The American people want big government to get its hands on their health care. Over the past two years, polls have consistently found overwhelming opposition to cutting federal health-care spending and broad, bipartisan support for increasing it. A majority of Republican voters believe that Paul Ryan should leave Medicaid and Medicare alone — while Uncle Sam should “ensure access to good health care.”

The ideological debate over whether every American is entitled to basic medical care, regardless of their ability to pay for it, is over. The Affordable Care Act succeeded in cementing the idea of health care as a right — while the law’s failure to arrest the steady growth in premiums and out-of-pocket costs has fueled public demand for further government intervention to secure that right.

On Thursday, Reuters-Ipsos released a poll that shows (what I believe to be) an unprecedented level of support for Medicare for All, the American left’s brand-name for a single-payer, national health-insurance plan. The survey found a whopping 70 percent support for the proposal, with 84.5 percent of Democrats — and 51 percent of Republicans — voicing their approval.

For the moment, this poll is an outlier (Medicare for All tends to poll well, but not this well). And there’s reason to think that the aberrantly high level of support it shows for socialized health insurance is a reflection of how nondescript the wording of Reuters’ question was; voters were asked whether they would support “a policy of Medicare for All,” but were not provided with any concrete definition of what that policy would entail.

By contrast, a March survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation asked voters “Do you favor or oppose having a national health plan, or Medicare for All, in which all Americans would get their insurance from a single government plan?” and found “only” 59 percent of respondents expressing support. Meanwhile, when Kaiser defined Medicare for All as a national health-insurance plan that is “open to anyone who wants it but people who currently have other coverage could keep what they have,” 75 percent of respondents endorsed the proposal — including 64 percent of Republican voters.

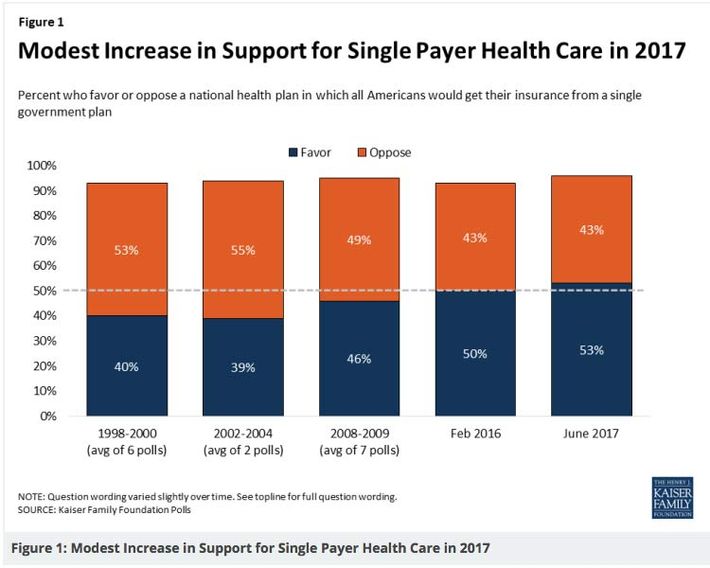

Previous polling from Kaiser has also suggested that both support for and opposition to single-payer are quite malleable. In June 2017, the pollster found 55 percent of voters approving of a single government health-insurance plan. But when Kaiser presented those who initially expressed support with right-wing counterarguments, 20 percent of respondents switched to opposing it; on the other hand, when those who initially opposed the idea were exposed to left-wing, pro-single-payer talking points, 17 percent came around to Bernie Sanders’s point of view.

Regardless, nearly 60 percent initial support is pretty darn good for a reform as radical as the elimination of the private health-insurance industry. And Kaiser’s surveys suggest that the policy has been (slowly but surely) gaining support over time.

These results — combined with the broader data showing a widespread consensus in favor of expanded government involvement in health care — suggest that the conventional wisdom (among mainstream commentators and Democratic consultants) has greatly overestimated the political risks of campaigning on Medicare for All, while underestimating the potential rewards.

