On a day when the cold makes the skyline snap into focus as if you’re seeing it through new lenses, Hudson Yards seems more virtual than real. Jagged and reflective, the five new towers have a high-definition clarity that the physical world mostly lacks. At a distance, the tallest looks like a high-browed robotic duck with a beak so generous you could almost land a helicopter on it. That’s the outdoor observation deck, which juts out 65 feet and comes to a point 1,100 feet above the street. From here — or better yet, from the set of bleachers that allows you to peer over the glass railing — I can look down on the Empire State Building. I can behold the widescreen, high-res view of a New York more orderly and wondrous than the one most of us live in. The space won’t open for another year, but I can already see the over-the-top weddings in the party room upstairs, where guests can dance far, far above the stink and mess below. An adventurous few will be able to take a dedicated elevator even further up to the pointed peak, don a harness, climb out on a catwalk in the open air, and howl into the wind.

On March 15, after 12 years of planning and six of construction, the Related Companies (which is actually just one mammoth real-estate company) will open the gates to its new $25 billion enclave, an agglomeration of supertall office towers full of lawyers and hedge-funders, airborne eight-figure apartments, a 720,000-square-foot shopping zone, and a gaggle of star-chef restaurants. When the rest of it is finished — when the remaining rectangle of exposed rail yards between 11th and 12th Avenues is covered by a deck and more residential towers — the whole 28-acre shebang will be bigger than the United Nations, the World Trade Center, or Rockefeller Center and physically vaster, more populous, and more expensive than any private development in the country. Besides being big, Hudson Yards represents something fundamentally new to New York. It’s a one-shot, supersized virtual city-state, plugged into a global metropolis but crafted to the specifications of a single boss: Related’s chairman, Stephen Ross. (You can read about him here.)

Each time I approach, I feel a volatile mix of wonder and dejection roil in my chest. New York can absorb even this, I tell myself. Offices will hum with necessary invention, the plaza will teem, and the towers will settle into the accommodating skyline. The complex redeems an area that until recently most New Yorkers barely knew existed, a great pit full of resting trains open to the sky. There will be jobs, yogawear, art shows, tapas, even some affordable apartments. New York isn’t done building towers, and unlike the skinny plutocratvilles going up on 57th Street, new office buildings are a necessity, one where tens of thousands of New Yorkers will spend their days (and some will work through the night). Who’s to cavil when the money flows? The asset-management team BlackRock signed up to spend $1.25 billion in rent over 20 years. The retail complex will have at least six places where you can spend five figures on a wristwatch (Patek Philippe, Rolex, Cartier, Watches of Switzerland, Piaget, Tiffany). The 101st-floor party space, surely to be among the priciest available, will be the place to host the most ostentatious vodka launch in town. They’ve paved a parking lot and put up a high-rise paradise.

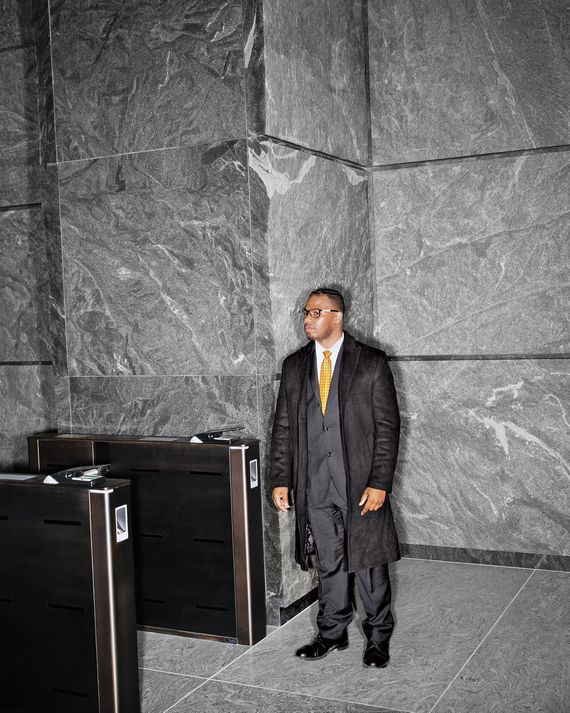

Yet I can’t help feeling like an alien here, as though I’ve crossed from real New York, with all its jangling mess, into a movie studio’s back-lot version. Everything is too clean, too flat, too art-directed. This para-Manhattan, raised on a platform and tethered to the real thing by one subway line, has no history, no holdover greasy spoons, no pockets of blight or resident eccentrics — no memories at all. In the renderings that Related uses to market this new world, just about every one of the digital people strolling through the virtual cityscape is young, thin, able-bodied, and white. It strikes me as profoundly strange, this need to re-create an uncitylike city, so aloof from the porous, welcoming, spontaneous metropolis we like to think we inhabit. The suburbs have become more mixed, trafficky, crime-ridden, and complicated, and so, if you need exclusivity at all costs, an urban enclave with a quick elevator ride to the stratosphere looks especially appealing. I suppose this apotheosis of blank-slate affluence is someone’s fantasy of the 21st-century city, but it isn’t mine.

