The bar at the front of the Hunt and Fish Club, the upscale steak-and-martinis joint just off Times Square, has floor-to-ceiling plateglass windows, presumably not so that its customers can have a panoramic view of 44th Street but so that people outside can see what a great time the people inside are having. The restaurant, which bills itself as “the opulent steakhouse that Midtown deserves,” makes a point of saying on its website that it “appeals to both men and women,” and on a night in December, the place was packed with what looked like exaggerated caricatures of both genders. Women in high heels curled unseasonably bare arms around stout, red-faced men in suits, all of them looking as tight and shiny as unopened Christmas presents. Frank Sinatra was booming about New York over the sound system, and the scene had a festive, anticipatory quality, which one got the sense had as much to do with the results of the recent election as with the impending holidays.

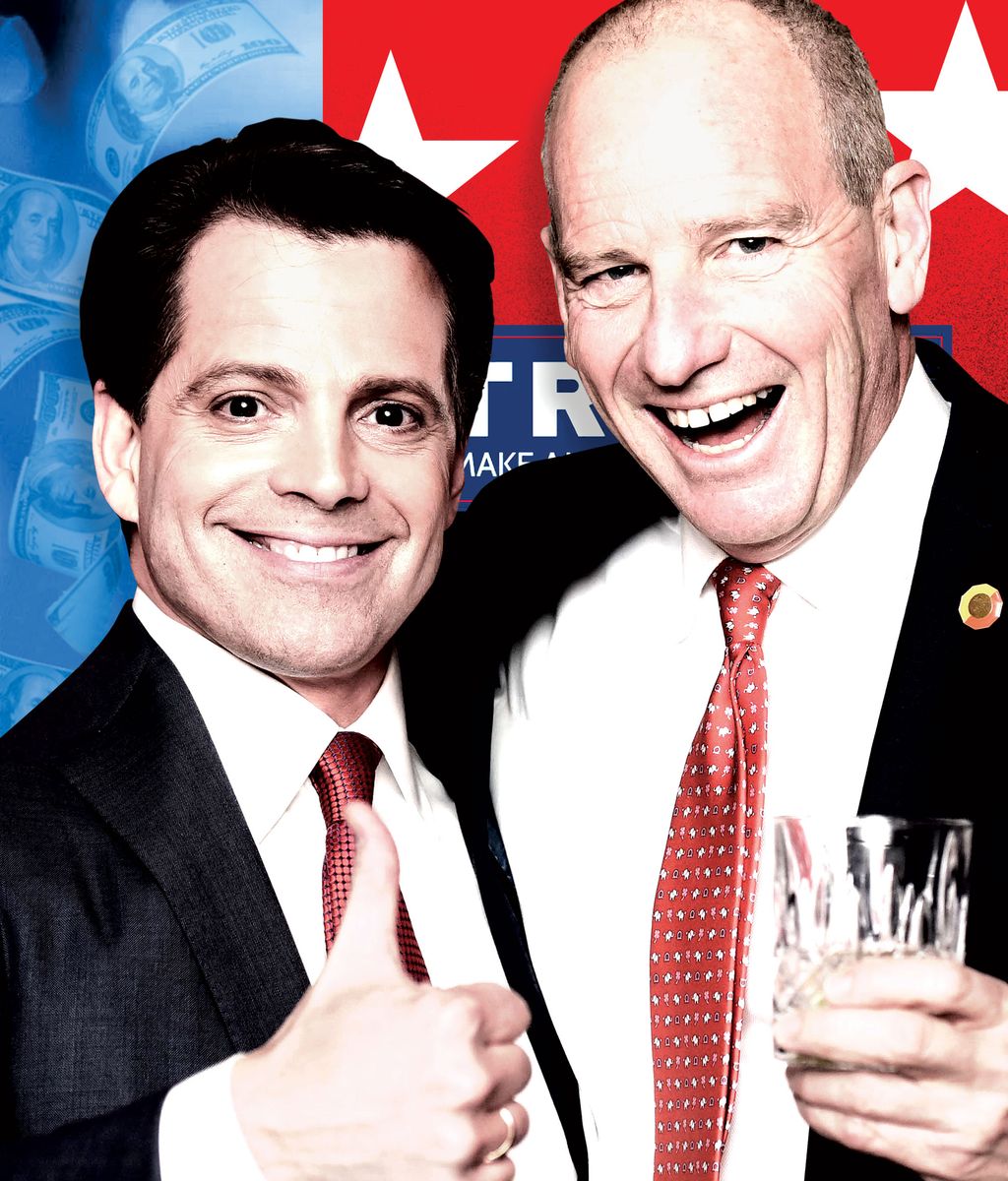

“It’s been great, everybody’s kissing Anthony’s ass now because of Trump,” Nelson Braff, one of the restaurant’s owners, told a table of customers back in the mirrored dining room.

