New York Magazine all but invented the new-hot-neighborhood feature. In 1969, a cover story by Pete Hamill declared Brooklyn — especially Park Slope — “the sane alternative” to Manhattan living, laying out the template for hundreds of features, columns, and web posts to come. We have never quite stopped helping our readers find a new place to live (or, alas, making them feel anxious about that quest), although the tenor of our coverage has shifted away from the basic idea of pointing out an underpriced and interesting neighborhood, for the simple reason that there’s no such thing anymore.

Instead, we zero in on areas where change is happening rapidly and organically or, in the case of our latest look at Long Island City, rapidly and very much nonorganically. The waterfront district north of Greenpoint and south of Astoria has become a thicket of glass condo towers backed up by a stand of office buildings and finally seems to be catching up to Downtown Brooklyn as a high-rent location.

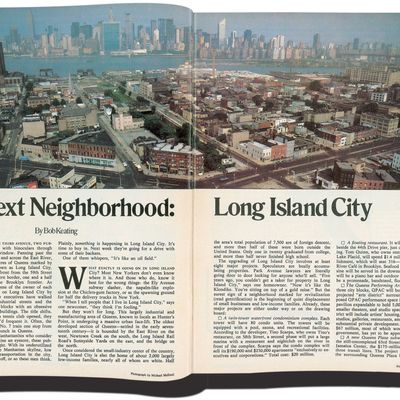

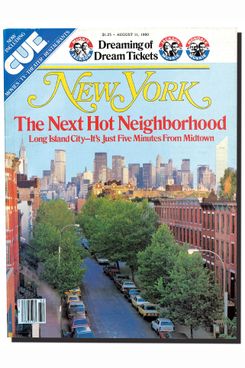

It’s been a long time coming. In 1980, LIC looked very different. Its industrial waterfront and loft spaces were emptying out, and little pockets of residential neighborhood life, around St. Mary’s and in Hunters Point, were not particularly well known. About the only sign of the future in the neighborhood was a new tennis club. Nonetheless, a big feature by Bob Keating went on the cover of New York, gamely declaring it “The Next Hot Neighborhood” and suggesting that those loft spaces were going to be the next Soho. Keating stood with a pair of investors in a Manhattan tower as they peered across the river with binoculars, and what they saw was money. “They know the vacant buildings. The title shifts. What’s new, what’s old. When a tennis club opened, they joined. A new restaurant? They’d frequent it … Plainly, something is happening in Long Island City. It’s time to buy in. Next week they’re going for a drive with some of their backers. One of them whispers, ‘It’s like an oil field.’ ”

What happened in the ensuing 37 years? Why didn’t the oil field supply a gusher right away? Carl Swanson’s story, in the current issue, lays out most of the reasons: The charm of brownstone Brooklyn and the physical accessibility of Williamsburg (just one stop away from the East Village) pulled away people who might have gone to Queens first. Only with a round of rezoning by the Giuliani and Bloomberg administrations in the early aughts did it all start to come together. When Long Island City’s time did come, it happened fast.

After we took our first look at the neighborhood, at least one reader was not having any of it. “Seeing a photograph of my block in Long Island City on the cover of New York Magazine was a most unpleasant surprise. Reading the article was a thoroughly rotten experience,” wrote Joan Schenkar. “It is precisely this sort of article which encourages the ceaseless, immoral displacement of working people (who maintain a neighborhood) and artists (who embellish a neighborhood) by developers (who destroy a neighborhood). I never thought to wish a fellow writer economic woe — but here’s hoping Robert Keating’s landlord triples his rent.”

Schenkar, who wrote plays and later biographies — notably a book about Patricia Highsmith — lived on 45th Avenue. “I’m the daughter of a developer, and I know what happens,” she says today. “I used to ride my bike there — there wasn’t anywhere to shop in Long Island City, so I’d bike over to the next neighborhood.” She rented her apartment from a streetwise guy named Sal Saraceno, who’d taken a shine to the area in the late 1950s (and had been featured in our story). “He’d bought up a great deal of the brownstones on the block,” she says. “I was in the only wooden house — a Queen Anne. We all complained about Sal’s rent, and it was $600 for the whole top floor.” Saraceno was inclined toward preservation rather than demolition, and today that block is the core of the Hunters Point Historic District.

Despite her concerns about development, Schenkar managed to stay for almost another decade. In 1989, she tried to buy her building, but Sal and his partner wouldn’t sell. Instead, she left town for Vermont, keeping a tiny pied-à-terre in Greenwich Village. Today she divides her time between that same Village apartment and another in Paris. “We all love what’s happened to Brooklyn — apart from the prices,” she says. “But you enter Brooklyn now and everything’s in quotation marks. Young people who want a life in the arts can’t afford to live anywhere nearby. I’m just glad it took 30 years to happen in Long Island City.”

*This article appears in the September 4, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.