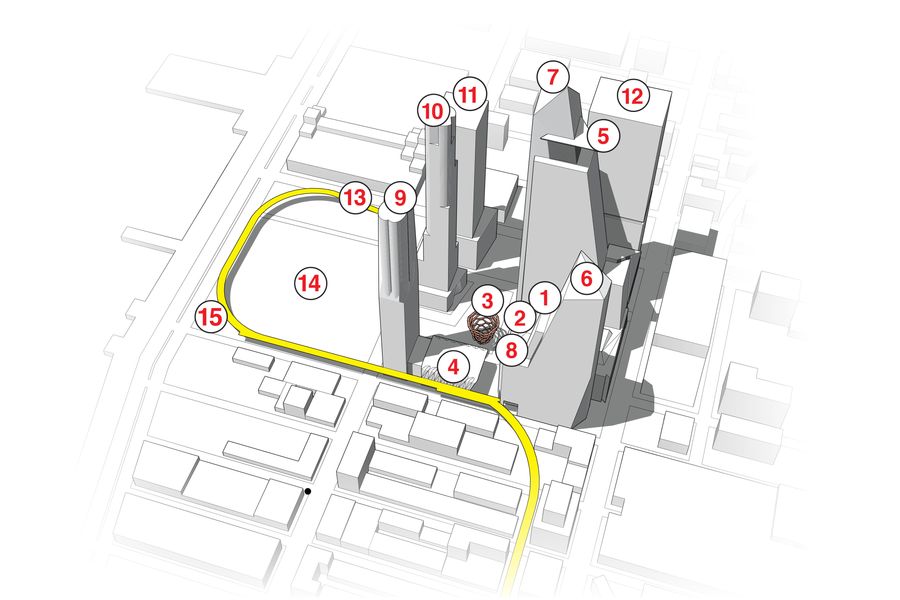

Again and again, I have wondered who wanted it to be like this, and when it became a foregone outcome. We’ve been headed here for a long time, as the city has become more moneyed and the only retail stores that seem sustainable are those of luxury labels. A crowd of gifted architects worked hard to figure out how gargantuan buildings and cliffs of glass could form a place — a stretch of city where human beings feel like they belong. Kohn Pedersen Fox designed 10 and 30 Hudson Yards, the faceted, shingled-glass skyscrapers flanking their shopping mall, with interiors by Elkus Manfredi. Diller Scofidio + Renfro and the Rockwell Group designed the tubular apartment building at 15 Hudson Yards and its conjoined performance venue, the Shed. Two more towers, 55 by KPF with Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates, and 35, an office-hotel-residential combo by David Childs and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, loom over the plaza by Nelson Byrd Woltz and a bucket-shaped latticelike objet by Thomas Heatherwick that is, for now, called the Vessel. Separately, these architects — most of them, anyway — came up with sensitive and sophisticated designs. Together, they created the opposite of their intention. Instead of an organic extension of the midtown fabric, they produced a corporate city-state, branded from sidewalk to spire.

