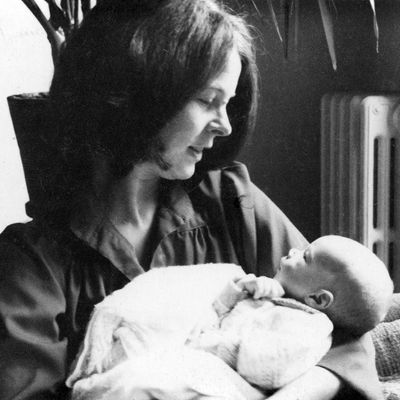

Elaine Pagels has made a career out of rewriting Christian history. Her first book, the 1979 best seller The Gnostic Gospels, reappraised Christian documents long considered heretical. In the books that followed, she took on the development of Satan, the apocalypse, and original sin, writing with academic rigor for a broad audience. Most of those books were informed by cataclysms in her personal life, as she outlines in her new memoir, Why Religion? In 1987, her 6-year-old son, Mark, died after a prolonged illness; the following year, her husband, the famous physicist Heinz Pagels, died after falling from a mountain in Colorado.

Why Religion? evokes the depth of her grief, but it also contains a twist: The scholar is also a believer — of sorts. In an increasingly pluralistic world, with the Catholic Church marred by scandals and Evangelicals compromising their values to support Trump, Pagels represents a religious contingent — less doctrinaire and more self-guided — that’s likely to keep growing. We met recently at her office at Princeton University, where she’s taught since 1982, to discuss how she’s tried to shore up the fragments of a religious life.

You’ve always written about the social history of texts, but now you’re doing that kind of excavation work on your own personal history.

One friend who’s a college professor said to me, “If you write this, they’ll think you’re not a scholar anymore.” That was a little unsettling, coming from someone I respect. But I can show you my CV. If people don’t think I’m a scholar, that’s not my problem.

Did it make you think about your work in a different way?

No — I was thinking about this all along. I just didn’t know I’d ever talk about it. The death of a child is one of the things that many people who have experienced it don’t talk about. People would more easily talk about their sex lives. But it feels liberating to open about something that was such a hidden part of one’s own experience.

The title has two meanings, right? You’re asking both, “Why does religion persist?” and also, “Why participate in religion?”

My late husband asked that question when we first met. He thought it was crazy that I was studying this. And he came to really enjoy the work — and I came to really enjoy his work. I loved to hear about elementary particle physics. It’s all analogies — black holes and string and glue. They think in images, and I do, too. I think imagining is what religious tradition is. It’s like poetry. A lot of it is poetry. But also, at first, as I wrote this, I was thinking, “What hit me when I went through that evangelical thing as a teenager?”

Your parents weren’t religious.

Well, sometimes my mother took me to a Methodist church. It was basically boring. And then my best friend — going to her Catholic church was really scary. That was about it. I was much more engaged with poetry and music and dance.

But then you ended up converting at one of Billy Graham’s events — not a service rich with poetry.

It was about living in a universe where there’s God and there’s Satan, and you’re part of this huge drama. I think that was very appealing in the early Christian movement, too. For me, it lasted for about a year and a half.

When you first encountered the secret gospels in grad school, what did you find so appealing about them?

I was told they were heresy, and that made them very attractive. The word “heresy” in Greek means “choice.” Also, no one had ever seen these books. So I opened up the Gospel of Thomas, and it said, “If you bring forward what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” I thought, “Hey, you don’t have to believe that — it just happens to be true.” It’s about creativity, or any kind of emotional or intellectual suppression.

If more people were to read them, how do you think it would change their understanding of Christianity?

What is known as Christianity today is a huge spectrum, from Russian Orthodox to Pentecostals, or Christian Scientists, or Quakers, or whoever. But it’s still a stream focused upon four particular views of Jesus and his message. Now we know it was once a much wider stream.

Could you talk about the experience you had when your son was dying?

