossip core. The noblest version of Gawker’s premise was — as its founder, Nick Denton, repeated many times — that the version of a story journalists would tell each other over drinks was always more interesting than whatever was actually in the paper.

Gawker wasn’t the first publication to treat gossip as an intellectual pursuit. But it was the first to do so in the format that now seems completely natural for it: an endlessly scrolling, eternally accessible record of prattle and wit and venom that felt less like a publication than like a place. In this sense, the hook of Nick’s “barroom story” elevator pitch wasn’t the story but the barroom: a loud, sociable space for people to gossip, argue, joke, and whisper, a place where decorum and politeness were not only unnecessary but actively objectionable.

To what Vanessa Grigoriadis called in New York Magazine, in 2007, “the creative underclass,” this was a revelation. Gawker was as obsessed with, and scornful of, the powerful as the editorial assistants, interns, freelancers, and other young and precariously employed people at the bottom of a rapidly deteriorating ladder were. As an intern at the Daily Beast in 2009, I read Gawker precisely because it had such gleeful disdain for the social rituals (“kindness”) that propped up the lame, the stupid, and the fraudulent. When I was given the opportunity to “audition” for a blogging job in 2010, the only thing that gave me pause was fear of Gawker’s reputation for instability and pressure.

That pressure had, however, produced a phenomenally successful publication: By 2014, Gawker was the anchor site of Gawker Media, a blog network with eight publications, some 300 employees, millions of readers, and countless imitators. I was told, my first week as editor-in-chief, to increase the size of the staff from 13 to 25; at the same time, the endless hunt for a new office was ending with a Fifth Avenue building in our sights. (It violated the primary edict of being in walking distance from Nick’s apartment, but we’d been rejected from the Puck Building, we were told, after Oscar Health founder and Ivanka Trump brother-in-law Josh Kushner, who held offices there, learned we were interested.)

Gawker, and its seven sister sites, had been so successful that we were even looking beyond the blog and into the future with a project Nick had dubbed Kinja. Practically, Kinja was just the proprietary publishing software and commenting system that had been introduced on the blogs in early 2013. But Nick had Facebook-size aspirations for it. In the future, it would be a public platform, designed to give anyone the ability to publish useful information — gossip, news, context — in an infinitely modular format: a stand-alone piece of writing that might also be a comment on another stand-alone post or embedded in a third. Over emails, Nick imagined “at least a decade” of building Kinja — at the end of which, if done right, “we’ll be the ones doing the acquiring.”

In August 2014, the editors-in-chief of Gawker Media’s sites and their deputies were flown to Budapest with the entire tech department and top advertising and operations employees for a lavish off-site meeting. Nick rented out the newly constructed Budapest Music Center, where the tech and product teams spent their days working out Kinja’s kinks while the editorial staff met to vision-board the future of Gawker Media’s editorial properties. The whole trip had the air of a coming-out party: a moment to recognize that a company launched in an apartment with no outside funding was now a sustainable, cash-rich institution. We were meant to revel in Gawker’s success — to go out drinking, to eat roast pig, to gamble at low-rent casinos, to retire to nice hotels in a European capital.

Within two years, Kinja would be abandoned, along with Nick’s world-conquering ambitions, and ultimately the entire company would declare bankruptcy and be sold at auction to the media conglomerate Univision for $135 million. Gawker Media will likely turn out to be a good investment. Its six other sites — Gizmodo (tech), Jezebel (women), Deadspin (sports), Lifehacker (life-hacking), Kotaku (video games), and Jalopnik (cars) — are large and widely popular. (An eighth site, io9, covering “the future,” had already been folded into Gizmodo.) The parent company is on pace to earn more than $50 million in revenue this year. As much as a third of that revenue comes from the lucrative e-commerce department, which makes money from links to Amazon and other retailers.

But Gawker itself was deemed too toxic to keep open. Within days of the sale, Univision announced it would shut down the site. It makes sense; no sane corporate owner would ever give Gawker the same kind of long leash that it had under Nick. And without that absolute editorial freedom —especially the freedom to shoot itself in the foot, while its foot is in its mouth — there is no Gawker. Gawker had “died” a dozen times before. But it’s never died like this.

The question remains, who killed it?