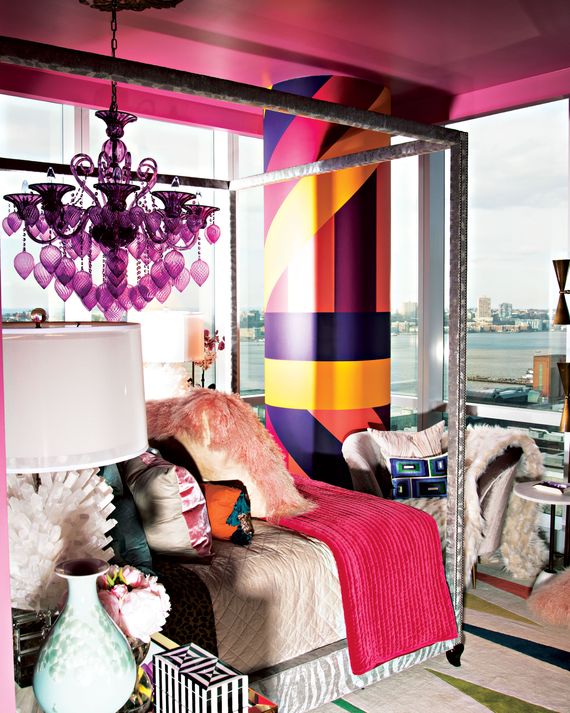

That brand is perfectionism. At a time when the most ordinary aspects of urban living, like taking the subway or steering past trash bags piled on the sidewalk, are so many frustration bombs lying in wait, Related promises a nuisance-free zone. Snow will not be permitted to accumulate on the sidewalks or humans to sleep in doorways. Door handles will be obliged to gleam at all times. If you wonder whether a real-estate company can be trusted to maintain those standards, consider that Ross himself is moving to a penthouse in his new fiefdom, and so is another top Related executive, Jeff Blau, the CEO. The company they run is coming with them too.

I’ve visited the construction site several times, and circled it many more, watching the towers lumber toward the sky and this improbable mirage take shape. Now, as workers rush to lay the final paving stones and finish wiring the lights, I tour it with Jay Cross, the project’s hands-on chief. I am in awe of the sheer managerial omniscience that allows Cross to grasp, predict, and control every aspect of construction, from the colossal to the picayune. Even if the whole East Coast goes dark, he tells me, the site’s co-generation plant will kick in within milliseconds, so that multimillion-dollar electronic transactions can continue whizzing around the globe without a hiccup. When the rains come and the waters rise, submarine doors will close around elevator machinery and fuel tanks. This shining city on a deck is built to withstand a wide range of plagues.

Cross is equally caught up in surfaces. He shows me the curved, Italian-made tracks for the elevator that snake up inside Heatherwick’s interwoven collection of staircases. He points out the custom steel joints sleek enough to be abstract sculptures, lighting strips embedded in handrails, pavers arranged in a mosaic of different grays. Architecture is composed of such minutiae, and, in a way, it’s reassuring to see a control-freak client at work, demanding equal levels of obsessiveness from a varied team of architects. As we walk through the lobby of 30 Hudson Yards, Cross reels off a list of sumptuous finishes as though he’s reciting the specials at an exotically unaffordable restaurant: fumed larch, book-matched Ombra di Caravaggio marble (smoky gray with ocher veins), a spritz of limestone, and bronzed aluminum. (Or is it anodized branzino? I forget.) The wavy walls of the lobby coffee shop appear to be clad in melted chocolate.

Ross wants his tenants to feel as though they occupy the best building in the best neighborhood in the best borough of the greatest city in the world. The bestness is all. Still, this is a privatized idyll, where the concept of public good stops at the property line. West 31st and 32nd Streets dead-end at the shopping mall’s forbidding wall along Tenth Avenue. When an architect agitated for a more lavish cladding, a Related executive waved him away. “Who’s going to see it?” he asked. For the developers, the towers gather round a central stage. The rest of the city is its back-of-house.

In this West Side Westworld, every aspect of the experience is curated by an unseen hand. Everything is engineered to suck passersby onto the property and keep them there, spending money, as long as possible. There are no storefronts in this version of New York, only indoor pathways through the seven-story shopping center. Visitors can browse at Van Cleef & Arpels as they wait for their table at Thomas Keller’s TAK Room or their time slot on the observation deck. For many office workers, the shortest distance from subway to desk leads past Tiffany.

It’s possible to live a full and varied life here — to sleep, put in an hour at the gym, bring the kids to school, drop the dog off at day care, go to the office, shop, eat out, visit a museum, and catch a show — without so much as crossing the street. That kind of total-service completeness has been a goal of smart-growth urbanists for many years, but it’s one thing to apply those aspirations to a semi-citified development around a suburban transit station, in the hope that it won’t go dead after rush hour. It’s a very different, and more disquieting, achievement to create a high-rise district on a plinth so sealed-off and yachtlike that nobody need ever leave.

There’s nothing new about the idea of a blank-slate city. The Romans built their gridded garrisons at the edges of the empire. Chandigarh and Brasilia were designed as complete capitals. Our own Rockefeller Center is an obvious predecessor. In the past few decades, advances in engineering and logistics, combined with a worldwide market for offices and high-end residences, have given real-estate companies and bureaucracies the ability to plan, finance, link, build, and populate tens of millions of square feet all at once. Hudson Yards may stand out in New York, but it fits right into a global context where new cities and urban enclaves come on line with frightening rapidity and, at the same time, authorities set aside multidecade, multibillion-dollar budgets to urbanize on an ever larger scale.

