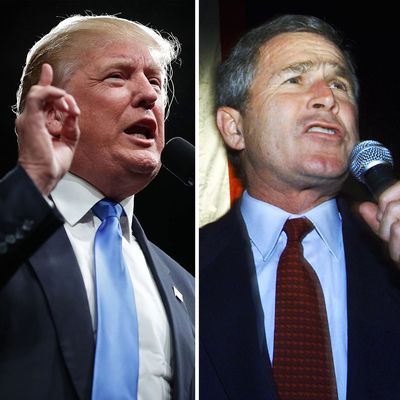

Like George W. Bush 16 years ago, Donald Trump will take office having promised both a larger defense budget and a more-restrained attitude toward the use of military force. Like Bush, Trump seems to be in the process of surrounding himself with national-security advisors much more inclined to shoot and ask questions later.

What could go wrong?

Now, there are large and obvious differences between the 43rd and 45th presidents and their basic orientations toward foreign policy and national security as they entered office. Bush’s plea for greater “humility” in foreign policy during the 2000 campaign was linked to a pretty conventional appreciation of the value of alliances. Trump is apparently more inclined to what acute observers have called a Jacksonian approach to foreign policy: a unilateralist desire to stay out of other countries’ problems, paired with an equally unilateralist determination to use maximum lethal violence if those problems are made ours through aggression or perhaps even provocation. This (in theory at least) should make Trump as commander-in-chief more reluctant than his Republican predecessors to engage militarily in situations that affect less-tangible U.S. interests — much less than those of allies. But the same Jacksonian orientation could lead to the hair-raising use of uncontrolled military action if Trump is convinced he or his country has been attacked, threatened, or perhaps even disrespected.

In Bush’s case, 9/11 turned a “humble” foreign policy into two large and lengthy wars, only one of which really had anything to do with the attacks. With public opinion suddenly and dramatically supporting decisive action to “avenge” the act of terror, it mattered that the president had surrounded himself with advisers still stewing over the inconclusive end of the Persian Gulf War and eager (along with a president still angry at Saddam Hussein’s attempt to assassinate his father) to use the new environment to execute regime change in Baghdad.

Without any doubt, something similar could happen in a Trump administration, even if the game-changing event is less traumatic than 9/11. But the big question is whether the people around him would restrain him, or instead, like Bush’s circle of advisers, use the opportunity to grind their own axes and elevate their own budgetary and policy interests above those of competing domestic influences and priorities.

Trump’s national-security adviser, Michael Flynn, is hardly someone cut out for the role of acting as a voice of restraint, at least when it comes to any kind of threat emanating from a Muslim country. His designated secretary of defense, General Jim Mattis, is a different quantity: a highly respected strategic thinker, as well as an experienced combat leader. But Mattis was also deeply frustrated by the Obama administration’s determination to get out of Iraq quickly and to avoid confrontation with Iran. And he is entirely the product of a military career. Is he going to talk Donald Trump out of military brinkmanship with Iran or a reengagement in Iraq to “kill” ISIS?

It is tempting to say Trump’s choice for secretary of State could be the tiebreaker between fear and hope in calculating the odds things will get crazy if the new president is provoked by some foreign power. John Bolton would obviously feed the perception of a foreign-policy apparatus ready to spring into full-war footing on very short notice. But even the most reassuring figure available, Mitt Romney, spent a goodly portion of the 2012 election warning of Obama’s dangerously weak attitude toward Iran.

And there could an even more immediate test of the impact of personnel on Trump’s diplomacy in the flare-up over the President-elect’s conversation with Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-Wen. Perhaps Trump himself knows little or nothing about the incredibly complex set of protocols that have developed over the years around U.S. relations with Taiwan, but some of the people advising him certainly understand them, and may be trying deliberately to provoke Beijing even before the new administration takes office.

There’s another yet another possibility that has to be taken into account in dealing with a Trump administration: The man really does believe in bluster and intimidation as strategic assets — in business, politics, and, presumably, international affairs. In his mind, it’s all part of the “art of the deal.” So, the people he puts into positions of authority over foreign policy and national security could be symbols as much as actual policymakers. The minute I heard about Mattis’s selection I wondered if Trump really just wanted to be able to tell potential adversaries that his defense secretary was a Marine nicknamed “Mad Dog.”

If that is even half-right, we could be at the mercy of Trump’s Jacksonian instincts when it comes to matters of war and peace. That makes me very afraid.