1. Nick Denton

Much of that (somewhat unnerving) sense of stability in 2014 could be chalked up, surprisingly, to Nick. A tall, imposing Brit with an intimidating tolerance for awkward pauses and an unquenchable thirst for gossip, Nick Denton had long maintained a reputation as a villain in New York media circles, a dark prophet who had appeared at the twilight of journalism to reveal a new path. He’d arrived in New York City in 2002 after stints as a financial journalist and tech founder, carrying with him the British reporter’s disdain for propriety and the Silicon Valley entrepreneur’s contempt for rules. He took a small dot-com fortune made from a tech meetup site and used it to fund payments — $1,000 a month — for writers at two blogs. One was Gizmodo, a digital Wired focused entirely on consumable electronic gadgets. The other was Gawker.

As Gawker grew from a curiosity to a threat to a powerhouse, so too did the legend of “Nick Denton”: a forbidding, humorless crypto-sociopath who pushed his employees to the limits of their ability (physical, ethical, and, given how low the pay was initially, financial). Like all characters, the “Nick Denton” of Gawker was exaggerated, but not by much; Nick was utterly unsentimental, about both his employees and the traditional work of journalism. Once, seemingly on a whim, he published a lengthy post detailing the recent romantic life of Emily Gould, a star Gawker writer who had abruptly and publicly quit the site three months earlier. “[I]t’s a good yarn, of the romantic and professional entanglement of New York’s literary and media networks, so fuck it,” he wrote. He was fond of iconoclastic proclamations. “Originality is overrated,” another email subject line read, implicitly praising the Daily Mail’s habit of, in the words of veteran British editor Simon Kelner, “shamelessly borrow[ing] from other media.”

I admired this unsentimentality, which, whatever else you might think of it, had created one of the most surprising and exciting online publications. But by 2014, the character of “Nick Denton” had less and less of a relationship to the Nick Denton with whom we worked at the office. He was in love —he’d marry his fiancé, Derrence Washington, an actor, at a large party at the American Museum of Natural History. He was in therapy. He was still hard to talk to, just not in a scary way: Over lunch, we’d discuss the news, he’d ask about my girlfriend, and then he’d tell me, as I poked at my expensive salad, about gay “bottom shame.” He’d also hired for the first time a day-to-day manager for the blogs, former Gizmodo editor-in-chief Joel Johnson, who became editorial director, freeing Nick to plot the company’s future.

And he was smoking marijuana. Not really an absurd amount of it, relatively speaking, though many Gawker staffers have nightmare stories about the potency of the stuff he kept around his cavernous Soho loft. Of course, it’s not the pot that made Nick a kinder boss and more sympathetic person. It’s some combination of the many changes that accompany age and success: a loving relationship with someone who by all accounts doesn’t give a shit about the petty power struggles of media moguldom; a level of self-actualization that made him more empathetic; a desire, perhaps, to attend cocktail parties with his peers without being regarded as a scourge or a villain; and a broader and more forgiving view of the world as a whole.

Well. The pot helps, maybe.

Pot also provides a kind of convenient metaphor. At the height of Nick’s mania for Kinja, the running joke around the office was that Nick was taking a company built on cocaine and trying to turn it into a company run on marijuana. The frequent emails we used to get about maximizing our audiences and improving our story packaging were replaced with exhortations to invite the subjects of our posts into the comments for engaging conversation. I still have a treasured text chain between Nick and some product people helping develop Kinja, in which Nick earnestly compared a hypothetical perfected Kinja to the scenes in the X-Men movies where Professor X searches out mutants in his enormous helmet. This seemed to have very little relationship to the commenting system at the time, which was being used mostly by people with screen names like “MaxReadIsDogShit.”

But to the extent that I could see through the fog of comic-book references, Kinja still made sense as a Gawker vision: We were building a free-flowing, freewheeling platform for gossip to be distributed, analyzed, contextualized, and reported out. That felt Gawker to me.

Less Gawker were Nick’s simultaneous attempts to turn his company into what we sometimes jokingly called a “real company”—that is, a respectable, sustainable business. Some of these efforts were well received: the creation, for example, of an actual human-resources infrastructure. Some were perplexing but gladly received — a successful drive to unionize the editorial department was greeted with open, if stiff, arms by Nick. What was most welcome, at least at first, was Nick’s growing sense that the blind pursuit of traffic was slowly turning his sites dim-witted and uninteresting. At the same time, Gawker was — by Nick’s measurements, at any rate — too infrequently “at the center of the conversation.” His solution was characteristically Dentonian: He fired his longtime friend Joel, replacing him with Deadspin editor Tommy Craggs, and announced, in a lengthy memo, that there would be “less pandering to the Facebook masses.”

