Justin Timberlake will perform at the Super Bowl this Sunday for the first time since 2004. The performance marks the end of a 14-year saga for the singer, who first showed up at the 50-yard line back in 2004, and in the most famous non-football incident in Super Bowl history, perpetrated Janet Jackson’s so-called “wardrobe malfunction,” removing a part of Jackson’s wardrobe and exposing her mostly bare breast to an estimated audience of 89 million viewers for nine-sixteenths of a second.

In simpler times, the halcyon days of the early aughts, this caused a major media firestorm. Many theorized that the incident was staged for attention. For the next five years, the Super Bowl halftime show refused to touch modern music with a ten-foot pole, instead featuring baby-boomer acts like the Rolling Stones, the Who, and Bruce Springsteen. The closest any of these shows came to risqué was Prince pretending that his guitar was his dick. It all seems quaint in retrospect — the furor over a long shot of a boob on TV for less than a second. Hell, even the Super Bowl has decided to let bygones be bygones by inviting Timberlake back. (Jackson, notably, will not be there.)

But Nipplegate, as it was known, was more than one of those weird weeklong morning-show and gossip-magazine scandals that enter our brains through late-night monologues and bad jokes. It also played a pivotal role in internet history: It spawned YouTube. Site co-founder Jawed Karim “recalled the difficulty involved in finding and watching videos online of Jackson accidentally baring her breast during the Super Bowl show,” according to a 2006 report from USA Today. Like most advances in web infrastructure, YouTube was born from humanity’s demand for pictures of boobies.

It is easy — almost too easy, some might say — to post multimedia online now. By 2011, half its lifetime ago, Facebook had an archive of 140 billion photos; 10,000 times larger than the Library of Congress’s photo collection. About 65 years of video is now uploaded to YouTube every day. Before increased bandwidth and widespread broadband deployment, before the rise of social media as a cultural phenomenon, it was not that easy to put an image online, and it was almost impossible to find a web service willing to host a video for you for free.

Even the most cursory snapshot of the pre-YouTube web we had at the time of Nipplegate reveals an online space that we’ve quite literally lost. Dead hyperlinks and low-res images. If we get lucky, they might exist on the Internet Archive, but much of it is lost to time. Not even Google can help us recover them — as Tim Bray noted, anecdotal evidence suggests that the dominant search engine is no longer indexing the early web, likely because there’s little ad revenue to be gleaned from it.

It’s easy to find video of Nipplegate online now. But in the immediate, frenzied aftermath of Nipplegate, in the late night of February 1, 2004, and the morning and weeks after, how did everyone relive the controversy online?

Chief among the people I discovered riding the nipple-outrage wave was Matt Drudge, the proprietor of the Drudge Report. At 9:27 on the West Coast on the night of the performance, Drudge filed his first article, quoting a “well-placed source” who said that top network executives had approved the stunt. By the following afternoon, it had been updated with two images: a photo of Timberlake and Jackson, with her breast exposed, and a zoomed-in, blown-up image isolating Jackson’s areola. Directly below the images was the headline, “OUTRAGE AT CBS AFTER JANET BARES BREAST DURING DINNER HOUR.”

Poring over the 2004 Jackson coverage outside of professional media outlets reveals a web that feels handcrafted and bespoke. Examining the file names and directory paths shows a litany of deliberate choices. The close-up of Jackson’s nipple on Drudge is named “jjt.jpg.” It is a playful portmanteau of the initials J.J. and J.T., and completely useless for search-engine indexing. Another Drudge image from around the same period is named “jjteet1.jpg,” a rare triple portmanteau.

Instead of high-definition video and elaborate post-irony memes on Twitter, internet users in 2004 were treated to four-frame GIFs of Timberlake, with an animated penis Photoshopped onto his crotch, ripping Jackson’s blouse, hosted on sites like revengeworld.com (Archive.org link, NSFW, obviously).

Some old forum threads link to servers directly from their IP addresses, or to domains for long-dead hosting services. If you wanted to find video of the Nipplegate incident, you could, for instance, find it at 66.98.142.98/~volume/janet/JanetJustinHalftime-by_DaGlitch.avi or chaoshosting.net/janet_superbowl.avi. Chaoshosting! Of course!