Starting in the 1980s, 97 acres of deteriorating London Docklands metamorphosed into the office district of Canary Wharf, linked to the rest of the city by ferry and light rail (and eventually by the Crossrail commuter train). The closest precedent to Hudson Yards is Tokyo’s 28-acre Roppongi Hills, which was developed by the Stephen Ross of Japan, Minoru Mori, and opened in 2003. It took Mori 17 years to assemble the parcels in the heart of Tokyo; Related slurped up its rail yards in a single gulp. In Abu Dhabi, Foster + Partners designed Masdar City as the zero-carbon metropolis of the future, and though the tens of thousands of residents it was designed for haven’t shown up, leaving the showcase area looking prematurely ghostly, it has turned out to be more of a lab and exhibition center for such purportedly planet-saving technologies as automatic shuttle buses and plant-based jet fuel. And all of those ambitions look puny next to the Chinese government’s plan for Jing-Jin-Ji, a metropolitan area larger than New England, which would swallow Beijing and have a projected population of 130 million.

After World War II, architects, planners, and politicians came to a consensus on the need to house the poor in modern, hygienic housing and to construct expansive campuses for education and the arts. Those projects came bundled with blind spots and racial prejudice, but they were powered by a kind of democratic idealism. The great promise of Hudson Yards was that a whole new zone of the postindustrial metropolis could be manufactured from scratch without the burdens of a messy past. There were no residents to displace, no favorite bookstores to bulldoze or preservationists to placate. Here was a chance to dream up the metropolis of the future afresh. But the political climate and economic imperatives short-circuited those fantasies and we got a bloated simulacrum instead. That failure to learn from past blunders, or to strive for a more equitable and humane city, constitutes a massive institutionalized failure of imagination decades in the making.

In 1974, the West Side’s outer edge was occupied by a largely dormant, two-mile-long train yard headed for liquidation by the bankrupt Penn Central Railroad. But nobody wanted it. Trains still had to keep running through at least part of the area, so the only way to turn it into buildable acreage was to cover it with a gigantic, prohibitively expensive platform. One person expressed an interest and took out an option to buy the land: the son of a Queens-based builder of middle-class apartments. Donald J. Trump eventually let that option lapse and brokered the state’s purchase of land for a convention center, offering to forgo his fee and build it at cost if he could name it … you guessed it, the Trump Center. The state said no and named it after Senator Jacob Javits instead.

Midtown has been pushing west toward the river since the 1950s, but without a platform atop them, the yards stood in the way of the city’s insatiable need for more residences, more businesses, more cubicles, and more places to eat lunch. The hollers got louder in June 2001, when a panel convened by Senator Chuck Schumer calculated that the city would need to build 60 million square feet of new office space in the coming decades to compete with fast-moving global centers like London and Hong Kong. Three months later, terrorists brought down the World Trade Center, wiping out another 13 million square feet.

Soon after Michael Bloomberg took office as mayor, in January 2002, his deputy Daniel Doctoroff revived his dormant fantasy of landing the Olympic Games. To get them, New York needed a new stadium, and Doctoroff calculated that putting it on the Far West Side could lure the Jets back to the city, serve as an expansion for the chronically cramped Javits Center, and stimulate that elusive burst of development. In pursuit of that vision, the city rezoned not just the rail yards but a much vaster area, from 30th to 43rd Streets, west of Eighth Avenue. It also raised $2.4 billion to extend the No. 7 line. The Far West was this new city’s most promising frontier because, at least in the popular imagination, there was nothing there. Colonizing that unwelcoming terrain meant overwhelming it with skyscrapers — lots of them. “The key question was: How much could you accommodate?” Doctoroff recalls.

From the vantage point of 2019, it seems as though New York has been on a three-decade binge of growth, gentrification, and ever-rising real-estate prices. But 17 years ago, Bloomberg and his lieutenants were haunted by its fragility, the terrible ease with which it could sink back into 1970s-style dysfunction. To them, cities were like sharks: They could decline or grow but never stay still. And as veterans of the business world, they shared an ingrained belief in the superior efficiency of private companies. “The private sector knows best how to build and how to make money. If at all possible, what we [government] should do is get out of the way,” said Mayor Ed Koch in 1987, and nearly 20 years later, Bloomberg and Doctoroff agreed. Manhattan, they thought, should be capitalism’s most spectacular creation.

