In American political campaigns, the correlation between how much attention an issue gets and the actual significance of that issue is rarely strong. In 1996, Bill Clinton campaigned for reelection with a plan for mandatory school uniforms. Four years later, Al Gore’s campaign spent much energy distancing itself from a blow job his boss had received. In 2004, George W. Bush used his reelection bid to highlight the threat gay rights posed to heterosexual marriage.

The financial crisis diminished the frivolous style in American politics for a couple election cycles, but it’s back in full force in 2016: This year’s GOP debates featured roughly as much discussion of Donald Trump’s penis size as they did about climate change, while, in the general election, Hillary Clinton’s IT management habits have seen more coverage than the threat monopolies pose to economic growth.

Still, even considering our political culture’s affinity for the trivial, it’s sort of weird how little our presidential candidates have talked about the impending robot-induced unemployment crisis.

This month, Uber brought its first fleet of self-driving cars to Pittsburgh. Lyft responded by releasing a five-year plan that promises more than half of the ride-sharing service’s vehicles will be driven by robots in 2022.

Lyft’s goal is ambitious, but it’s not insane. Morgan Stanley expects that the technology for fully autonomous vehicles will be in place by 2022, and that human-driven vehicles will be an anachronism two decades later. That’s in line with the projections of Navigent research, which predicts that “by 2035, sales of autonomous vehicles will reach 95.4 million annually, representing 75 percent of all light-duty vehicle sales.”

This is a big deal. Right now, 180,000 Americans work as taxi drivers, 500,000 drive school buses, and 160,000 pilot transit buses, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Another 160,000 work for Uber.

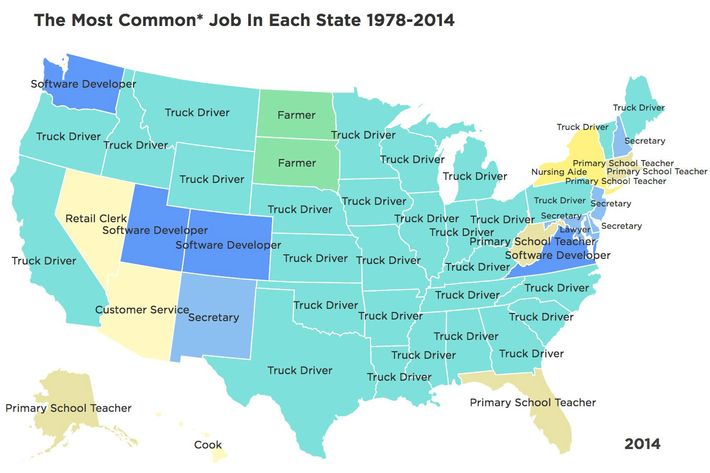

And then, there’s the trucking industry. There’s been a lot of talk over the past year about how trade deals have harmed non-college-educated workers. And that’s a worthy subject of political debate. But it’s also worth noting that one of the few remaining sources of middle-class, blue-collar work is about to be eliminated.

The Labor Department puts the number of truck drivers in America at roughly 2.4 million. The American Trucker Association puts that figure at 3.5 million. Those truckers are central to economies across America’s towns and freeways: Robots don’t buy rooms and slices of pie from roadside motels. Nor do they use their wages to make down payments on new houses for their families. Disrupt the trucking profession and you disrupt a large swath of the American economy.

And the robo-truckers are already here.

The obstacles to fully automated trucking are more legal than technological. Self-driving trucks should arrive long before self-driving cars, as Scott Santens explains:

Any realistic time horizon for self-driving trucks needs to look at horizons for cars and shift those even further towards the present. Trucks only need to be self-driven on highways. They do not need warehouse-to-store autonomy to be disruptive. City-to-city is sufficient. At the same time, trucks are almost entirely corporate driven. There are market forces above and beyond private cars operating for trucks. If there are savings to be found in eliminating truckers from drivers seats, which there are, these savings will be sought. It’s actually really easy to find these savings right now.

These are all, potentially, positive developments. Human beings did not evolve to safely commandeer heavy, high-speed vehicles. People-driven trucks killed 3,600 people in 2014. More than 38,000 people died on American roadways in 2015. In a world of universal driverless cars, McKinsey & Company predicts that crash rates would fall by up to 90 percent.

But as Joel Lee notes in MUO, this wonderful public-safety development would present its own economic challenges: 445,000 Americans work in auto-repair shops, which are (hopefully) about to see a lot less business.

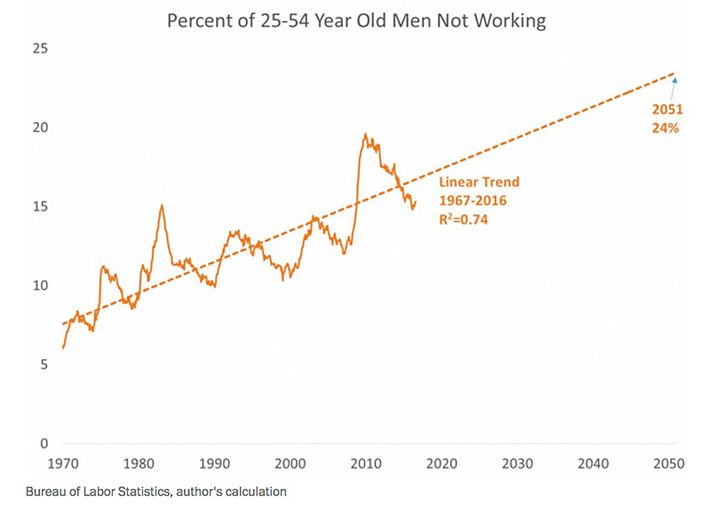

Even if one believed that presidential candidates should focus entirely on problems manifest in the present, robot-induced unemployment would merit a place in the conversation. As Larry Summers argues in the Washington Post, “Job destruction caused by technology is not a futuristic concern. It is something we have been living with for two generations.”

As automation has become more prevalent over the past four decades, working-age men have been dropping out of the labor force. A linear continuation of the trend would put one-quarter of such men out of work by mid-century. And Summers thinks that’s a low-ball estimate. Maybe the answer to this challenge is a federal jobs program — or maybe it’s legal weed, a universal basic income, and widely available virtual-reality headsets.

Regardless, robots are poised to displace more American workers than any of the trade deals Trump decries. Surely, that merits at least as much discussion as Hillary Clinton’s email server.