The centralized platforms of the modern internet don’t have file names, they have identifiers — procedurally generated strings (youtube.com/watch?v=w5t-CmCwhZo) or a sitewide system of incrementing numbers (twitter.com/username/status/215908952024678400). The raw URL used to tell a story all its own, but no longer does. One discovery that hit me in a way that I cannot entirely articulate was the address mtv.com/onair/super_bowl/2004/flipbooks/half_time/images/boob.jpg because I’m imagining curious preteens crowded around a CRT monitor and one of them saying, “Go to em tee vee dot com slash on air slash super underscore bowl slash 2004 slash flip-books slash half underscore time slash images slash boob dot jay peg.”

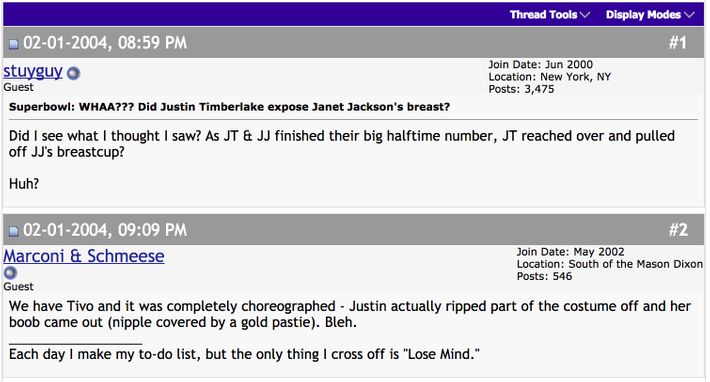

These URLs litter the web, collected not on Facebook and Reddit, but disparate forum threads scattered across different domains and hosts. There are threads on sports sites like dallas-mavs.com (“I saw that sucker flopping around and just about pooped my pants”) and therxforum.com, as well as sites like Fark, the Straight Dope, 12 Oz Prophet (“Who saw janet jacksons bood at the half time show I did, best part of the game”), Star Wars fan hub millenniumfalcon.com, and the Kawasaki-motorcycle-enthusiast board kawiforums.com. On Facebook now, groups coalesce around specific interests and often focus solely on that topic. On the decentralized web of old, a common interest in one topic gave way to discussion of many others.

The Kawasaki forum thread — “Janet Jackson’s Titty,” started at 4:37 a.m. on February 2, 2004 — features a link dump where the URLs speak volumes. There were, I’d infer, dedicated hubs for Jackson-boob pics at places like packetwarp.com/janetboobie or pornforlosers.com/janet or neotrinity.net/janet. Photos lived at URLs like speakeasy.org/~travan/WTFTIT.jpg (“Speakeasy,” in this case, is the name of a broadband ISP, not a secretive gathering place), and one member of the computer-science department at Montana State University hosted one of the clearest photos of Nipplegate at cs.montana.edu/~lindh/janet_closest.jpg. “LMAO!!! The very last link has quite the high-definition,” a subsequent poster wrote. “Anyone else notice how the pastie is being held on by a nipple piercing?”

The term link rot — when hyperlinks break permanently, usually due to changes on the link destination’s end — carries a negative connotation. That’s understandable, because as a civilization that generally prizes knowledge and information, the idea of losing those things is anathema. Clicking on a dead link and receiving nothing in response remains one of the most minor and most enduring frustrations of regular internet usage.

In contrast, megaplatforms and edge providers on the web must continually reckon with the vast stores of media and personal data that they keep live and accessible with a few clicks of a button. Tagged photos and status updates from a decade prior often haunt users now; it’s no surprise that Snapchat’s push toward privacy and ephemerality caught on. Instagram now allows users to archive posts, hiding them from other users, but not the profile owner. Earlier this week, ahead of new European privacy laws, Facebook made sure to clarify that when users delete things from their profile, Facebook deletes them from its servers as well. We are collectively relearning that not all information needs to be public and accessible in perpetuity. There are tiers of import when it comes to the stuff we post online. Inadvertently, it seems like the old web understood this better than the one we currently have.

It’s often said that “the internet never forgets,” yet when we look at link rot through the lens of Nipplegate, we see something else: a self-regulating organism that decides what is worth saving and what is not. Personally, I’m glad that most of the media-sharing links I uncovered were broken, or only accessible through the Internet Archive. Do we really need to maintain every single repository of a celebrity nip slip 14 years after the fact, especially in light of changing cultural norms around sex and decency? I’d argue that we don’t. It’s worth noting that Timberlake is getting another shot while Jackson unfairly received, by Timberlake’s own calculation, 90 percent of the blame. But through dead hyperlinks, we can still remember that these cultural fascinations did exist once upon a time, map markers to places that no longer exist.