In the end, the stadium idea and the Olympic dream both died, but not before opening the door to development on a Babylonian scale. With politicians and editorialists focused on the stadium, the city quietly rezoned the West Side for a city the size of downtown Seattle.

Meanwhile, Bloomberg hammered out a deal. The MTA, which owned the yards, wanted as much money as it could get and had no interest in building anything. The city brokered the sale of development rights, which Tishman Speyer won. But the sale fell through, and Related quickly stepped in with $1 billion. A few months later, the financial crisis pummeled the world and developers everywhere hunted frantically for rocks to climb under. Related held firm.

Doctoroff, now CEO of the urban tech company Sidewalk Labs, looks approvingly out at the site from his office at 10 Hudson Yards. “It’s in a long line of great spaces that will define this city, consistent with what we envisioned,” he says. “The basic principles haven’t changed.”

There is no more virgin territory in New York, no vast tract that can be bulldozed by fiat. Instead there is the air above dirty and complicated installations. At the West Side yards, train traffic could never be shut down during construction, columns had to be threaded among the tracks, prodigious amounts of heat had to be vented, and preparations had to be made for the Gateway Tunnel under the Hudson, just in case the federal government ever decides to fund it. Since there was nowhere to bury all the ugly, bulky hardware (sewage pipes, foundations, water mains), it all had to be packed into the seven-foot depth of a platform jacked up 25 feet or so above the Earth. Hudson Yards is a garden of levitating towers. To the Bloomberg administration, it was clear that only a major developer could raise the capital and cope with the technical challenges to get the project done.

“We got really lucky that Steve Ross had a passion for this,” Doctoroff says. “He had an organization that was capable of executing it on every level, from the engineering to the marketing. Related was probably the only developer in the world that could have pulled this off.”

Architecture, like politics and war, springs from a million separate decisions made within the context of vast historical forces, decisions that can seem freer or more meaningful than they really are. At Hudson Yards, the path to the ribbon-cutting followed an inexorable trajectory based on impregnable financial logic. Underutilized space must be reclaimed for its highest and best use. The MTA needed cash. Costs were high, so potential profits had to be too. The most efficient way to finance and engineer the project was to hand it off to a single developer, who was only ever going to build a city as a luxury product. Each decision made the next one essentially foreordained.

At times, that relentless march of circumstance can produce results that look insane or visionary, depending on the month. Conceived in the wake of the 2008 recession and executed during the boom that followed, the megadevelopment opens onto a troubling future. The market for ultradeluxe condos is sagging, and we’ll see whether that’s one of the shocks that Hudson Yards is built to withstand. A dozen years ago, it seemed obvious that retail would prop up a shaky market for office space. Now the opposite is true. The 720,000-square-foot mall comes online even as storefronts are shuttering all over New York and Amazon threatens the whole concept of entering a shop with money and walking out with a shopping bag. On the other hand, businesses that were once squeamish about relocating to an uncertain frontier zone are now gobbling up square footage. Companies like Coach, L’Oréal, Warner Media, Wells Fargo, and Boston Consulting Group will cohabit with creations of the millennial boom like Stonepeak, and the demand for office space seems likely to outpace the current glut.

All those vicissitudes and contingencies don’t matter much to the buildings once they’re up. The confluence of history, politics, and money has yielded an acropolis of global capitalism, an elevated monumental complex that will endure long after the faith has been forgotten.

Walk down most Manhattan avenues and your eyes rarely drift up beyond the first couple of stories; it is entirely possible to stride right past the Empire State Building and hardly notice it’s there. Hudson Yards confronts you with its ostentatious verticality. That’s because the plaza allows you the room to step back and look up toward the O of sky outlined by the towers’ tips. To temper that repetitive upward thrust, Ross demanded that the architects he hired forge a cogent composition out of disparate designs.

The problem is that each project has a separate set of ironclad givens and follows its own internal logic. William Pedersen, the co-founder of KPF, and Marianne Kwok, one of the firm’s directors, sit me down at a conference table with a scale model of Hudson Yards and make it clear that the glass façades, the massive floor plates, the distance from window to elevator core, and the resulting form all flow directly from the tenants’ needs.

