North Brother Island is a 20-acre speck off the Bronx in the East River. It opened, in the 1880s, as a quarantine site, where the city shipped and shut away the sick. The hospital converted to a drug rehab center for heroin-addicted teens in the 1950s. Corruption and high costs ended the program a little more than a decade later, around 1963. The patients, the staff — everyone — left. The island has been abandoned since.

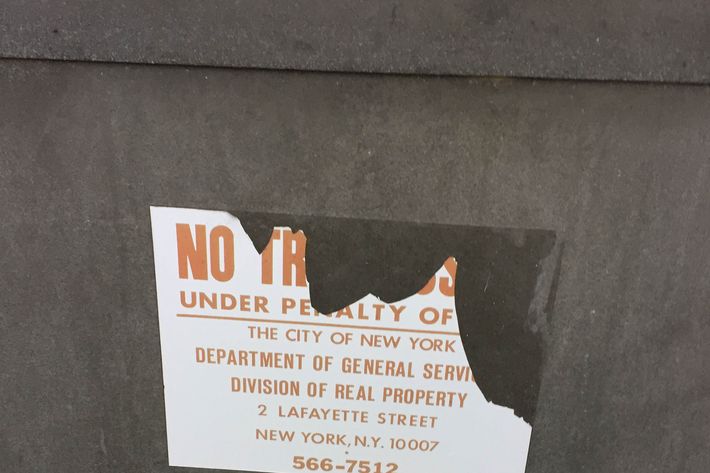

Isolated and uninhabited, North Brother’s campus crumbled — New York’s own lost civilization. The elements cracked opened dormitories and hospital buildings. The roads and paths wore away and were swallowed up by weeds. That transformation has turned an unwanted island, now technically off-limits, into the opposite. Only a few privileged people who have gotten permission from the New York City Parks Department — the island has been under its control since 2001 and is now designated as a bird sanctuary — or lawbreaking urban explorers have visited the ruins.

But that may change soon: City Council members are proposing a way for New Yorkers to take legal trips to North Brother Island. “I think the time has come for a plan to open up limited access,” said councilmember Mark Levine, after a rare visit to Norther Brother Island recently. He and fellow councilmembers, including Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverto, Parks employees, and community members loaded up in motor boats — or, in some cases, a raft with a motor attached — for a tour of the abandoned site.

Levine, who chairs the Parks Committee, first floated the idea of opening North Brother after a visit in 2014. But the island’s biggest draw — its arresting deterioration — is also its big problem: More than half a century of neglect has left North Brother with many hazards. The island’s structures, most of which date back to the late 19th or early-20th centuries, are actively “shedding bricks,” warned John Krawchuk, the executive director of the Historic House Trust, during the tour. He pointed to the chipped smokestack of the old boiler house. Staring up and on the lookout for falling debris means ignoring the dangers below. Off the path, gaping manholes and broken branches are hidden like booby traps by untamed weeds. The poison ivy is inevitable, even on the sanctioned routes.

There’s no easy way to just turn the island into a park. But the City Council has started to tackle that challenge, commissioning a study by the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design to help find ways to make the island more accessible. “We’re not talking about creating the next Governor’s Island with people running around at will,” Levine said. “This is a way for groups of students and people who care about the history of the city to experience in person something that you just can’t read about. It’s not the same to look at pictures, you have to walk on the island to feel the enchantment.”

The enchantment also comes at a price. Any plan to open up North Brother Island is most definitely going to be costly. The island needs a usable dock to receive visitors: To get to the island last week, each member of the group had to clamber up splintering wooden pylons and hoist themselves onto what was once a service dock. Even worse: Rushing to depart before the tide went out, crouching on the dock’s beams and sliding down, feet first, fumbling for the floor of the boat.

“To restore it, maintain it, and manage it — it would be an very expensive undertaking,” NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver said after exploring the island for the first time. “But,” he added, “it is tempting.”

So tempting. The island “essentially served as its own city,” Krawchuk explains. At different points in its existence, it had a functioning morgue, a public school, even tennis courts. As a quarantine, the buildings housed patients, mostly poor and immigrant, with yellow fever and measles and tuberculosis. Some doctors, nurses, and their families boarded on the island; others commuted by boat. Typhoid Mary is the institution’s most famous patient; she was quarantined here on and off for 28 years. She died on North Brother in 1938.

The oldest structures date back to 1885 and the most recent is the Tuberculosis Pavilion, a hospital that opened in 1943, just in time to be obsolete. After World War II, North Brother’s buildings were converted to veterans’ housing. Then came its last chapter as an experimental, but ultimately failed, addiction center for teenagers. (It was said to inspire the play Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie?, for which Al Pacino made his Broadway debut.)

The city has tried to figure out what to do with North Brother Island since it emptied in the 1960s. Mayor John Lindsay proposed selling it, Krawchuk said. Mayor Ed Koch wanted to house the homeless there. In the 1990s, the city considered expanding the facilities at Rikers, whose fortress looms off North Brother’s shore.

North Brother has found new purpose as a migration stopover for herons and other wading shorebirds. It’s classified, with its abandoned sibling South Brother Island, as a “Harbor Herons Region,” a protected area for shorebirds to nest. The Parks Department also invests in reforestation projects, ridding the land mass of invasive species and trying to kill the creeping kudzu and poison ivy that are swallowing the decaying structures, and pretty much the entire island.

Those herons have priority over humans right now, and their protection — and other environmental concerns — gets first billing in any future proposal for North Brother. No visitors are allowed during nesting season. It was over at the time of this recent visit, and even knowing this, the island did seem eerily devoid of animal life. It was almost impossibly quiet, except for the interlopers tromping through the brush.

But the island is alive, transforming itself in real time. Our group passed by North Brother’s church, built on the island around 1906. The chapel is made of wood, making it more vulnerable to rot and decay. It was all but gone when the tour passed by — just barbs of wood poking out from the grass. On his previous visit, Levine said, the chapel’s archway was still standing.

Which is why Levine thinks the city has an obligation to find a way for people to visit, and soon. “You shouldn’t have to be a City Council member or a reporter to visit the island,” he said.

Councilman Levine’s office said the UPenn study is being finalized and should arrive in the next two weeks. It will first be presented to the City Council’s Bronx delegation in November, and the Council’s Parks Committee will schedule a hearing in December about North Brother and other restricted spaces like Hart’s Island. The study will sketch out what has to be done to allow trips — the necessities, like building a landing dock and shoring up the structures. It may also include long-term recommendations, such as the possibility of restoring buildings. Again, there are no real plans yet, but past surveys have identified two potential candidates for revival: the male dormitory, which is one of the island’s original structures, and the coal house, which, built in 1904, is in relatively good condition, says Krawchuk.

The Parks Department, which allowed for the study, will consult with the City Council on any of the researchers’ recommendations. It’s unclear if the study will have a budget proposal to take on even the minimal but necessary upgrades. “It if doesn’t, we’ll work with our staff to quickly sketch out a capital plan,” Levine said.

Which is all to say, New Yorkers might be more likely to walk that floating park in the Hudson before they can do so on North Brother. These are just the first and very small steps to opening up an island that no New Yorkers ever wanted to go to – until they no longer could.