The Museum of Ice Cream, in San Francisco, is not a museum. Rather, it is a sprawling warren of interactive, vaguely hallucinatory confection-themed exhibits: brightly colored rooms with flattering lighting that contain, among other things, a rock-candy cave, a unicorn, and a swimming pool of rainbow sprinkles, now Instagram-influencer-infamous. It smells like fruit-flavored chemicals. There are seemingly infinite backdrops against which to take a cute selfie. It’s like a haunted house for digital natives; a Willy Wonka–induced fever dream. It’s not a store, though there’s plenty to buy. It’s not an ice-cream joint either, though the treat’s available. It’s an elusive concept with a concrete aesthetic. It is, per its co-founder and creative director, Maryellis Bunn, an Experience.

Bunn is a disarming, blunt, slightly intense 25-year-old; her “ice-cream nickname” — everyone on staff has one — is Scream. She is from Laguna Beach, California, and considers herself an old soul. Fluent in the tech-infused vocabulary of corporate America, she speaks about her business in terms of iteration, beta testing, and key performance indicators (KPIs). Though Bunn denies any talent for social media, her personal brand is on point, with a well-curated Instagram account of aspirational adventures: relaxing at an onsen, swinging in an ocean hammock in the Maldives. She is unnervingly millennial.

Bunn and her business partner, Manish Vora, who previously worked on Wall Street and as CEO of Lightbox, an event space in New York, opened the first Museum of Ice Cream last summer, in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District. As a recent Parsons graduate living in the West Village, Bunn found the city’s existing institutions disappointing: They hadn’t adapted to larger cultural currents, she said, leaving little that would “engage and capture” her demographic. “The old traditional experiences — take museums, for example — are the institutions that become more and more archaic,” she told me. “They just haven’t been able to reformulate for the shifts in what people are interested in.” The duo self-funded the museum, and they settled on ice cream because, she explained, everyone “has an ice-cream story,” and “ice cream was very successful through our last economic downfall.” Thirty thousand tickets, priced between $12 to $18, sold out in under a week.

The San Francisco location is their third. (At least for now, all are pop-ups.) An L.A. MoIC opened this past spring and has been visited — and heavily documented — by the likes of Katy Perry, Kim Kardashian, and Gwyneth Paltrow; on Mother’s Day, Jay-Z, Beyoncé, and Blue Ivy were photographed lounging in the museum’s Sprinkle Pool. “This is just the best place!!!!!!” Drew Barrymore posted on Instagram. There have been Museum of Ice Cream corporate tours, costumed photo shoots, and proposals. In L.A., a couple came to reenact their wedding, dress and all. “We Storied it,” Bunn said, referring to the Instagram feature.

San Francisco’s museum is housed in a landmarked 1910 former bank building — previously occupied by Emporio Armani — that stands right at the heart of Market Street. On a recent afternoon, a family of four, wearing plush birthday hats shaped like upside-down ice-cream cones and procured from Etsy, stood in the line that wrapped around the corner. “I hope you all die from this shit,” howled a man in fatigues as he zipped past on a scooter; the security guard, wearing an earpiece and a pink bow tie, didn’t blink.

Inside, the visitors all looked delighted, gleeful. It was four in the afternoon, and the museum was full of children — a 2-month-old in a HELLO WORLD onesie; kids in ice-cream-themed clothing. Employees of the museum — Bunn refers to them as the Pink Army — wore light-pink jeans and branded T-shirts and hot-pink aprons.

Most of the exhibits were contained in the building’s basement and former vault. Visitors were dispatched in small groups, led by guides who were available for assistance but largely went ignored. Every room featured an interactive component: something to eat, touch, or smell. (One of the rooms has scented wallpaper.) From start to finish, the visit is designed to last for 45 minutes. It’s hard to say what, exactly, that experience is meant to entail.

People seemed excited to witness the space in person, after seeing it online; they were especially enthusiastic about documenting themselves inside of it. From what I could tell, a central experience of the Museum of Ice Cream was one that most visitors would already be familiar with: patiently waiting in line.

Bunn toured me through the space briskly. The first pieces we encountered were her own: gold, ice-cream-related objets (a whipped-cream can, a banana, a scoop) resting on pink pedestals, and large, minimalist paintings that riffed on Neapolitan ice cream. One, a pink canvas with a white stripe, in a matching pink frame, was called Neapolitan Sans Chocolate. “Trademark’s my best friend,” Bunn later told me. “I had to coin everything in this museum as my art pieces … It gives me more opportunity to protect rights on them.” Bunn isn’t the only player in the Instagram-optimized “space”; in San Francisco alone, there is the also-sold-out Color Factory, in which visitors are encouraged to “Lose yourself in 10,000 colored ribbons, sink into a giant yellow ball pit, catch some rainbows, smell colorful memories.”

