The late George Herbert Walker Bush was the patriarch of one of the more successful political dynasties in U.S. history, serving as president, siring another president, and then a second son who at one point looked on course to win the presidency. But “Poppy” (as he was known from childhood) Bush was also haunted by a problem that eventually felled him, frustrated George W. Bush and thwarted Jeb Bush: a struggle to keep step with a conservative ascendancy in his Republican Party that kept becoming more extreme and deeply mistrusted the family’s patrician origins.

Poppy followed in the footsteps of his politician father Prescott Bush, who represented Connecticut for a decade in the U.S. Senate. Prescott was by any measure a moderate — or even liberal — Republican: a despiser of Joseph McCarthy, a close friend of Nelson Rockefeller, and a supporter of civil rights legislation. Even more conspicuously, Poppy’s father was heavily involved in Planned Parenthood (and its predecessor organization, the Birth Control League), and the quintessentially WASP-y cause of family planning.

Prescott’s son, though, began his political career in the very different environment of Texas, where he had moved to get involved (successfully) in the oil business. In his first campaign, a 1964 Senate bid against liberal Democrat Ralph Yarborough, George H.W. Bush was skeptical of federal civil rights legislation. But he also fought John Birch Society efforts to dominate the GOP in Houston, and after being elected to the U.S. House in 1966, struck a more moderate pose. He also resumed his family’s mission in supporting Planned Parenthood, as Pema Levy recalled:

As a congressman from Texas from 1967 to 1971, the future president championed federal funding for groups including Planned Parenthood and access to family planning for all Americans. His dedication to the issue earned him the nickname “Rubbers.”

After another unsuccessful Senate race, Bush remained prominent in the moderate-to-conservative “establishment” wing of the national Republican Party. He was appointed by Richard Nixon as Ambassador to the United Nations at a time when no self-respecting ideological conservative would have come near that organization; then as chairman of the Republican National Committee; then as envoy to China, even as conservatives were still smarting over Nixon’s “betrayal” in recognizing Beijing. When Nixon’s successor Gerald Ford had to name his own vice president, Bush was reportedly the runner-up to his father’s old ally Nelson Rockefeller.

By the late 1970s, Poppy was ready to run for president himself, but had to accommodate himself to an increasingly conservative party. This meant trading his old devotion to family planning for an alliance with the anti-abortion movement, which had quickly become powerful in the GOP. Still, Bush’s lack of credibility with serious conservatives meant active resistance to plans in the Reagan camp to consider Bush (Reagan’s last surviving rival in the 1980 primaries) as a running-mate, which nearly culminated in a Reagan-Ford ticket (before talk of a “co-presidency” spooked Reagan’s advisors).

As Reagan’s vice president, of course, Bush abandoned all his non-conservative positions (including his devastating description of the supply-side tax-cutting mania as “voodoo economics”) and became so subordinate that when the time came for the veep to succeed Reagan, his biggest worry was what pundit’s called “the wimp factor.” And in a supremely ironic development, given his background, Bush’s initially troubled 1988 presidential campaign was rescued by hard-core conservatives such as anti-tax crusader Grover Norquist (who savaged chief rival Bob Dole for refusing to sign a no-new-taxes pledge) and Christian Right figures impressed at his loyalty to Reagan. The fact that Bush showed no squeamishness over the nasty racist tactics of advisors like Lee Atwater indicated that his patrician legacy was disposable.

But like his father and his sons, George H.W. Bush could not come to a comfortable place with an increasingly dogmatic conservative movement. His 1990 violation of his “no new taxes” pledge in order to reach the deficit reduction deal demanded by panicky stock markets undermined his conservative support in 1992, when his reelection looked momentarily vulnerable to a Pat Buchanan challenge, and he bled considerable support to independent candidate Ross Perot. He also ran afoul of conservatives when his first Supreme Court appointee, the obscure state jurist David Souter, turned out to be pro-choice and generally quite liberal; Bush’s effort to make up for that with his 1991 appointment of Clarence Thomas was an ideological concession of great import that nonetheless did not placate his critics on the right.

