In March 2016, Marco Rubio stood before the conservative movement’s largest annual gathering — and implored his audience to remember what it believed.

“Being a conservative can never be about simply an attitude,” the Florida senator explained. “Being a conservative cannot simply be about how long you’re willing to scream, how angry you’re willing to be, or how many names you’re willing to call people.” Instead, Rubio insisted, that being a conservative was about remaining faithful to “a set of ideas and principles” — including free enterprise, traditional values, and the inviolability of Constitutional rights.

Within weeks, Rubio’s audience would prove him wrong.

To win the Republican nomination, Donald Trump did not need to demonstrate a commitment to free-market principles, traditional sexual morality, reverence for the Constitution, or even respect for American prisoners of war. He just needed to be better at mocking the size of Little Marco’s torso than Rubio was at mocking the size of his hands — while speaking to the GOP base’s anxieties about immigration and demographic change in terms more lurid, and with proposals more draconian, than his rivals could countenance.

We’re about to find out which of these two elements of Trump’s appeal was more fundamental to his success. Did Rubio err in presuming that conservatism was about more than just an attitude — or in failing to include a single word about immigration in his paean to conservative principles?

On Wednesday night, the president reached a tentative agreement with Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi to trade some form of legal status for the 800,000 “Dreamers” — undocumented immigrants who were brought to this country as children (and grew up to be gainfully employed and bereft of a criminal record) — for unspecified border-security measures. The White House quickly denied that any such deal had been made. Trump reiterated this point early Thursday morning, insisting that he would never show mercy to the Dreamers unless Democrats agreed to “massive” border-security measures.

But, moments later, the president suggested that he saw amnesty for Dreamers less as a point of leverage over Schumer, than as a positive good, in itself.

Throughout last year’s primary — as Establishment conservatives watched their movement choose a xenophobic insult comic over the tenets of Reaganism — the nativist right lapped up their tears. The intellectual bankruptcy of globalist “cuckservatism” had been exposed: The nationalist populist message had proven to be so powerful, a political neophyte could ride it to the summit of the Republican Party.

But now, it’s Breitbart’s turn to anxiously remind its followers of what conservatism is and is not. On Thursday morning, Steve Bannon splashed “Amnesty Don” across his homepage; every nativist’s favorite congressman, Steve King, warned that if the deal were real, Trump’s base was “blown up, destroyed, irreparable, and disillusioned beyond repair”; Laura Ingraham asked when the native-born Americans who’ve been victimized by mass immigration will get their amnesty; Ann Coulter called for the president’s impeachment.

The nationalist right’s message, in sum: Trumpism can never simply be about an attitude — it’s built on a set of ideas and principles.

There’s reason to believe that Breitbart’s right about this — but there’s also cause for thinking that they may end up suffering the same disillusionment that the National Review did in 2016.

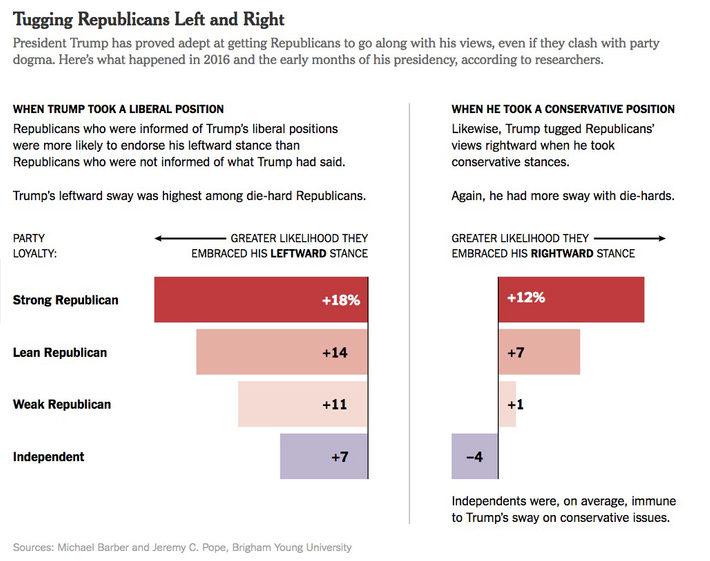

In the New York Times, Thomas Edsall assembles evidence for the latter scenario. Edsall highlights a recent study from two political scientists at Brigham Young University, which found that many Republican voters are “malleable to the point of innocence, and self-reported expressions of ideological fealty are quickly abandoned for policies that — once endorsed by a well-known party leader — run contrary to that expressed ideology.”

Trump’s singular affinity for cycling through contradictory policy commitments aided the researchers’ work: By citing opposing positions that the mogul had taken on a series of issues, they could test the GOP electorate’s willingness to follow their standard-bearer left and right. As Edsall explains:

The authors conducted a survey with YouGov of 1,300 voters broken into five subgroups, each of which was asked 10 questions using a research design that employed “both ‘conservative’ and ‘liberal’ Trump cues.”

1. “Do you support or oppose increasing the minimum wage to over $10 an hour?”

2. “Donald Trump has said that he supports this policy. How about you? Do you support or oppose increasing the minimum wage to over $10 an hour?”

3. “Donald Trump has said that he opposes this policy. How about you? Do you support or oppose increasing the minimum wage to over $10 an hour?”

The result: The more strongly a voter identified with the Republican Party, the more likely she was to follow Trump leftward.

Critically, the same held true when voters were asked to identify themselves by ideology rather than by party: Strong conservatives were more likely to embrace a Trump-backed “left-wing” position than those voters who identified as more ideologically moderate.

In other words: It appears that when most voters say they are strong conservatives, they mean that they are strong Republicans — and when they say they are strong Republicans, they mean that they are loyal to the Republican president.