This would be accomplished not by abandoning metrics but by new metrics. He became intently focused on the number of Gawker Media stories that appeared on his Nuzzel — an app that sends a daily digest of stories, sorted by how many of your followers had tweeted out the stories. (The logic being that the people Nick followed on Twitter were the best approximations of “the conversation.”) By the summer of 2015, a group of managers were being sent a daily email showing a “buzz” score, calculated by how many outlets — weighted by prestige — were writing about or linking to Gawker.

As he was attempting to nudge Gawker back into the conversation, Nick was also insisting that Gawker itself was too mean. Nick always had a strong sense that there is a line Gawker shouldn’t cross; the problem was he’d never been able to articulate where it was. In a post from 2007, former editor Alex Balk remembered Nick instructing him to be “aware” of the site’s “not undeserved” reputation for “being needlessly cruel,” then minutes later proposing stories: “Who’s shorter in real life than you think they’d be? Who has dandruff?”

By 2015, he had taken to insisting that Gawker, under my editorship, was the meanest it had ever been. He hated one feature called “Baby Name Critic” — a satire of content-farm coverage of celebrity-baby names that took the form of critical evaluations in the style of a book or movie review — so much that he once appeared in the comments fretting that Zoe Saldana’s newborn twins — Cy Aridio and Bowie Ezio — might someday Google themselves and feel wounded that writer Leah Finnegan had called them “hipster scum.”

Nick had spent ten years crafting, and supporting, an editorial ethos and culture, not to mention a public persona, predicated on frankness, fearlessness, and, yes, sometimes, cruelty — and was now trying to change its course by objecting in the comments of his own writers’ posts. This was top-down, institutional schizophrenia, and it was inevitable that it would resolve itself messily.

2. Me

Then again, maybe Nick was onto something. Traditionally, the direction of the “punch” has determined whether a satirist’s jokes were on the side of good or evil. Punching up: That’s righteous. The opposite is just cruel.

But direction can be hard to determine for the internet. Zoe Saldana’s twins are young, and Leah Finnegan could almost certainly beat them up. On the other hand, Zoe Saldana’s twins have been born into a life of leisure that gives them the means to hire a bodyguard to beat up Leah Finnegan, should they so choose. In which direction was Leah punching? (I mean: Was she even “punching” at Saldana’s kids at all?) The nature of “the platform” has changed, too. If anyone on Twitter or Facebook — or, theoretically, Kinja — can obtain the same-size audience as Gawker, is it fair to say that Gawker is more powerful?

If I was supposed to, as editor-in-chief, determine the direction of the many vectors of power, I failed. I liked critical Gawker; I liked the idea of an internetwide alt-weekly bent on criticizing the powerful in as colorful terms as possible. This felt especially true since the rise of venture-funded sites like Vox and BuzzFeed had brought about an era of safe, deferential internet writing, against which Gawker’s (still fairly infrequent!) spite seemed — internally, at least — like a moral necessity. If this was an overdramatic, Manichaean understanding of the world, well, then it was all the more Gawkeresque.

The debate at Gawker wasn’t just about the allowable degree of meanness; it was about what constituted meanness to begin with. To the general public, to say Gawker was “mean” often meant not just that it was petty or disrespectful but that it was unfairly invasive — such as Gawker’s reporting that Fox News anchor Shep Smith was gay and dating a younger co-worker. But Nick never thought of the publication of details about the private lives of public subjects as “mean”; in fact, he largely saw it as noble. “Every infringement of privacy is sort of liberating,” he told a Playboy interviewer in 2014.

Rhetorical cruelty was another matter, and this was where he and I tended to disagree the most. Was it “mean” to say — for example — that the Times’ “Style” columnist Nick Bilton was “the new worst columnist at the New York Times”? Did it become less mean when Bilton later published a column about cell phones and cancer sourced to a quack doctor? If we published a post called “Bristol Palin Makes Great Argument for Abortion in Baby Announcement” — written after a mournful post on her blog that made it exceedingly clear that Palin didn’t want to have the child—was that needlessly cruel? Nick sure thought so: After that post, he texted my boss, Tommy Craggs, to say he was “ashamed” of Gawker’s “callow viciousness” and “hate[d] the culture of Gawker.”