He was talking about Anthony Scaramucci, one of his partners in the restaurant. A money manager and business-news talking head, Scaramucci has been a fixture in New York finance circles since 2010, when he stood up at a town-hall meeting and asked President Obama, “When are we going to stop whacking at the Wall Street piñata?” With his Harvard Law School education and Long Island accent, the Mooch, as he is affectionately called, is known more for his charismatic personality and relentless self-promotion than the middling performance of his company, SkyBridge Capital, a “fund of funds,” which invests in other hedge funds for a fee. His unflagging need to charm every single person he comes into contact with has given him many fans, and his SALT Conference, an annual schmoozefest he hosts in Las Vegas, reliably attracts a Who’s Who of Wall Street, entertainment, and politics, people who find themselves mingling confusedly under salamis and other décor inspired by Scaramucci’s Italian-American heritage. But though he is well liked, the Mooch, like the Fonz, has never been taken particularly seriously. Certainly, few took it seriously when he signed on to Donald Trump’s economic-advisory council last May, since the Mooch, lately off the campaigns of Scott Walker and Jeb Bush, had recently called Trump a “hack politician.” But Scaramucci took to the campaign’s talking points like a duck to water, seamlessly mixing the campaign’s cherry-picked statistics with vignettes from his childhood in Port Washington and impressing the campaign with his ability to do things like somehow make a Department of Labor rule that requires financial advisers to work in the best interests of the people whose money they are investing sound like the primary cause for the decimation of the middle class. “The Department of Labor under Secretary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren wants to put the financial-service advisers basically out of business,” he told a crowd at an event in October, moving along to unrelated facts about lower economic growth and the plight of blue-collar workers as though it were all very closely connected. “So the life that I had as a kid, with the Schwinn bicycles and the Sears Toughskins and the air conditioners going in and out of the windows, that is not happening,” he finished.

When, to everyone’s disbelief, Donald Trump actually won the presidency and became someone to take seriously, so did Scaramucci. Since the election, Mooch’s stock has been way up: Yahoo Finance named him its “Wall Streeter of the Year,” despite the fact that his flagship fund had been performing poorly over the past two years. He has been a constant presence at Trump Tower, squiring bigwigs to meetings with the president-in-waiting. When I found him mixing a margarita for himself in an empty bar downstairs at the Hunt and Fish Club, his face still waxen with makeup after a day on TV, he told me it’s about to go even higher.

“Scaramucci, Exploring Government Post, Weighs Sale of SkyBridge,” he said triumphantly, reading a headline from Bloomberg off his iPhone. Then he launched into a sequence of stories about the first time he saw The Godfather (he was 8) and his uncle Orlando’s Perry Como impression, before returning to the subject of his new position.

“So I said to Vice-President Pence, who was here tonight,” he went on, “I said, ‘I’ll do whatever the hell you guys want.’ I know you probably think that’s, like, me being passive-aggressive,” he said to me, “but it’s not, it’s me being even-keeled. My best service to him is acting as a fair broker for the situation, because what happens in Washington is they will stab you right in the chest with a smile on their face. It’s like the Game of Thrones and the Hunger Games screenwriters got together with the writers of House of Cards and they made a story. And the other thing I have learned about these people in Washington, Nelson,” he said, turning to his partner, who had settled in at the bar, “is they have no money. So what happens when they have no fucking money is they fight about what seat they are in and what the title is. Fucking congressmen act like that. They are fucking jackasses. Do you know how many congressional liaisons we are going to have? I don’t either, but I told Pence, it should be four times whatever Obama had. I don’t know how many he had, but I’m telling you that didn’t work out. I’m telling him if you want to decrease the government, you gotta increase it in certain ways. Pence was great, right, you met him, Nelson, he was great.”

He suddenly stopped and squinted at me. “How old are you?” he asked. “You look good. No lines on your face. What are you, a Sagittarius?”

I told him I’m a Leo.

Scaramucci nodded approvingly. “Fucking king of the jungle!” he said, lifting his drink.

It is not strictly true that there is no money in Congress. But there’s going to be a lot more in Washington now. Despite Candidate Trump’s jeremiads about hedge funds “getting away with murder,” during the transition the president-elect stacked his administration with a murderers’ row of financiers, mostly loyalists and donors who, like Scaramucci, saw in the improbable candidate the opportunity for the deal of a lifetime.