At MoIC SF, almost all of the rooms featured aggressive shades of pink. The space was detail-oriented — one room held a wall fully covered with pink saltwater taffy, and pink carnival tickets papered the floor — but none of these details was small enough to be noisy or lost in a frame, ensuring that all would translate nicely to a small-screen format. In Marye’s Diner, a sparsely decorated 1950s set piece, the décor was straightforward: neon-pink jukebox, retro stools, and a wall covered in pink records labeled with ice-cream puns (“Scoops! I Did It Again,” by “Britney Pears”).

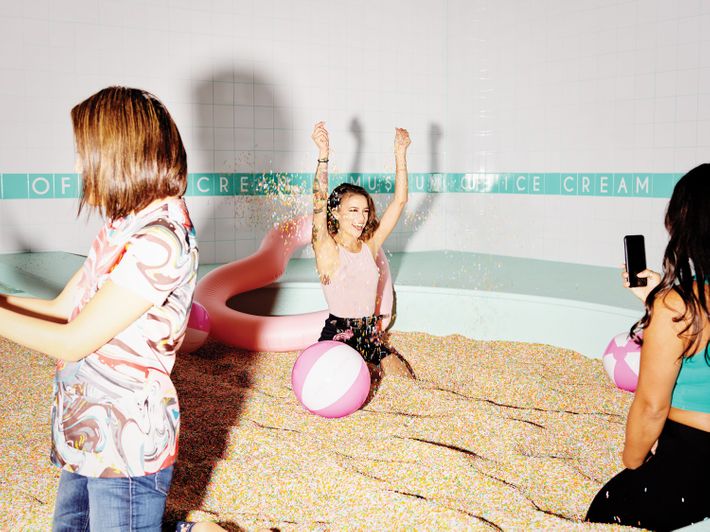

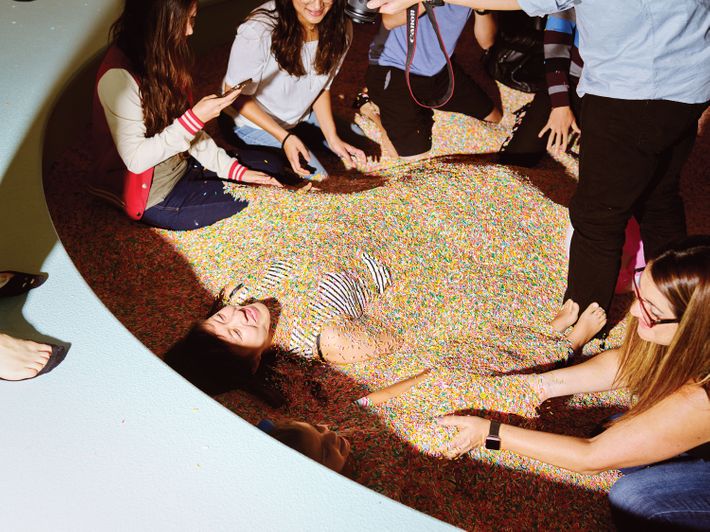

We passed through the “Rainbow” exhibit, “a tribute to San Francisco’s history of acceptance,” which included a pony-size unicorn and a mirrored crawl space in the tradition of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room, then traveled back upstairs to the Sprinkle Pool zone. “Founder and Creative Director, Maryellis Bunn, always dreamed of swimming in an ocean filled with sprinkles,” read the exhibit label. A staff member was busily sweeping errant sprinkles — made of plastic — back into the pool. “You wanna go in the pool?” Bunn asked me flatly. “Shoes off.” She leaned against the wall and checked her phone. I sat on the edge of the pool, and stuck my legs in. It felt a bit foolish; it felt incredible.

We exited the museum through the gift shop — selling pink journals embossed with the word FEMINIST ($10) and “self-love pinky rings” ($149) — and settled in a café across the street. “The most powerful thing for me, and I think the most rewarding also, is just watching the experience,” Bunn said. “I’ll pull up L.A. right now. We can watch it live.” She opened an app on her phone displaying security footage. “You can see where high points of engagement are,” she explained. “I want people to feel safe to explore. Oftentimes we’re so controlled by outside forces and have these ideals that are put on us. If I can create a place that takes off these barriers and propels you to do things, that’s, like, one of my KPIs.”