It should be said that Gawker in 2015 really wasn’t very mean. The vast majority of what we published was opaque or weird or stupid. But bluntness and meanness are so rare that they stick in the minds of readers. Between its infrequency and Nick’s pressure, “meanness” took on an outsizeimportance — an endangered legacy we felt compelled to protect.

So I resisted at length, and I think justifiably, Nick’s pressure, which was easy enough since Nick knew he had encouraged his writers’ and editors’ independence for too long to bring them to heel now.

That editorial independence was an important component of what set Gawker apart, but it created a culture in which we were often writing as much for each other, in endless cycles of one-upsmanship and self-reference, as for an actual audience. This is a familiar dynamic in web publishing. Enough dismissive or hateful comment threads, enough disingenuous or overstated outrage, enough undermining emails from an imperious and often humorless boss, and you begin to feel like the only people who really get what you’re doing are your co-workers.

Which is in part why when a tip dropped into our laps that a married (to a woman) C-suite executive at a prominent media company had attempted to set up an assignation with a Chicago rentboy, I jumped at it. Here was an Old Gawker story of the kind Nick had once defended: the sexual foibles of a powerful executive and member of a ruling-class family. It would be nice to say that I struggled with the ethics of publishing the story, or that, even better, my maniacal and sociopathic boss pressured me into publishing it. But there was very little question in my mind: It seemed so naturally a Gawker story that I assigned it immediately.

Of course, it wasn’t a Gawker story. We’d rushed the article to publication in part because Nick was having a party at his apartment that evening and I felt like it would be nice to have a scoop to show off. Instead, what I brought was a nuclear reactor. The article, which named the executive, was so quickly and thoroughly despised, and I was so ready to fight with its objectors, that Tommy forcibly took my phone out of my hands and deleted Twitter for me. I woke up the next morning to a full-fledged internal crisis. Within 24 hours of the story’s publication, it was clear that I was not long for Gawker. The following Monday, Tommy and I submitted our resignations.

At the time, I felt furious — like I’d been forced out to the edge of a tree branch, only to turn around and see the man who pushed me out there sawing it off. But the truth is I had gone out on the limb because I liked it out there. I liked being the villain, the critic, the bomb-thrower. If one of my bombs went off in my face, it was only my fault.

I could construct (and, during the past year, often have, over sheepish drinks with disappointed or angry colleagues) an elaborate house of rationalization, wings upon wings of explanation about the value of transparency, the democratic significance of holding nothing back. But ultimately we’d put to work a tactic best used to shame homophobic politicians against a guy whose only real crime was being a member of our abstract notion of the enemy class. We hadn’t exposed any great hypocrisy; instead, we’d taken a bit of gossip and brought the full bludgeoning of moral urgency and ideological commitments to bear on it.

Whatever we’d hoped to accomplish with that story, we instead reaffirmed the world’s understanding of what we were: needlessly cruel. Within a week of publication, Nick was promising in interviews a “20 percent nicer” version of Gawker. In November, he announced in a memo that Gawker would shift from general gossip and tabloid news to “political news, commentary and satire.”* The tide of public opinion had changed, and Gawker’s mischievous gossip was no longer a guilty pleasure. It was a problem.

3. Gamergate

Of course, “public opinion” online is hard to gauge, since it tends to be determined by the loudest and most persistent voices. If you can mobilize and engage even a fairly small number of people, you can create an impression of enough outrage to destabilize a business. As Gawker was imploding in the summer of 2015, a group of teenage video-game enthusiasts was throwing gasoline on the already-raging fire. These were the Gamergaters.

Of all the enemies Gawker had made over the years — in New York media, in Silicon Valley, in Hollywood — none were more effective than the Gamergaters. Gamergate, a leaderless online movement dedicated to enforcing its own unique vision of “ethics in journalism,” had first taken up with Gawker Media the summer before, in 2014. Earlier that year, a writer for Kotaku had had a brief fling with a well-known video-game developer. In August, the developer’s ex-boyfriend, a 24-year-old computer programmer, wrote a 10,000-word blog post about her, spawning rumors that she’d traded sex for a positive review of her game on Kotaku. That no such review ever actually appeared on the site should tell you a lot about Gamergate’s relationship to the truth; that Gamergaters believe this is how sex works should tell you a lot about the Gamergate demographic. But none of the specifics of the story really mattered, because ultimately Kotaku was being targeted less for specific ethical violations than for its critical coverage of the portrayal of women and minorities in video games and the sexism of the gaming community. The teenagers behind Gamergate were young, obsessive, deeply resentful of women, and had no sense of social boundaries, and now they finally had a rallying cry —“Ethics in journalism!” — and a common enemy — or, really, enemies, among them the developer in question, Zoe Quinn, and feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian, who became the object of both sustained harassment and violent threats.