“It’s a classic contrarian bet,” said James Grant, the bow-tied conservative behind the classic contrarian-investing newsletter Grant’s Interest Rate Observer. “Hillary was collecting all this money from all these people on Wall Street. What were your chances of getting into that?” Comparatively, Trump looked like “a low-risk, high-reward political entity.”

“The early bulls on Donald Trump, they saw two things,” Grant went on. “One, there was something there, and it was something that not a lot of people were seeing. When I looked at Donald Trump, I saw the man I knew from the late ’80s, somebody without a sense of proportion, a braggart, a really lousy CEO. But they saw it differently. They saw the value proposition. They saw the risk-reward ratio.”

For the amount of money that a heavy-hitting donor might spend for a couple of lunches with Hillary Clinton and 50 other people, went this reasoning, a Trump supporter could have a ringside seat. Sure, they might lose — they would probably lose. But for billionaires like Robert Mercer, the founder of secretive algorithm-only hedge fund Renaissance Technologies, and Steven Feinberg, the mustachioed gun-rights activist behind Cerberus Capital Management, and housing-market short-seller John Paulson and Gawker slayer Peter Thiel, “the amount of money was trifling. A lot of them lose a lot more than that in a bad day at the market.”

It would at least be an interesting show. “The downside is being associated with a losing candidate,” said Grant. “But they thought, Well, I was with Mitt Romney, so what’s the diff? The upside is being one of a tiny band of visionaries, contrarians, bloody-minded Trumpites — whatever the moniker is going to be — who saw what others didn’t see, and to have a voice, somewhat of an entrée, to influence the policies of the greatest country on the face of the Earth. The risk-reward proposition must have been almost irresistible.”

Obviously, it wasn’t irresistible for everyone. Despite its image as a lair of fat cats, Wall Street has a culture that has, in recent years, tilted Democratic, in part because the party shares with finance a faith in the technocratic future. But also because as banks and other financial institutions have gotten larger, they have also gotten more socially progressive, engineering outreach programs to minorities and women and the LGBTQ community. To be a big-deal person at a major Wall Street firm and publicly align oneself with a candidate who calls for the building of walls and the rounding up of immigrants, a notorious womanizer who slut-shames beauty-pageant contestants and once joked about dating his own daughter, would take what the genteel Grant called “a certain kind of moral courage.”

Or, in the more common parlance of the industry: “Balls.” Which is why the Wall Street denizens Trump attracted — who are now being appointed to various positions of influence and power — are on the whole mostly outliers, established iconoclasts with enormous appetites for risk, a huge amount of fuck-everyone money, and the nihilistic confidence to not only stare into the abyss but to let off a wild, Roarkian cackle while doing so. “A value person is someone who revels in adversity,” pointed out Grant. “Because adversity constitutes the backdrop for value.”

Wilbur Ross saw it. Trump’s nominee to lead the Commerce Department, he had made billions investing in distressed companies and has an estimated $150 million collection of mostly Surrealist art because, as he once told a newspaper, he likes things that are “a little bit strange, a little bit skewed or out of order.” Seeing value in what others dismiss as garbage, liking something even though it hurts your brain a little, that was his thing.

Then there’s Carl Icahn, the legendary corporate raider said to be one model for Gordon Gekko, who loves nothing more than a deal — literally, according to Mark Stevens, who spent two years with him reporting King Icahn: The Biography of a Renegade Capitalist. “He doesn’t love anyone,” Stevens told me, which is a weirdly specific charge to make about a person, made weirder by the fact that he wasn’t the only one to say the exact same thing to me about Icahn. “He doesn’t love people,” he went on. “I have never heard him talk once about America or about capitalism. He only loves deals.”

Which sounds … familiar. Icahn and Ross go way back when it comes to investing in the undervalued entity that was Donald Trump: Both vulture investors found themselves circling him at the same time back in the ’90s, after Trump’s Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City missed a payment to bondholders. “We could have foreclosed and he would have been gone,” Ross told the New York Post last year. But Trump was apparently so winning, in his blustering, blond, inarticulate way, and was such a weirdly popular figure among the people of Atlantic City — “Even then, they were cheering him,” Icahn told the Post — they decided to make a deal with him instead, one that gave bondholders (including Icahn) 50 percent ownership of the casino but allowed Trump to remain the face of it.

This is not to say Icahn necessarily respects Trump: “There’s nobody that Carl likes to imitate more and make fun of more, in a gentle way, than Donald Trump,” Stevens said. “He used to tell me, in his inimitable way, ‘I can’t talk to him in his helicopter. I have to push all the big tits away just so I can see his face.”