This finding is supported by a large — and growing — body of political science research. Most Americans do not have strong, coherent ideologies — but do have strong group identities, which tie them to one of the two major political parties.

Edsall opens his piece with one stark testament to this fact: In 2011, 61 percent of white Evangelical Christians disagreed with the statement, “an elected official who commits an immoral act in their personal life can still behave ethically and fulfill their duties in their public and professional life,” according to a poll by the Public Religion Research Institute. This made such Evangelicals the single least-forgiving cohort in the institute’s survey.

Five years and one “grab ’em by the pussy” tape later, 72 percent of white Evangelicals told PRRI that an elected official could behave ethically in public life even if he had committed immoral acts in his private one. Now, no other religious group is more tolerant of sexual libertinism in its political leaders than the one that belongs to “the moral majority.”

And yet, those who wish to insist on the ideological character of Trumpism can find some comfort in this finding. After all, our president doesn’t talk the talk of a Christian conservative — or, at least, he doesn’t talk it convincingly. But he does, most definitely, walk the walk. In revising its views on the relationship between private morality and public ethics, the Christian right (arguably) put substance above style. By tolerating Trump’s “locker room talk,” white Evangelicals secured Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, a ban on transgender military service, and the elimination of U.S. funding for international organizations that provide abortions.

Evangelicals didn’t win these gains by dumb luck — they didn’t join Trump’s cult of personality without preconditions. By the time of his coronation, Trump had committed himself to every major item on the Christian right’s agenda — and made one of the movement’s favorite sons his running mate.

A portion of the Republican electorate might have been willing to follow Trump left and right on abortion, transgender rights, and (so-called) religious liberty. But that group never could have elected him without the cooperation of the organized, ideological activists of the Christian right.

One could make the same argument about the Breitbart faithful. Like the conservative Christian movement, the nativist right was dictating terms to the Republican Party long before Trump came on the scene. In recent Republican Senate primaries, the more moderate a GOP incumbent’s positions on immigration, the more likely they were to be ousted by a challenger.

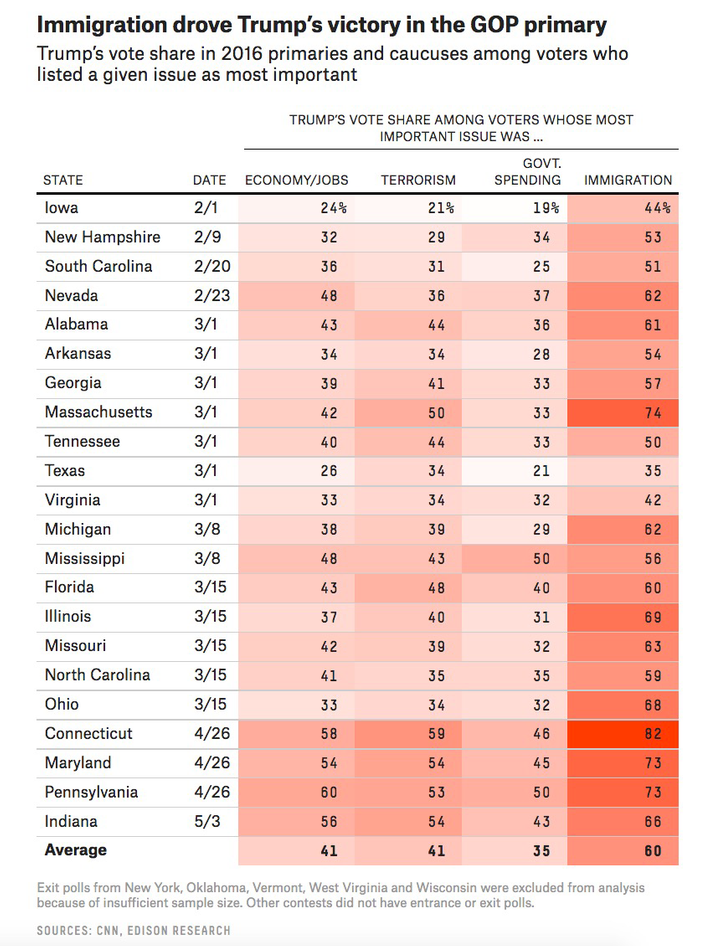

More crucially, Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential primary was powered by his outsize support among Republicans who named immigration as their top issue, as FiveThirtyEight has helpfully documented.

Voters are, generally, animated by identity, not ideology. But some identities are more salient than party affiliation. The 2016 primary was a vivid illustration of this fact: The GOP’s political leadership, elite commentators, and donor class cried out, in unison, that Trump was an interloper — a Clinton donor, a Democrat, a New York liberal. But these appeals to the GOP base’s partisan identity proved far less potent than Trump’s appeals to white racial panic.

It seems likely, then, that Trump needed his hard-line stances on immigration to take over the Republican Party. But it’s an open question whether he needs to toe Breitbart’s line on the issue to retain his grip on the GOP base.

The right’s most highly engaged, anti-immigration activists will sweat the details of Trump’s policies. But it’s not clear that the nativist right’s rank-and-file are so detail-oriented. During the general-election campaign, Trump occasionally zigzagged on the finer points of his immigration platform without ever losing significant Republican support.

For many Breitbart readers, the election of “the first white president” may matter more than the legal status of a select group of undocumented immigrants whom they’ve never actually encountered. Solely by serving as our government’s figurehead, Trump affirms the nationalist right’s conception of American identity. Plus, he still makes the “libs” super mad.

Take the portion of the Breitbart right that cares more about what President Trump stands for than what he does, add the segment of the Republican base that puts fealty to party above any ideological scruple — and Steve Bannon may soon find himself leading a fringe, rump faction no more formidable than the #NeverTrumpers of yesteryear.