That fall, Gamergate began waging a hugely annoying, and sometimes genuinely menacing, war against Kotaku. I personally came to the attention of Gamergate in October 2014, not for a fearless act of journalism, but because I was messing around on Twitter and I stepped in it. Sam Biddle, one of Gawker’s best and most notoriously aggressive writers, had tweeted that the lesson of Gamergate was that nerds should be bullied into submission; this in turn led to a flood of tweets and emails to me demanding that he be disciplined; I responded in a mode that seemed appropriate: I goaded and dismissed and largely treated the people complaining with a great deal of contempt and flippancy.

In retrospect: This was extremely stupid. Even in 2014, Twitter had already become a mechanism by which indiscreet people lost their jobs. Still, it was very difficult for me to believe that anyone genuinely thought that “pro-bullying” is a stance that anyone has ever adopted, or that Sam Biddle’s tweet was a statement in support of bullying. But what I believed, or didn’t believe, didn’t matter. I wasn’t messing around with irony-fluent trolls but with teenagers and college students who seemed unable or unwilling to understand context or sarcasm — exactly the kind of people who might actually believe that Sam Biddle would get a raise for bullying gamers (a myth that still floats around the various Gamergate communities).

More problematically, it would turn out, I was also, unconsciously, messing with the only group even less able to grapple with irony or context: brands. What I’d missed about Gamergate was that they were gamers — they had spent years developing a tolerance for highly repetitive tasks. Like, say, contacting major advertisers.

On Reddit, a campaign was launched to contact every advertiser Gamergaters could find on Gawker’s site — and not just the marketing departments of advertisers like Adobe and BMW, but specific executives. If you can bug a chief marketing officer, it doesn’t matter that your complaints are disingenuous: He just wants to stop being annoyed.

And so Gawker went into full-on crisis mode. Our chief revenue officer flew to Chicago to meet shaky clients; someone I hadn’t spoken with since high school Facebook-messaged me to let me know that her employer, L.L.Bean, a Gawker advertiser, was considering pulling its ads. Nick asked me to draft a non-apology apology — a clarification, basically, that we did not, institutionally, support bullying. Sam was compelled to tweet an apology. Joel, then the executive editor, published on Gawker, over the objections of the editors, another clarification. I then published, without Joel’s knowledge, an apology for the apology. Perhaps tellingly, it was the first time I’d ever really been confronted with the business side of Gawker besides small talk at parties.

Then it all went away. Gawker had taken a hit — thousands of dollars of advertising gone, at least. But in the weeks we’d been hemorrhaging advertisers and goodwill, stories in the New York Times and other outlets — the real media—and a segment on The Colbert Report made it clear that the Gamergaters were the bad guys in this case, not us. The sites went back to normal.

But of course it didn’t go away. Gamergate proved the power of well-organized reactionaries to threaten Gawker’s well-being. And when Gawker really went too far — far enough that even our regular defenders in the media wouldn’t step up to speak for us — Gamergate was there, in the background, turning every crisis up a notch or two and making continued existence impossible.

4. A.J. Daulerio

That the financial pressure had reached the limits of bearability was in large part because looming on the horizon was an enormous and costly lawsuit, one that Gawker expected to win even as it was being thwarted at every turn.