I had always been brought up to think that when people die, as Steve Jobs once put it, “It’s lights out.” I was habituated to thinking about it in a scientific way. The experience of my son’s death was very different: I had a sense of other things happening that were mysterious, and I still don’t know what to make of them. I wouldn’t have even said it was his soul leaving the body, but there was — like, an energy or something. I sensed that somehow he was glad to be out of the body. It had been such a stress for him to stay in a body that was so challenged.

Things like that can’t be scientifically verified, but they happen. At one time I would have thought that it’s projection. And then when my husband died, the following year, what came into my head was totally alien to what I was feeling then: It was him saying, “This is fine with me.” It was not my unconscious speaking. It didn’t feel like it. It wasn’t reassuring. It was not fine with me; it’s not fine with me now. But that’s what came. I questioned whether to write about that stuff, because people may think I’m going off the deep end. But why not? People have these experiences all the time.

Was there a connection between your son’s death and the book you wrote afterward, about original sin?

I had read an article by some psychologist who said that whenever something is wrong with a child, the mother blames herself. The father does not. My husband was devastated, but he didn’t feel guilty. I did. So I had to realize that guilt is a kind of façade in such a situation for the worst thing — the sense that you’re completely helpless about what matters to you more than your life. So then, I was looking at how the culture teaches that human beings get sick and die because we sinned. “It’s your fault. It’s my fault. We’re all guilty.” This is a very peculiar point of view, but it is the way people have coped since the story of Adam and Eve.

Then I was reading an opponent of Saint Augustine, who created original sin. This opponent said, “Illness and death are just part of nature. They’re not punishments at all” — and that’s what I believe. My child had some illness. It happens all the time; it’s not about us. So these old stories became a kind of yoga, which let me play them out, explore them, turn them around, struggle with them, and come to different insights.

How has your own spiritual life changed over the years?

I didn’t go to any church for a long time, and then I did start to go when my son was diagnosed. I was running around Central Park and I was very cold, so I went into this church to get warm. It was a big Episcopal church at Central Park West and 92nd Street. I was really moved by this incredible music. There’s something about engaging the spiritual dimension in life that, for me, is essential. I don’t think it is for everybody. I mean, I have a close friend who does this in her work in theater. My husband was dealing with his way of understanding through physics and the natural world. But for me, there’s something very powerful about that kind of music. It’s not the only kind. I like the Grateful Dead.

The memoir describes a beautiful friendship you developed with some Trappist monks — Catholics — living in Colorado.

Yes, my husband and I were invited to go up to their monastery in Colorado, where we used to stay in the summers. They taught me how to meditate. I started going pretty much every week to a Thursday night Eucharist. They knew I was a heretic and a Protestant, but they always included me. It’s a very powerful place.

There’s an interesting contrast between their approach and yours. Yours is all about personal choice — what your friend called “Cafeteria Christianity.” The monks are deeply grounded in one tradition. Do you see any advantage in their approach?

I suppose — if you’re deeply grounded in it. You see this with Christian monks or Buddhist monks. In their presence, you feel it.

Not for you?

Not my style. Monasticism doesn’t appeal.

What do you believe?

One thing I believe is that we need to have hope. I don’t know what happens when we die, but I will hope that I’ll see those people again. Do I think so? I kind of don’t think so. But this is about how we live without being overwhelmed by depression. What I’m talking about is not on the level of thought as much as it is about intuition. I enjoy some of the pictures of it, like Blake’s paintings. There are wonderful spirituals that sing about it. Or the poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. One of my teachers used to say, “The minute after I read, ‘The world is charged with the grandeur of God,’ I’m in it for at least a minute.” It’s amazing that we go to churches and people bury people and say, “I am the resurrection and the life. Whosoever believeth in me will never die.” It’s so counter to what’s right there. But we do it.

Do you think that kind of religious expression is headed toward extinction?

Well, I was always told, “Yes, of course, it will die out as soon as everybody gets smart enough to realize about science.” And now I say, “This is much deeper than that.” I don’t think church attendance is much of an index. That’s why, at the end of the book, I wrote about this text which speaks of Jesus as the healer of hearts. People have as much need of healing of the heart as we ever have.