President Trump’s approval rating has dropped by about one percentage point per month and now sits in the mid-30s. At the current rate, it would hit zero in September 2020. (A highly unlikely possibility, though with Donald Trump, anything is possible.) Measured in less quantifiable terms, Trump’s political decline has not occurred in so linear a fashion. It has happened, as Ernest Hemingway wrote about bankruptcy, gradually and then suddenly.

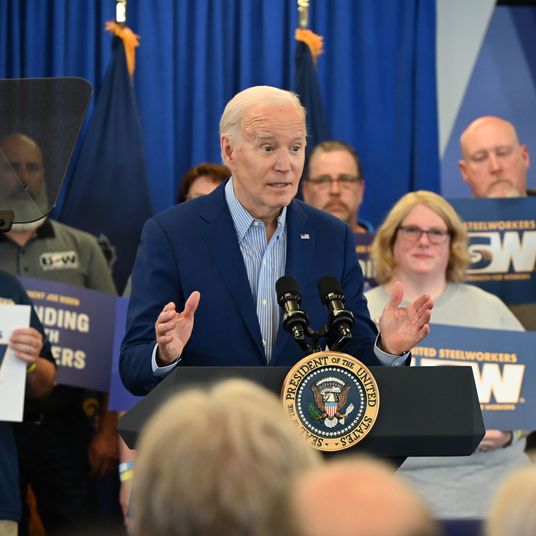

After half a year of comic internal disarray, even in the face of broad public dismay, Trump’s administration had, through most of July, managed to hold together some basic level of partisan cohesion with a still-enthusiastic base and supportive partners in Congress. This has quickly collapsed.

Signs of the disintegration have popped up everywhere. The usual staff turmoil came to a boil in the course of ten days, during which the following occurred: The president denounced his own attorney general in public, the press secretary quit, a new communications director came aboard, the chief of staff was fired, the communications director accused the chief strategist of auto-fellatio in an interview, then he was himself fired. Meanwhile, the secretary of State and national-security adviser were both reported to be eyeing the exits. (Against this colorful backdrop, the ominous news that Robert Mueller had convened a grand jury barely registered.)

More disturbingly for Trump, Republicans in Congress have openly broken ranks. When the Senate voted down the latest (and weakest) proposal to repeal Obamacare, Trump demanded the chamber resume the effort, as he has before. This time, Republican leaders defied him and declared the question settled for the year. When the president threatened to withhold promised payments to insurers in retribution, Republicans in Congress proposed to continue making them. Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Charles Grassley, responding to the president’s threat to sack Jeff Sessions, announced he had no time to confirm a new attorney general. Many Republican senators have endorsed bills to block the president from firing the special counsel.

The most humiliating rebuke came in the form of a bill to lock in sanctions on Russia, passed by Congress without the president’s consent. The premise of the sanctions law is that Congress cannot trust the president to safeguard the national interest, treating him as a potential Russian dupe. It passed through both chambers almost unanimously. Trump delayed signing the bill for days, then submitted to its passage in the most begrudging fashion possible, releasing a statement that reads less like something a president would publish to commemorate the signing of a law than a petulant handwritten note a grounded teen might tape to the bedroom door. “Congress could not even negotiate a health-care bill after seven years of talking,” wrote the president of the United States. “I built a truly great company worth many billions of dollars. That is a big part of the reason I was elected.”

During his very brief tenure as communications director, Anthony Scaramucci blurted out something very telling: “There are people inside the administration that think it is their job to save America from this president.” The conviction that Trump is dangerously unfit to hold office is indeed shared widely within his own administration. Leaked accounts consistently depict the president as unable to read briefing materials written at an adult level, easily angered, prone to manipulation through flattery, subject to change his mind frequently to agree with whomever he spoke with last, and consumed with the superficiality of cable television. In the early days of the administration, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and then–Homeland Security Director John Kelly secretly agreed that one of the two should remain in the country at all times “to keep tabs on the orders rapidly emerging from the White House,” the Associated Press reported recently.

And the insurrection appears to be creeping outward. When Trump tweeted that he would ban transgender Americans from military service, the Defense Department announced there had been “no modifications to the current policy” and that, “in the meantime, we will continue to treat all of our personnel with respect.” When Trump gave a speech to police urging them to rough up suspects, several police chiefs and even the head of his own Drug Enforcement Agency registered their public objections. The accretion of these acts of defiance is significant. The federal government has flipped on its chief executive.

Barring resignation or removal from office — which would require the vote of a House majority plus two-thirds of the Senate — we are stuck with a delegitimized president serving out the remaining seven-eighths of his term. Politically gridlocked presidencies have become normal, but for the office to be occupied by a man whose own party elites doubt his functional competence and even loyalty is, to borrow a term, unpresidented. Trump’s obsession with humiliation and dominance has left him ill-prepared to cope with high-profile failure. He seems unlikely to content himself with quiet, incremental bureaucratic reform.

And yet it is difficult to see what Trump can do to reverse the situation. His next major domestic-agenda item, a regressive tax cut, is highly unpopular. He has inherited peace and prosperity. Nobody in the administration has been indicted. It is far easier to imagine conditions changing for the worse than the better.

There is one frightening exception. Trump could regain public standing through the rally-round-the-flag effect that usually occurs following a domestic attack or at the outset of a war. A miniature version of that dynamic was on display in April, when Trump launched a small missile strike on Syria, garnering widespread praise in the media for his newfound stature. The 9/11 attacks elevated George W. Bush’s approval ratings for three years, long enough for his party to gain seats in the 2002 midterms and for Bush, two years later, to win what is still the Republican Party’s only national-vote plurality victory since 1988.

Trump’s authoritarian tendencies make the prospect of his rebuilding his legitimacy on the basis of security especially dangerous. The number of Republicans who see Trump as a strong leader has dropped by 22 percentage points since January. Trump’s opportunity lies in exploiting fear to demonstrate strength.

There is an answer to this danger. It is to not simply assume Trump can — or should be allowed to — use war or terrorism to his advantage.

After 9/11, Democrats and the mainstream news media, harking back to the national unity that prevailed after Pearl Harbor, demonstrated their patriotism by supporting their president almost unquestioningly. That choice allowed Bush to escape scrutiny for policies that may have helped enable the attacks to happen. (Before, his administration had deemphasized the fight against Al Qaeda.) Bush’s ground-zero halo gave him a presumption of competence as commander-in-chief that enabled him to launch a war without planning for the occupation. It mostly survived the revelations of the 9/11 Commission Report three years later and did not fully dissipate until the Iraq War occupation had unmistakably descended into a quagmire.

The ability of a president to gain popularity by launching (or suffering) an attack is not a law of nature. It reflects, in part, choices — by the opposition to withhold criticism and by the news media to accept the administration’s framing of the facts at face value. A chaotic, still-understaffed administration led by a novice commander-in-chief who has alienated American allies deserves no benefit of the doubt. Everything from Trump’s incompetent management of the Department of Energy, which safeguards nuclear materials, to the now-skeletal State Department, to his blustering international profile has exposed the country to an elevated risk of a mass tragedy. A long-term task of the opposition is to prevent the crumbling presidency from transmuting that weakness into strength.

*This article appears in the August 7, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.