But backing that man for president of the United States? That’s a deal that could really pay off for Icahn, and it seems it will, especially now that Trump has named the notoriously combative and allegedly heartless investor (and notorious anti-regulation agitator) his special adviser on regulatory reform, which means that he will have a hand in guiding the actions of the SEC and the EPA, entities that Icahn, who is worth in the neighborhood of $17 billion, has accused of “strangling” his companies’ profits with their “unbelievable” regulations.

“There’s going to be battles on every front,” predicted Stevens, who had little doubt as to who would end up the victor. “Do you know what a Rhodesian Ridgeback is? They like to jump on the backs of lions, and rip their throats out. That’s Carl. Almost universally they give in, he wins.”

To recap: Does Carl Icahn give a flying fuck about Grab ’Em by the Pussy? No, he does not. “These guys don’t care about the social stuff at all,” a female acquaintance of Ross told me tiredly. “They don’t even think about it.”

Last month, I asked John Paulson, who helped throw a $50,000-a-head dinner for Trump at Le Cirque this past summer, about the then-president-elect’s recent tweeting. “Unbalanced?” he repeated. “I don’t think he’s doing anything unbalanced,” he said. “I would say his goals are you know, economic goals, less government regulation and increased prosperity,” he added smoothly before excusing himself, saying he needed to find his wife, who was clearly not there. So far, Trump as an investment is working out pretty good for Paulson, too. His company hasn’t had a big score since 2008, when it made billions off buying mortgage-backed securities. Over the last several years, it has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars unsuccessfully lobbying for the Treasury to revert profits from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which have been going to pay off the bailout, back to shareholders, of which Paulson & Co. is a big one. Now shares in the company have doubled on the expectations that Trump — who happens to be a Paulson & Co. client (there are lots of tentacles in the swamp) — will do just that.

The motivations of Steven Mnuchin, the incoming secretary of the Treasury, are less transparent. More than one financier I spoke to referred to him as a “cipher.” Mnuchin started out on the straight and narrow at Goldman Sachs, where his father, Robert Mnuchin, was a legendary trader, but Steven’s appetite for risk apparently exceeded the boundaries of the firm. After the company went public, he left to start his own hedge fund and, at the rock bottom of the 2008 financial crisis, put together a consortium to scoop up the failing California lender IndyMac Bancorp, which was rebranded as OneWest Bank and sold for $3.4 billion in 2015. A partnership producing movies with Ryan Kavanaugh, the charismatic head of Relativity Media, flamed out in accusations of fraud and eventual bankruptcy, but Mnuchin made it out okay, funneling $50 million from Relativity to OneWest on his way out the door and leaving town with a new wife — an actress 20 years younger. Still, he must have felt something was missing, because when Trump, with whom he’d been involved in an investment deal years earlier, sent him a last-minute invite to his victory party after winning the New York primary, Mnuchin showed up and was convinced enough by what he saw to go all-in. He signed on, the very next day, to be Trump’s national finance chairman, shocking his liberal Hollywood friends and also, it seems, his father, who donated $2,700 to Hillary Clinton. (“I love my son and I’m proud of him and I will leave it at that,” Robert told me. “It’s his world, and I’m not a part of it.”) But the younger Mnuchin made his quite-mercenary goals clear to Businessweek last summer: “Nobody’s going to be like, ‘Well, why did he do this?’ if I end up in the administration.” Why not take a gamble when it could mean having your name printed on actual money?

Scaramucci came onboard a month later, in May. In a lot of ways, he didn’t fit the profile of the bloody-minded Trumpites. “He’s a momentum guy,” said Grant. “He saw it was working and he hopped on.” Though at the time he told Vanity Fair that Trump was not “my first choice or my second choice,” the Mooch warmed to his role, insisting then and now that Trump is secretly a measured and thoughtful individual whose disregard for large segments of the population he governs is merely an act aimed at serving those who elected him. “He knows what his base is,” he said back at the Hunt and Fish Club. “His base is a guy who bought his pants for $7 at the shop. He’s got a pickup truck. He lifted the tires and made a hydraulic whip on the truck, he’s got shotguns in the rack on the truck, and he’s wearing plaid. And he’s in the truck. And he’s having a hard time making his bills. And he’s upset about the global elites who are out there, and he’s like, ‘What are you guys doing?’ ”

Right, the elites.

Back in his office, gentlemanly Grant marveled at the campaign’s ugliness, especially toward the end of the campaign, especially toward Alicia Machado. “All that stuff he said. One horror to the next. But it didn’t matter! If I had been a better analyst of this situation — well, I’m not sure I could have stood it, because I really can’t stand the guy. But you have to admit, it was a pretty good trade.”