Still, there’s a community to build. “Tall buildings look like a bunch of people standing around a cocktail party. Everything we do is about creating gestures of connection,” Pedersen says. And so his firm nudged two of those isolated hulks, Nos. 10 and 30, into a relationship of sorts. They angle in opposite directions, as if facing off at arms’ length in a stately tango. In its eagerness to communicate, the shorter of the pair, 10 Hudson Yards, gesticulates hectically in all directions. It’s an à-la-carte structure dictated by the varying desires of tenants: a huge floor plate for one, a more modest floor plate for another, a separate campus-within-a-building for Coach, views all around. At its base, the building ducks and dodges at its chamfered corner as if to avoid being tagged out. It leaps out of the way of the High Line, which swings beneath it toward the soon-to-open Spur. At the corner of Tenth Avenue and 30th Street, the atrium sucks in its belly to leave room for a plaza out front. The result is a skyscraper that looks as though it were welded together from chunks of other skyscrapers.

Pedersen and Kwok went to enormous lengths to root their architecture in the borough and, on those blocks, to continue a lifelong concern with helping towers “become social participants in the life of cities,” as Pedersen puts it. And yet, in the end, their designs are more profoundly shaped by larger forces: the overwhelming need to make New York a node along the migratory routes of money. Reflective, slope-walled, fat-bottomed towers like KPF’s are the physical traces of a worldwide electronic economy.

Whether the development feels more like a high-rise island or a continuous patch of Manhattan will largely depend on the parts where there are no buildings at all. More than half the site is public space — or, to be precise, privately owned public space (POPS), the kind of hybrid that feels utterly open and democratic until a private security guard informs you that you’ve just violated one of the owner’s policies. As soon as the landscape-architecture firm Nelson Byrd Woltz got the job of stitching a bunch of glass hulks together, its leader, Thomas Woltz, began quietly resisting the rigid geometries, inhuman scale, perpetual shadows, hard surfaces, and self-absorption. He has made the most of his minimal set of tools: pavers, plants, walls, and benches. From above — the restaurant terraces, say — the pavers form a series of variously shaped ellipses in degrees of gray, swooping like electrons around a nucleus. On one side, a dense mini-forest borders on West 33rd Street. On the other, parallel rows of black-gum trees, their branches sticking straight out from the trunk as if they were doing calisthenics, line up along gently arcing granite terraces. (Just to make sure they would perform as advertised, Ross insisted that Woltz take him on a tree-sighting safari around New York.)

The slope, curves, steps, and benches, the canopy of trees and woodland undergrowth, all mitigate the site’s diamond-edged immensity. “The pavement will be perfect. The benches will be clean. The trash will be picked up. But the plantings add up to a layered forest from ground cover to canopy, an exuberant horticulture that’s thick and full and rich. That’s a nice counterpoint to the tightness of the rest of the site,” he says. Still, he acknowledges, “there’s only so much a 50-foot tree can do to soften a 1,200-foot building. So I focus on the dialogue between the person and the tree — the human space beneath a horticultural ceiling.”

It’s an artificial kind of nature Woltz has fashioned, a highly engineered landscape on a seven-foot-thick platform. Since the trains below exhale a tree-killing heat, he got engineers from Arup to design a cooling system that would keep the meticulously formulated soil at a steady 70 degrees. The plantings have to withstand near-constant shade from the behemoths all around. Woltz aims to create delight within these extreme constraints. “I hope the public loves it. I hope they feel, This is for you, folks. It’s well crafted and well maintained and there’s plenty of room for everyone to have a seat and enjoy.” It will be months before he can know whether his wish has come true; no park should be forced to make a winter debut, as this one has been.

And no park should be forced to share its debut with the development’s preposterous centerpiece, an Instagram-ready tchotchke, 15 stories high and, at $200 million, as costly as a regional hospital. Heatherwick’s Vessel mushrooms up and out over the central plaza, inviting visitors to climb it, watch others climb it, or take an elevator up to a landing, then come back down. The advance hype doesn’t prepare you for a structure quite this large, shiny, and extravagantly pointless. Its stainless-steel skin gleams russet like polished copper but won’t weather or lose its gloss. From the beginning, Ross declared his desire for an artwork big and splashy enough to focus the whole development. Not a clock or an obelisk — how about a botanical puppy, say, or a Chicago-style shiny kidney bean? Ross wanted something bolder, an artwork he wouldn’t have to warn people off of. Instead, Heatherwick’s piece functions as its own sign: PLEASE CLIMB ON THE SCULPTURE.