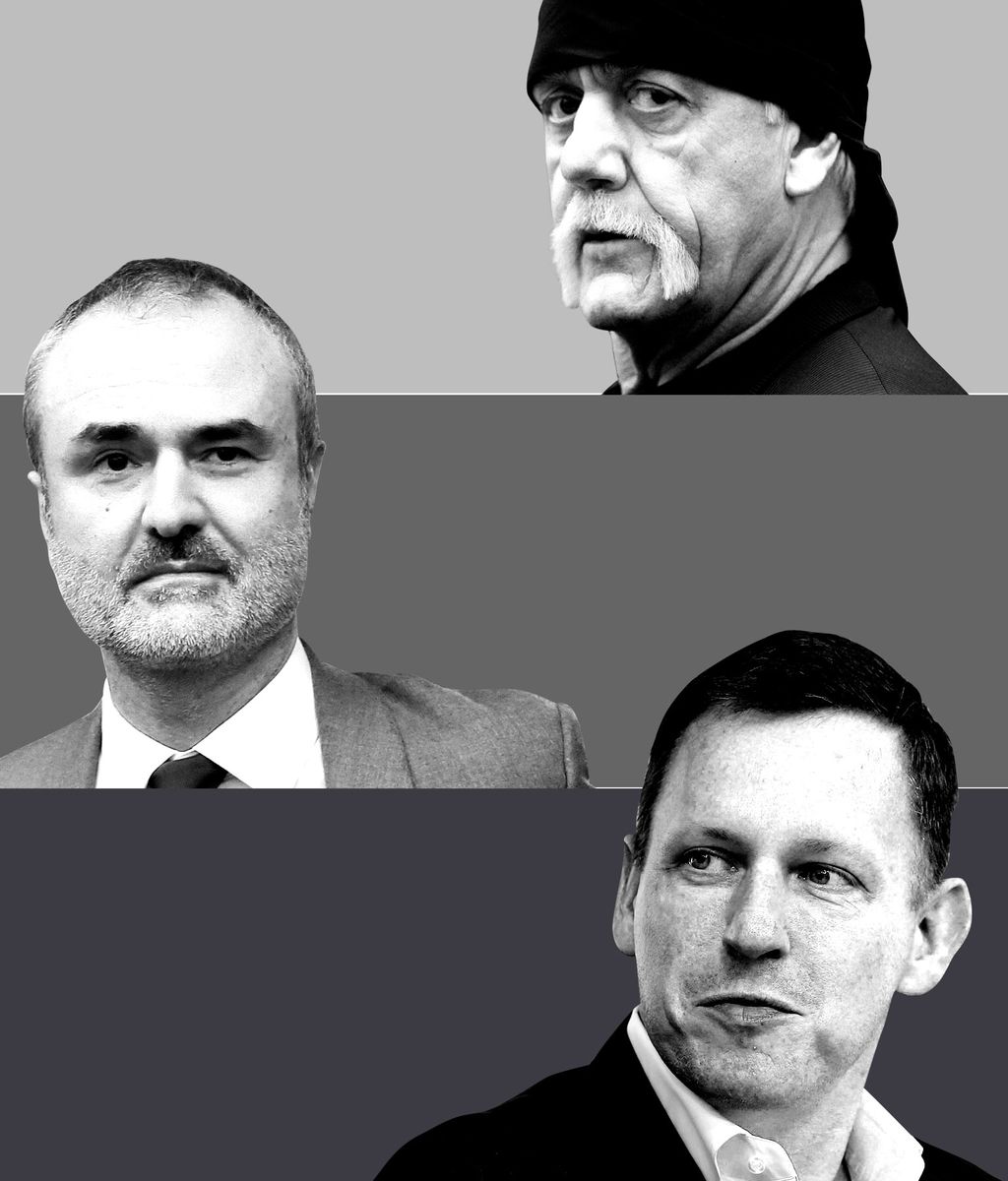

In 2012, A. J. Daulerio, then the editor-in-chief of Gawker, published an article with the unwieldy title “Even for a Minute, Watching Hulk Hogan Have Sex in a Canopy Bed Is Not Safe for Work but Watch It Anyway.” At the top of the post was a grainy, 101-second video of the wrestler Hulk Hogan with Heather Clem, the wife of his friend Bubba the Love Sponge, a Florida radio personality. Nine seconds of the video featured actual sex; the bulk showed Hogan and Clem engaged in small talk after the act.

Hogan sued Gawker, Nick, A.J., Clem, and the Love Sponge, who’d recorded the tape himself. (Bubba initially claimed that Hogan had been aware he was being recorded but insisted he wasn’t the person who’d leaked it.) The judge who took up the case in 2013 ordered Gawker to remove the post. Gawker, citing the First Amendment, declined, though it did take down the video itself, and in March 2016, four years after the original post had been published, the suit moved to trial in front of a Florida jury.

