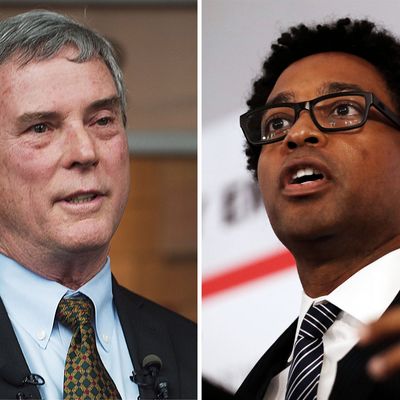

Bob McCulloch has been St. Louis County’s prosecuting attorney for 27 years. Through his seven terms in office, McCulloch has earned a reputation for upholding law and order by aggressively prosecuting alleged criminals — unless said criminals happen to be cops; in his entire tenure, McCulloch has never indicted a single police officer for killing an unarmed civilian in the line of duty.

That piece of McCulloch’s record garnered national attention in 2014, after Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson fatally shot 18-year-old African-American Michael Brown — and triggered a national Black Lives Matter movement. In that case, McCulloch made the unusual decision to empanel a grand jury to investigate the shooting, without recommending that said jury bring charges in the case. Instead, McCulloch presented the grand jury with a variety of evidence, and encouraged it to reach its own conclusion about whether the shooting qualified as a criminal act.

Few prosecutors have ever lost reelection for being perceived as excessively sympathetic to police officers, and insufficiently merciful to alleged offenders or disruptive protesters. But the ranks of such losers have been growing in recent years — and last night, McCulloch joined them.

Former public defender, and current Ferguson City Council member, Wesley Bell defeated McCulloch in a Democratic primary Tuesday night, after campaigning on pledges to appoint special prosecutors in police-shooting cases, end cash bail for low-level offenses, expand the county’s drug courts, provide more low-level drug offenders with alternatives to incarceration, and never pursue the death penalty in any case. McCulloch rejected these proposals, insisting that ending cash bail is unnecessary because “[t]here’s nobody in St. Louis County in jail being held on a misdemeanor because they can’t make bond.” The ACLU begs to differ.

Since no Republican will be on the ballot in November, Bell is now the county’s presumptive prosecutor-elect. And his victory is the latest triumph for a burgeoning movement that aims to reform America’s draconian criminal justice system, one prosecutor at a time. While much of the debate over mass incarceration has focused on Executive branch policies and congressional legislation, local prosecutors enjoy immense, unilateral authority to transform how criminal justice is defined and upheld within their jurisdictions. More than 90 percent of criminal convictions in the United States are secured through plea deals — which means, in almost all cases, prosecutors have the discretion to decide what sentence to seek for a given offense, and/or, what charge to assign to given criminal act. In practice, this has not redounded to defendants’ benefit. As Vox’s German Lopez notes:

Analyzing data from state judiciaries, John Pfaff, a criminal justice expert at Fordham University, compared the number of crimes, arrests, and prosecutions from 1994 to 2008. He found that reported violent and property crime fell, and arrests for almost all crimes also fell. But one thing went up: the number of felony cases filed in court.

Prosecutors were filing more charges even as crime and arrests dropped, throwing more people into the prison system. Prosecutors were driving mass incarceration.

Crime has fallen precipitously in recent decades — but the percentage of Americans believe that crime is rising has not. And since prosecutors are accountable to voters, public perceptions have carried more weight than reality: Conventional wisdom — and empirical evidence — has long suggested that throwing the book at offenders is politically wise, while showing leniency to the wrong offender (i.e., one who goes on to commit more serious crimes) is one of the few ways for incumbent prosecutors to lose their jobs.

But activists are beginning to change this calculus, particularly in big cities, where the combination of a large constituency for reform — and low-turnout municipal elections in which well-organized movements can prove decisive — has helped them elect a number of reformist prosecutors. Philadelphia district attorney Larry Krasner has already affected something like a law-enforcement revolution the City of Brotherly Love. As Maura Ewing has written for Slate:

Krasner’s lawyers are also now to decline charges for marijuana possession, no matter the weight, effectively decriminalizing possession of the drug in the city for all nonfederal cases. Sex workers will not be charged with prostitution unless they have more than two priors, in which case they’ll be diverted to a specialized court. Retail theft under $500 is no longer a misdemeanor in the eyes of Philly prosecutors, but a summary offense—the lowest possible criminal charge. And when ADAs give probation charges they are to opt for the lower end of the possible spectrum. “Criminological studies show that most violations of probation occur within the first 12 months,” the memo reads, “Assuming that a defendant is violation free for 12 months, any remaining probation is simply excess baggage requiring unnecessary expenditure of funds for supervision.”

Bell’s platform is less ambitious than Krasner’s. But his victory is nonetheless likely to reduce the number of St. Louis residents who sleep in cages because they are too poor to post bail — and persuade other local prosecutors that protecting violent cops, and imprisoning nonviolent offenders, isn’t the best way to improve their job security.