But the politics of campaigning on single payer — and the politics of actually implementing it — are two very different things. And data showing broad support for Medicare for All in polls that provide voters with no specific information about the proposal’s implications for their tax bills, tell us less about the policy’s viability as a governing agenda than many progressives wish to believe. Once single-payer champions began trying to put taxpayer money where their mouths were in Colorado and Vermont, they proved unable to retain public’s support in the face of well-funded opposition. Even in deep blue California, a recent poll found that 53 percent of likely voters back single payer at first blush — but only 41 percent still do once they’re informed that the policy would require new taxes.

To win the fight at the federal level, single-payer advocates will need to weather a blitzkrieg of opposition messaging from every corner of the (profoundly deep-pocketed) health-care industry, and overcome the resistance of at least some risk-averse, ideologically moderate red-state Democrats in the Senate. Doing that will likely require mobilizing a massive, grassroots movement — and coming up with better, more specific answers for the policy’s skeptics.

Single-payer advocates do have a go-to response to tax concerns: “Don’t worry, all middle-class Americans will save more on health insurance than they’ll lose to the IRS.” But this argument lost the day in Colorado and Vermont; and, when applied to the most popular single-payer plans on the left today (i.e. Bernie Sanders’s), the claim probably isn’t true. As the health-care policy wonk (and single-payer supporter) Jon Walker recently explained:

[U]nderlying the whole message are some economic assumptions that can be tough for people to believe. The biggest is that, by ending a company’s need to provide health insurance, companies would raise their employees’ wages by how much they had previously been paying in premiums.

Even if that is true for many people over the long term, it will not be true for everyone, particularly in the short term…For instance, a company may choose to withhold these wages from employees who aren’t as valuable as they once were. There are also struggling companies that will do anything to cut costs they think the can get away with, even if it just delays the inevitable. This big benefit/tax transition would give those companies an opportunity to try to hide a pay cut while trying to stay afloat.

Similarly, any federal single-payer bill that effectively takes over Medicaid and pays for it with a new federal tax would free up states’ current Medicaid spending. To make sure everyone is roughly as well-off, states would need to use the savings for a broad income tax cut which mirrors current premium spending.

The federal government can’t make states do this, and since many states don’t have an income tax, it would be difficult even if they tried. Some states might use the savings to only cut taxes for the rich or to plug long-term budget holes, hoping voters will blame the federal government when they don’t “feel” the promised tax relief.

There are several different ways that progressives could mitigate the tax issue through policy design. The simplest of these would be to simply make single-payer much cheaper for taxpayers, by mandating drastic reductions in payment rates for pharmaceutical companies, doctors, and hospitals (something existing plans have largely sought to avoid). As Walker notes, specialist physicians in the U.S. make roughly three times what similar doctors earn in Sweden, and twice what those take home in France or the United Kingdom; and the average annual salary among American physicians has grown by nearly $100,000 in just last seven years. Our hospitals and drugmakers are similarly (if not more gratuitously) overpaid by international standards.

Given that the health-care industry’s interest groups are bound to loudly oppose any single-payer plan, regardless of its provisions on provider payments, it would probably make more political sense to force big pay cuts on providers than to force giant tax hikes on the entire middle class. And this would also make more policy sense, from both a technocratic and progressive perspective: Having the world’s most well-compensated hospitals, doctors, and drug companies means having a health-care system that regressively redistributes income from working-class Americans to affluent health-care professionals to a greater extent than any other nation’s.

(To be sure, any plan to impose a massive pay cut on American doctors would need to address the exorbitant costs of our medical schools, and also make it easier for foreign doctors to immigrate to the U.S., to ensure that slashing provider salaries doesn’t exacerbate the present shortage of primary-care doctors in our country.).

If progressives would rather avoid inflicting austerity on doctors and hospitals (i.e., the health-care industry’s most popular special interests), there are other approaches they could take to overcoming the political obstacles inherent to passing single payer, some of which Walker has outlined.

But all viable strategies will proceed from the recognition that getting Congress onboard with Medicare for All legislation will be far more difficult than getting voters onboard with Medicare for All as an abstract concept has proven to be.