Stairs can be social spaces. The architects of the Metropolitan Museum and the New York Public Library lifted those institutions above Fifth Avenue by means of imposing, processional staircases, but the city’s democratic culture eventually appropriated them as hangouts. Visitors use them to roost and recover. Even in winter there’s always a scattering of hardy types flaunting their endurance by seeing how long they can relax. In the past couple of decades, New York has become a city of sittable stairs: the scarlet staircase at Times Square, which functions as both stage and parquet, the lounging bleachers in front of Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, atop Pier 17, or at the water’s edge in Brooklyn Bridge Park. But Heatherwick’s honeycomb doesn’t really allow for loitering, only a steady trudge up, down, or all around. In disdainful compliance with the law, elevators deposit visitors with disabilities on a landing, where they can take a look but have nowhere else to go except back down. In theory the weave of 154 staircases and 80 landings offers thousands of possible routes, but in practice they are all endlessly the same, like the ramparts in Escher’s hermetic guard tower. You’ll need a timed ticket to go up. The Vessel embodies the aesthetic of hucksterism: It’s a staircase that takes you nowhere, clad in fake copper that never gets old, taking over a public space that’s actually private.

Ross has said he wants his Basket o’ Staircases to be New York’s Eiffel Tower or Gateway Arch (he used to compare it to the Trevi Fountain), and he is no doubt brimming with magnanimous feeling. “No one has ever given a gift like this,” he crowed to Fortune in 2016. He may be right. There are not many opportunities to erect such a grotesque monument to a rich man’s vanity.

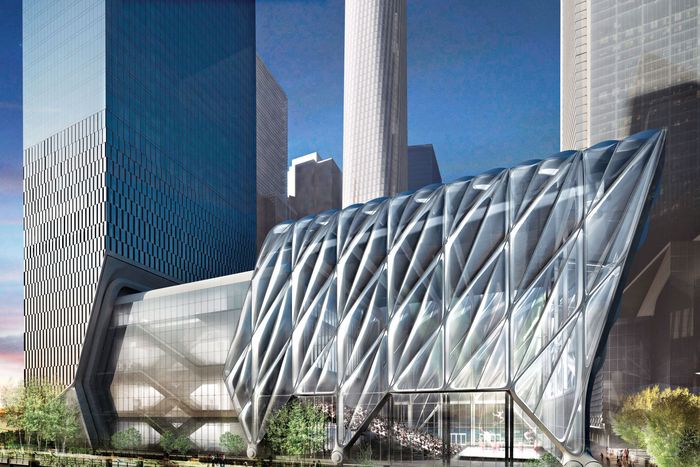

There is one grain of unpredictability in Related’s grand oyster, one hope for humanism at Hudson Yards: the Shed, a lavishly funded but endearingly weird headquarters of interdisciplinary art. When the city zoned the site, it held back one spot on the platform for a cultural building to be placed right on 30th Street, where the High Line jogs out toward the Hudson. Bloomberg wanted a new organization that would add to the cultural life of the city, not just move it around. The architects Elizabeth Diller and David Rockwell, leaders of separate firms, came up with both the idea for the institution and the building’s design. A packed stack of galleries, theaters, and performance spaces slips into the base of a residential high-rise, making efficient use of all those unsaleable lower floors. It’s not an easeful relationship. At the tower’s base a great steel mouth gapes, as if to swallow (or regurgitate) the icy cube of the Shed. A puffy, quilted sheath slides over that glass-walled core like a box made of Bubble Wrap. Depending on the event, the outer layer can either be tucked away against the tower or roll out on great steel wheels to enclose a square of the plaza. The space will open April 5 with a five-night multi-genre spectacle surveying the history of African-American music, curated by Quincy Jones and directed by Steve McQueen. Whatever else it achieves, the Shed will draw audiences and artists who might otherwise never go near Hudson Yards.

Bloomberg’s aspirations, Diller and Rockwell’s design, and Related’s priorities fit together with startling neatness. From a developer’s point of view, the Shed is a unique amenity, a museum–cum–concert venue steps from your office or kitchen. The more distinctive its productions, the better the bragging rights. At the same time, though, contemporary arts institutions, unlike real-estate developers, have a high tolerance for failure and unpredictability. The Shed will defy Ross’s craving for control and good taste, because artists can be loud, confrontational, vulgar, and crusading — all fine local qualities that clash with the Related brand. In the end, the Shed may turn out to be New York’s embassy to the principality of Hudson Yards.