The trial was a disaster, not least because of A.J. himself. A deposition recorded in 2013, when it still seemed likely that the suit would end in a settlement, featured a damaging exchange in which a lawyer for the plaintiff pushed A.J. about the lines Gawker would or would not cross, asking: “Can you imagine a situation where a celebrity sex tape would not be newsworthy?” “If they were a child,” A.J. says. “Under what age?” the lawyer asks, a dumb question that deserved a more serious answer than A.J.’s flippant response: “Four.” The jury ruled in favor of Hogan, awarding him $140 million. A.J. was held personally liable for $100,000. His net worth was calculated to be -$27,000.

A.J. is now thought of as the guy who revealed the sociopathy at the heart of Gawker — but I mostly remember him as a great boss. Deadspin, the site he ran, was funny and weird and smart. It seemed to hit perfectly that characteristically Gawker balance between high- and gutter-mindedness. He’d turned what could have been a boringly sordid story about the Jets’ then-quarterback Brett Favre’s allegedly sending dick pics to a Jets female employee into an entertaining, multi-post saga in which A.J. was a main character and which included publishing the pics themselves — in the process burning his source and paying money for material. It was reckless and stupid and useless and thrilling, and it also raised a real concern about a famous football player sexually harassing women. This was what Gawker was supposed to be doing, right? Not just juicy, populist, tabloid stories —juicy, populist, tabloid stories with panache, and a point.

This was A.J.’s role, as much as anything: to be the Gawker about which people told tall tales. But he also recognized talent and encouraged it to succeed; he hired and put in positions of responsibility more women and people of color than any editor before or since. Instead of asking a diverse array of writers to meet similar traffic goals, he treated traffic like its own particular beat and hired a writer, Neetzan Zimmerman, to cover that beat, seeking out and writing up the highly viral content that would help the site reach its monthly targets while other writers pursued their weird interests at their own speeds. He understood his job as assembling a team of writers he loved to read and giving them the cover to pursue their ambitions.

The problem for A.J. is that at Gawker, “cover” often meant being scummy and reckless so the staff wouldn’t have to be. He’d already demonstrated a willingness to cross lines of taste and ethics at Deadspin, most notoriously when he posted a video of a drunk woman having sex in a bathroom stall and stonewalled her requests to remove it (he ended up taking it down the next day; he later told GQ he regretted publishing it). At Gawker, he left the traffic obligations to Neetzan and the day-to-day editorial operations to his gifted junior editors, 24-year-old Emma Carmichael and 25-year-old Leah Beckmann. (This was a familiar dynamic at Gawker, where male employees were generally encouraged to be impulsive and reckless, while female employees were expected to pick up the actual work of maintaining a continuously operating website.) Meanwhile, A.J. continued to fulfill the pushing-the-boundaries obligations. When Nick asked him why he wouldn’t publish whatever recent rumor Nick had heard about a celebrity being gay — a common entreaty to Gawker editors — A.J. introduced a sarcastic column called “Gay or Not Gay?” under his byline. And when a Hulk Hogan sex tape landed in A.J.’s lap, A.J. published it, because that was the cost of doing business.

And then the cost of doing business turned out to be $140 million.

5. Peter Thiel

Among the most frustrating things about the Hogan lawsuit, as it slowly marched toward trial, was that no one who hadn’t worked for Gawker seemed to have any sympathy for the company. Many people had adopted the line that the post itself, despite having passed with little comment in 2012, was a bridge too far — “revenge porn” of the kind that had ruined the lives of people who weren’t professional wrestlers. But the specifics of the post were ultimately irrelevant; it had become a stand-in for whatever past sin had most offended you. Gawker once unforgivably outed a little-known media executive, or was cruel to me or one of my friends, or was a white-guilt propaganda outlet dedicated to the destruction of gamers; for this, it deserved to suffer. If Hogan was the agent of that suffering, so be it.

But the Hogan case was weird. In most lawsuits like this, where the defendants have a strong free-speech case and a payout is far from guaranteed, plaintiffs are looking to come to a settlement: a decent-size sum and the removal of the offending post. But Gawker and Hogan couldn’t, or wouldn’t, come to an agreement. It’s possible Hogan was willing to face a jury because he’d managed to get the case tried in his hometown, where he enjoyed status as a local hero. Or maybe he was willing (or obligated) to risk trial because someone else was bankrolling his legal team. By the time speculation that Hogan’s persistence could be chalked up to an outside backer began to circulate at Gawker, I was gone; I heard later that the first guess was the Church of Scientology. But by this past winter, there was only one real suspect: Peter Thiel.