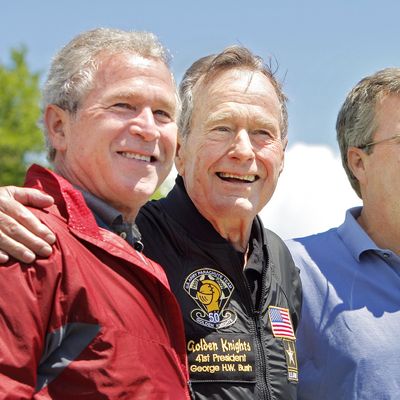

If Poppy’s two sons learned anything at all from their father’s experience, it was that establishing a conservative bona fides was critical to a successful career in modern Republican politics. They took two routes to the same goal. Jeb moved to Florida, abandoned the ancestral Episcopalian faith for Catholicism, and married a Latina, while projecting an image as a relatively cerebral ideologue. George W. doubled-down on his Texas background, cultivating an authentic accent, abandoning Episcopalianism for an evangelical-flavored Methodism, and becoming friends and allies with conservative power-brokers like Karl Rove. When both sons ran for governor in 1994, W. won while Jeb lost, which is how the former leap-frogged the latter in the dynastic pecking order.

By 2000, George W. Bush and his allies were letting it be known that while he was the biological son of George H.W. Bush, he was the ideological son of Ronald Reagan. And movement conservatives aligned with the Christian Right did indeed save his bacon when John McCain very nearly ended his presidential candidacy prematurely with a big win in New Hampshire. With an assist from conservative Supreme Court appointees, W. reclaimed the White House his father had lost; And after the tragedy of 9/11, his popularity shot up. With “boy genius” Rove guiding a domestic policy shop focused on building a durable GOP electoral majority, it looked for a bit like the family curse of fractious relations with conservatives had finally been lifted.

But after sticking with him through a tough 2004 reelection campaign, conservatives became progressively disillusioned with W.’s inept management of the Iraq War and homeland calamities like Hurricane Katrina, and with his pursuit of policy heresies like Medicare Part D and comprehensive immigration reform that Rove considered necessary to expand the party’s base. As Bush prepared to leave office, the financial sector exploded, the economy lurched into recession, and nobody much regretted his departure. His old rival McCain won the GOP nomination to succeed him, and Democrats won a landslide victory that seemed to usher in a post-conservative era.

But Barack Obama’s popularity waned too, and conservatives made a powerful comeback in 2010. As the 2012 election cycle began, there were calls (most notably from Rich Lowry, editor of the flagship conservative publication National Review) for Jeb Bush to at long last to make the move towards the White House he might have made twelve years earlier. Such calls were briefly echoed again when GOP front-runner Mitt Romney stumbled momentarily during the 2012 primaries. Jeb took a pass, but with Obama leaving office in 2016, the time had apparently come for the very true, very blue, True Conservative of the Bush family to harvest all those decades of efforts to win acceptance from the right.

And as we now know, despite vast resources and an immense number of endorsements, Jeb Bush was blown off the stage as the representative of mushy moderate elites out of touch with a new, savage mood in the GOP and the conservative movement, too. Poppy’s and W.’s internationalist credentials, which the Cold War vintage of conservatives deeply appreciated, were treated by conservatism’s dark new lord, Donald Trump, as signs of elitist contempt for America’s interests. Reversal of Rove’s big cause of immigration reform, thought necessary to pull Latinos into a GOP big tent, became job one for the nativists and white identity politicians led by Trump. And Jeb himself, far from being the exciting and hyper-competent ideologue who would finally burnish the Bush brand, became the “low energy” object of a hundred Trump jibes, and the epitome of tired and empty politics.

We don’t know what Poppy thought of the trajectory of the family project in politics in his final days. The only Bush family member now active in statewide politics, Jeb’s son George P., the Texas Land Commissioner, has made his peace with Trumpism even as the earlier generation of Bushes have kept a disrespectful distance from the 45th president. But it seems likely that the decades-long effort of this family to keep up with American conservatism has ended in exhausted defeat. Maybe there’s still room for some of them at Planned Parenthood.