Bunn’s driving design philosophy is something she calls “social squared.” The aim is to build environments that encourage social interaction between strangers. It’s hard to say whether the museum has been successful on this front: Most people seemed to be moving through the space with family or friends, occasionally turning to strangers to ask for help snapping a photo.

“Ice cream is just a way to get people in the doors and feel safe,” Bunn said. “Then I have the opportunity to do anything.” On a recent visit to Disneyland, she was disheartened to find that the experience was nearly identical to the one she remembered from childhood. “To some, that’s nostalgia,” she said. “But as that goes on for five, six more generations — I’m not sure how successful that’s going to be.” The park didn’t optimize for social engagement, she said. Given the price point, the return on investment was too low, and besides: Millennials don’t have the attention span. “Our generation doesn’t want to spend six hours doing anything,” she said. “I love Disneyland, but it’s just not … it’s not for today.”

The museums were able to get off the ground in part thanks to their strategic partnerships with companies like Tinder, Dove Chocolate, and Fox: In New York, Tinder sponsored an exhibit called “Tinder Land,” which featured a two-person swing shaped like an ice-cream sandwich and a wall-mounted iPad on which visitors could swipe through to “match” with their ideal ice-cream flavor. “Advertising is dead,” Bunn said. “The way in which we are able to have our visitors physically, tangibly, sensually engage with brands has a return on investment that no ad could ever come close to.” Dove, she claimed, saw a 9 percent spike in U.S. sales after distributing chocolate at the L.A. location (Dove specified the sales hike was only for its Promises line). The museum’s brand is now strong enough that Bunn no longer needs to rely on sponsorship in such an explicit way. The San Francisco museum is sponsored by American Express; that company’s branding appeared only sparsely during ticket sales and on a small sign in the gift shop. The ice cream is donated to the museum by local purveyors for brand exposure.

Bunn, who previously consulted independently on design and business strategy for companies like Facebook, and was head of forecasting and innovation at Time Inc., found inspiration for the Museum of Ice Cream in the shifting retail landscape. “I see retail as a dead industry,” she said. “There are billions and billions of acres of retail square footage across America, across the world, that have nothing. No one has a solution for it.” (At last estimate, in 2017, there was about 860 million square feet of available U.S. retail space.) In the future she foresees, retail will move online, to be replaced in the physical world with experiences. She was vague about what, exactly, these would be. The Museum of Ice Cream is not innately entertaining, nor is it especially educational: There is a timeline of ice-cream history, and a few ice-cream facts that seemed sourced from a search engine (“How much money does the ice-cream industry generate?”). The experience was, above all, a novelty, and a place to be both online and off.

A few nights later, the line outside the Museum of Ice Cream was once again around the block. It was 8:30 p.m., post-bedtime, and inside, there was a notable absence of children. The space had a vaguely manic, second-glass-of-wine energy. High-spirited remixes of pop songs — “Party on the West Coast,” by Matoma — thumped through the rooms. Nearly everyone was taking photographs or being photographed. In Marye’s Diner, a Pink Army delegate was warming up the crowd. “Who wants ice cream?” she asked. The group shrieked as if they were going downhill in a SoulCycle class. Around the corner, another member of the Pink Army was spinning cherry cotton candy sprinkled with “fairy dust” (edible glitter). “I’ll make you a tiny one,” she said to me, winking. “It’s really cute for Instagram.” Two women, standing in line for the Sprinkle Pool, scrolled through their phones, looking at geotagged photos of strangers in the Sprinkle Pool.

In the two hours that Bunn and I spent together, she neither laughed nor smiled. When I mentioned this, she was unsurprised. “That’s pretty accurate,” she said. “I’m not what most people would think would be the mind behind this. I’m hyperserious.”

Despite the success of the San Francisco location — tickets sold out immediately, and the museum has already extended its run to mid-February — Bunn rated it a three on a scale of one to 100. In the short term, she hopes to open 180 Museums of Ice Cream, both domestically and internationally. She’s ready to move away from ice cream, at least eventually, to throw her audience some curveballs. Thinking further ahead, she would like to curate and host the inaugural party on Mars. I clarified that she meant actual, literal Mars, not a Mars Experience on Earth. “Oh, no,” she said. “That would be boring. The party would be fun.”

But Bunn’s long game is even more ambitious than going to Mars. When I asked what her ultimate dream was, Bunn looked at me as if it were obvious. “I want to be the next Disney,” she said. “I could take all of those different installations that we just went through, and I could build them out into city blocks. It would be my Heaven. Could you imagine?”

*This article appears in the October 2, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.