Thiel is, by most accounts, remarkably similar to Nick: a gay European immigrant; a conservative libertarian; a future-obsessed, cerebral visionary prone to conversational awkwardness. They ran in similar circles in the Bay Area in the early aughts. The year Nick moved to New York, Thiel sold PayPal to eBay for $1.5 billion and soon after invested $500,000 in Facebook. Three years later, in 2007, Owen Thomas, blogging for a now-defunct Gawker site, Valleywag, wrote a post called “Peter Thiel Is Totally Gay, People.”

It’s a largely compassionate post. Thomas, who is gay himself, writes about the unspoken bigotries of California venture capital that, he speculates, led Thiel and his friends to rarely discuss his sexuality, and makes a case that expanding the circles to which Thiel was out is a social good, that “it’s important to say this: Peter Thiel, the smartest VC in the world, is gay.”

Thiel evidently didn’t agree. Soon after the judgment, Thiel admitted to the Times that he was behind the lawsuit, which he described as “less about revenge and more about specific deterrence” against Gawker’s “bullying.” The revelation that Thiel had been the agent of so much of Gawker’s humbling was grimly satisfying; at least Gawker’s downfall wasn’t just the result of its own recklessness — it was also due to the efforts of a flatteringly devoted enemy. But knowledge of Thiel’s identity had no effect on the result. It was like an episode of Scooby-Doo where the old man disguised as a ghost still gets away with it.

6. The Internet

Not so long ago, it was actually sort of okay to publish a short excerpt from a celebrity’s sex tape to your otherwise mainstream gossip blog. “Okay” is relative here, of course. There were certainly people in 2012 who thought A.J.’s post a gross violation of Hogan’s privacy. Still, the extent of mainstream condemnation was cheeky expressions of disgust — physical, not moral. The Times devoted an item to the post, quoting tweets from Bill Maher and Zach Braff.

What was okay (if naughty) in 2012 is, in 2016, regarded as indefensible. The reaction to the enormous judgment against Gawker makes it clear where public opinion now lies: in sharp if muddled defense of privacy rights, even for public figures.

But what has changed isn’t just the outer boundary of what’s appropriate to publish, but where it can be published. Gawker’s biggest mistake in a way was that it had failed to realize that it was no longer the bottom-feeder of the media ecosystem. Twitter and Reddit and a dozen other social networks and hosting platforms have out-Gawkered Gawker in their low thresholds for publishing and disregard for traditional standards, and, even more important, they distribute liability: There are no bylines, no editors, no institution taking moral responsibility for their content. Or, for that matter, legal responsibility — U.S. law protects social networks from liability for the content posted by individual users. These sites had hollowed out a space below Gawker just as Gawker, with great reluctance, had become a real media outlet, one large, rich, and slow-footed enough to be held to account — and taken down.

In mid-August, the bankruptcy auction looming, Nick threw a party at the still-newish Fifth Avenue offices. The party was called “Against All Odds” — referring, presumably, to the 14 years of Gawker Media’s success, not its fiery and dramatic downfall, which I think most of us in attendance had imagined was inevitable. An hour or so into it, Nick took the floor to give remarks to a crowd of current and former Gawker Media editors, writers, coders, sellers, hangers-on, and subjects. “The fact that we’re here is a freakin’ miracle,” he said, as a Gamergate prankster who’d been denied entry heckled him from near the entrance.

The total cost of the party was $1,000, its price having been litigated in bankruptcy court; the beer and wine ran out even before Nick had taken the floor. At some point, Emma, now the editor-in-chief of Jezebel, slipped away to pick up some cases of beer, and some of us made our way to the third floor to sit on winding couches and rolling office chairs. Two onetime Gawker writers undertook a shotgun race with cans of Budweiser; some developers played Jenga. Eventually, a few dozen people stumbled out and into cabs for some late, drunk, terrible karaoke. A week later, Nick would call a meeting with the staff of Gawker.com to tell them that the website would be shutting down. But most of them had already heard the news. They’d found out just before, on Twitter.

This article appears in the August 22, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.

This article has been corrected to show that a memo from Nick Denton about Gawker’s shift in coverage went out in November, not October.