In my more dyspeptic moments, I wonder what Hudson Yards portends for New York’s future. Today it feels like the last spasm of the Bloomberg era, seductive and smooth and substantial, the home of some finely provocative art but fundamentally a grand gift of urban space to the global elite. Will it become a bastion of a Gilded Age that has already started to wane or the unavoidable model for the next megadevelopment and the one after that? Already the city keeps ratcheting up its scale. Today’s supertall towers are being overtaken by even bigger ones. Lessons learned at Hudson Yards, if any, will be applied at Sunnyside Yard, which is seven times the size. These thoughts lead to darker questions: Is New York ballooning into oblivion? If you don’t know how to code or what private equity actually is, does that mean your choices are panic, despair, or flight? These musings seem almost reasonable when the new skyline glowers overhead. But then my mind drifts back to the alien separateness of Hudson Yards, and it occurs to me that could be its saving grace. Those who feel pushed away by it will never go there. It will keep hovering 25 feet above the street, a spaceship that hasn’t committed to landing, while the rest of the city scrambles on, peculiar and perpetually discontented, sending its chorus of sirens and grumbles up to the party on the 101st floor.

The Tech Beneath the Bling

No garbage trucks

In the (forthcoming) western section of Hudson Yards, the trash from the apartment buildings will be piped out through three separate chutes at 45 mph. It’ll be ground and dehydrated along the way, ending up at a dispensary on 12th Avenue.

Chilled roots

The trains running under the platform generate heat, and it can get up to 150 degrees down below. So the deck is filled with pipes that circulate cool water under the trees to keep them from being cooked.

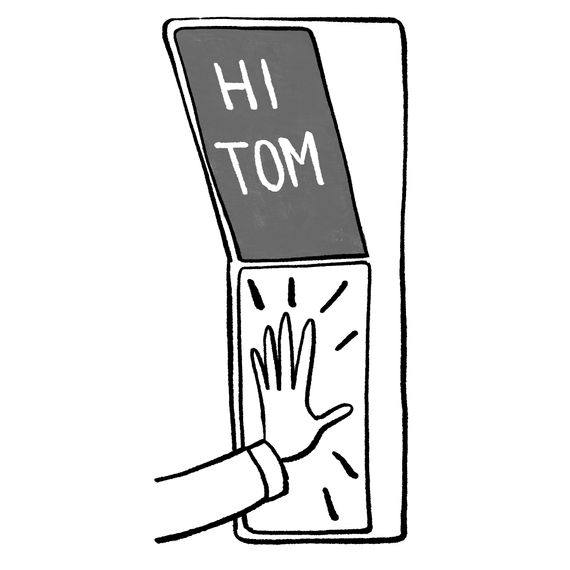

Its own comms network

Usually, your emails and calls go out on a network to your service provider — Verizon or whomever — and then back to your building. Here, there’s a private loop of fiber, embedded in the platform under the buildings and connecting them all, that makes internal communications much faster.

Its own power supply

The co-generation plants (there are two) make electricity with a generator, run on natural gas, whose waste heat is recaptured and used in the climate-control system. “If the entire Eastern Seaboard goes down, you can plug in your phone at Hudson Yards,” says Joanna Rose, Related’s executive vice-president of corporate affairs.

“Futureproofing”

A tech stack — the framework for software, living in the cloud and supporting different systems such as elevators and cameras — stores all of Hudson Yards’ data in one place. When “all these new sensors that come into the market, driverless vehicles, drone delivery services, all kinds of stuff, we’re going to be more easily able to accommodate,” explains Hudson Yards’ Luke Falk.

Of course, there’s an app

Residents can book a party room, buy tickets to the observation deck, or make restaurant reservations.

—Jane Drinkard

This Man and His Investor Friends Bought Seven Apartments at 15 Hudson Yards. We Asked Him Why.

Tony Salamé is a shopping-center developer from Beirut who has become one of the world’s biggest art collectors.

“When I first saw the Hudson Yards project, I told [Steve Ross’s partner] Ken Himmel I wanted to buy seven apartments. At first he thought I was joking, but I made an appointment with Steve the next day. He gave me and my friends a great deal, and we immediately blocked seven apartments on the 80th floor, one of the highest levels. It’s not only a building — it’s a whole community, with stores and amenities, and a short walk takes me directly to all the art galleries in Chelsea.

“What I like about Steve is that he’s a quick decision-maker. He often says to me, ‘Why did I get myself into this again?’ but he’s reinventing New York’s urban landscape. I’m extremely excited to move in.”

—Carl Swanson

*This article appears in the February 18, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!