Since the election, much of the rest of Wall Street has come around to Trump, thanks to the rising stock market and the ascension of so many of their own. “What he is doing on the business side makes sense,” said Marc Lasry, a longtime Hillary Clinton supporter who will not be taking a role in this administration. “Wilbur will do a good job. He’s made a lot of money, now he wants to serve his country, do something different. Carl is a pure business guy, so he’s going to recommend things that are good for him. Anthony is going to be there explaining things.”

Like others, Lasry had been heartened by the appointment of Gary Cohn, until recently the president at Goldman Sachs, to head the National Economic Council. A Democrat close to Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, Cohn is regarded to be, at the very least, smart, sane, and rational. “Gary’s not going to do anything to screw up his reputation,” said a colleague from his old firm. Although there are aspects of said reputation that make him a good fit for this particular Island of Misfit Toys. A six-foot-three former commodities trader known for being physically and verbally intimidating (Cohn’s signature move was reportedly hiking a leg up on employee’s desk and addressing the person, as the Wall Street blog Dealbreaker memorably called it, on a “Grundle-to-Face Basis”), Cohn was the second-in-command to CEO Lloyd Blankfein, “the Tonto to his Lone Ranger,” as one former Goldman employee put it. Over the years, his frustration with his boss’s refusal to cede him the top spot became well known. “It’s a pretty interesting transition for Gary, because now he can spin it a little bit differently in his own mind,” said the former colleague. “Now he can say it’s more of a ‘call of duty’ thing than ‘I didn’t get the job I wanted.’ ” As news about the work of the Treasury “landing team” has not been particularly encouraging — one official there told me early on the department was asked if it was possible to abolish the Office of Management and Budget — it seems the fate of the world economy may now rest on Cohn’s grundle.

Since the election, the share price of Goldman stock is up 20 percent; this plus the administration’s appointment of at least six figures with the firm on their résumés (among them Scaramucci, who was in his own words “capital-F fired” in 1991, then rehired, and left again in 1996,* and Breitbart Svengali Steve Bannon, who did a stint in the late ’80s) has led to inevitable allegations about “Government Sachs,” but although people at the firm talked up the company’s rich history of public service — former Treasury secretaries from the Clinton and Bush administrations — they made it clear that this set of Goldman alums is not quite like the others. “Look at the cast of characters,” said the Goldman executive. “Gary wanted the big job; he didn’t get it. His relationship with Lloyd was pretty strained at the end. The guys who replaced him he doesn’t get along with. Bannon is a nutcase. Scaramucci was laid off. Mnuchin, he doesn’t have any love for the place; his brother didn’t make partner, he was always in his father’s shadow. None of these people were superstars that someone pulled away. Every one of them was dysfunctional.”

The only person who seems guaranteed to benefit from the Donald Trump administration, everyone seemed to agree, is Donald Trump. “The Trump kleptocracy could be incredible,” said a hedge-fund manager, who, like many others, asked to remain anonymous because he feared retribution from a president who has already displayed a taste for it. “He could turn out at some point to be the wealthiest man in the country from all of this. But I think that all of the people who surround him are going to be disappointed, because Trump is not loyal to anybody but himself.” He pointed to Chris Christie and Mitt Romney, whose heads the president-elect might as well have spiked at the entrance to Trump Tower. “I don’t think you get back with him what you think you are getting.”

For now, at least, the people on the inside seem like they are having a great time. Back at the Hunt and Fish Club, Scaramucci drained his margarita. “Don’t say I was drinking,” he said. A few weeks later, once he is officially appointed to be the Trump administration’s director of the Office of Public Liaison and Intergovernmental Affairs, defending Donald Trump would be his full-time job. And just before the inauguration, he’d be the lone representative from Trump Tower at the World Economic Forum in Davos (where he’d be one of the biggest salamis in a crowd of world leaders and billionaires and would announce the sale of SkyBridge Capital to a Chinese consortium, citing conflicts-of-interest standards).

“What do you really want to do?” he asked me on his way out the door. “You wanna work in the Trump Organization? I’ll bring you up there! Come up to the tower!” He dodged a woman in a fur coat, a dead ringer for Zsa Zsa Gabor, on his way up the stairs. “It will be fucking great!”

Behind him, Nelson Braff stood up from the bar, surveying the room. “This place would do well in Washington,” he said.

*This article appears in the January 23, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been updated to correct the year Anthony Scaramucci was laid off from Goldman Sachs.